"I see the downsides of AI, I see the problems for democracies [...] but at the same time, as an artist taking this as a reality, it is something I just love doing."—Boris Eldagsen, in our interview on his winning (and refusing) a prize for his AI-generated art at the SWPA.

Let Me Fall Again A review of Julia Borissova's photobook Let Me Fall Again

Falling holds a terrible allure. As children, we fall again and again, and learn how to pick ourselves up, lickety-split. As adults, however, we’re just so tired. With each fall, we accumulate bruising, callousing, and a sense of caution meant to save us from ourselves. Over a lifetime of falling—falling down, falling in and out of love, falling from grace, falling for lies, endless falls—we know both the pleasure of flight and the trauma of landing. Within each ‘leap into the void’ stirs the question: will I fly, will I fall wounded, or will this be my last?

Then, there are those who choose to leap.

In her most recent photobook, Let Me Fall Again, Russian photographer and bookmaker Julia Borissova presents a part-factual, part-imagined construction of the life of Charles Leroux, a professional jumper. Leroux was born in 1856 in Waterbury, Connecticut, and travelled the world to leap from great heights with balloons and parachutes for the benefit of an audience. He made 239 jumps in his lifetime before he died at the age of 32 during a jump in Tallinn, Estonia. I’m tempted to write “during a failed jump,” but what do I know?

In her most recent photobook, Let Me Fall Again, Russian photographer and bookmaker Julia Borissova presents a part-factual, part-imagined construction of the life of Charles Leroux, a professional jumper. Leroux was born in 1856 in Waterbury, Connecticut, and travelled the world to leap from great heights with balloons and parachutes for the benefit of an audience. He made 239 jumps in his lifetime before he died at the age of 32 during a jump in Tallinn, Estonia. I’m tempted to write “during a failed jump,” but what do I know?

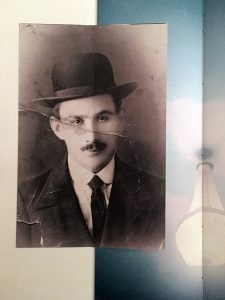

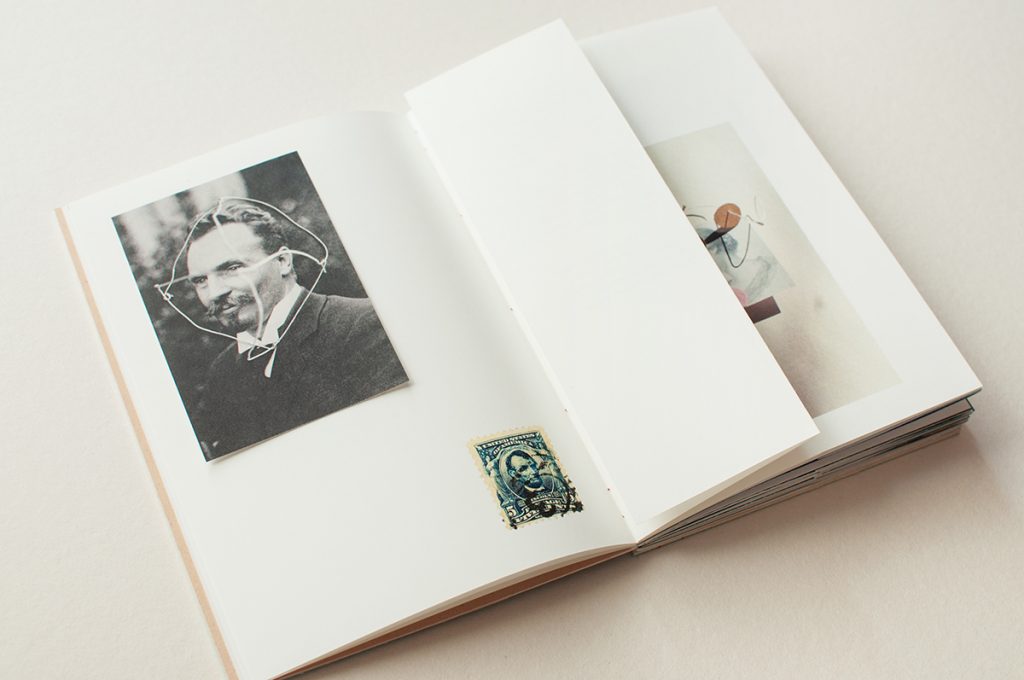

Borissova explains that she happened to stumbled upon a thin book about Leroux while visiting Tallinn, and became fascinated—she scoured the internet looking for information, and bought archival materials she found, including photographs, postcards, and flyers, on eBay and at flea markets. In Let Me Fall Again, she presents these archival materials, sometimes on their own and sometimes re-photographed as objects adorned with physical flourishes like curled strings and circles, together with some of her own original photographs. Throughout the book, she illustrates this sense of toying with history: the playfulness of the manipulation not only reminds us that she’s reconstructing his story through her imagination, but also conveys the lightness of it all. In other words, she doesn’t want to focus on the threat of falling, or portray his death as sad, but rather, she wants to argue urgently for the levity required to take a leap at all.

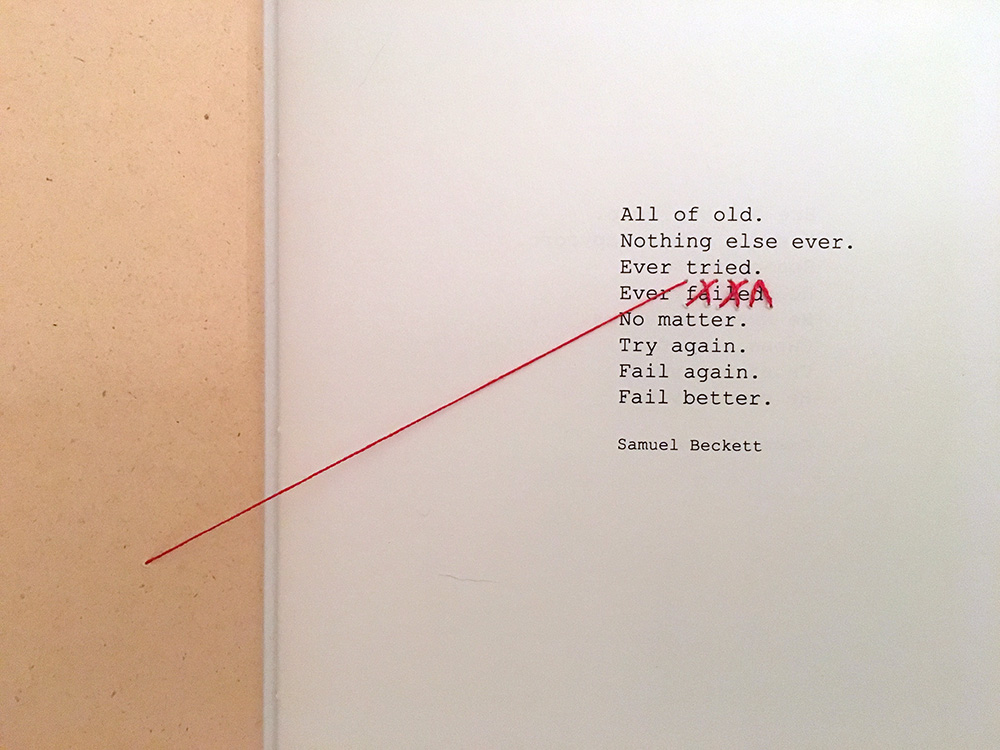

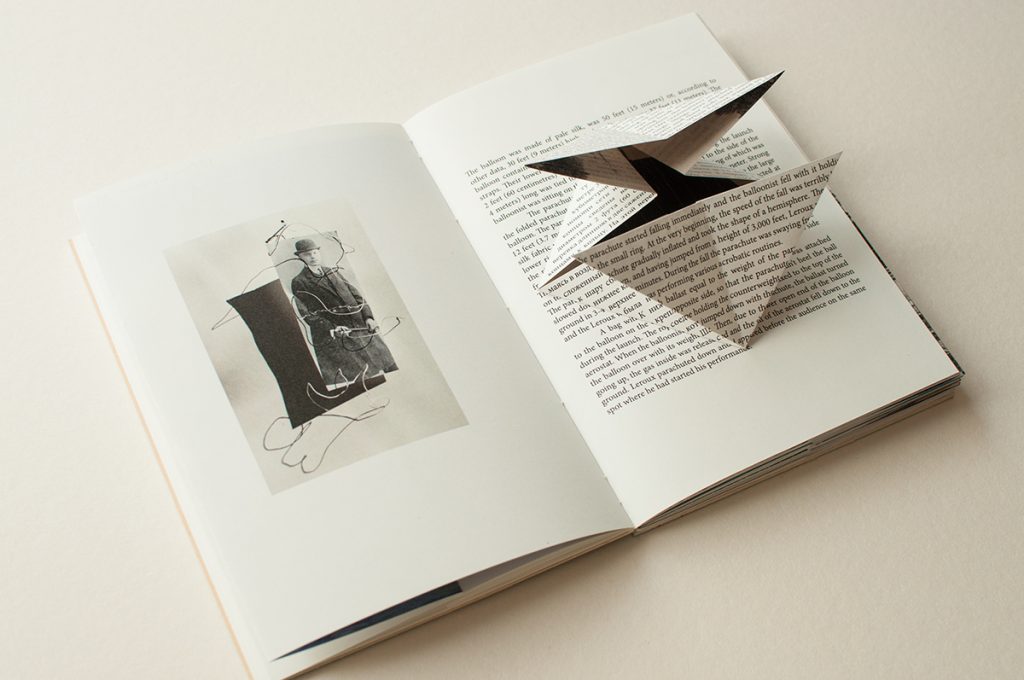

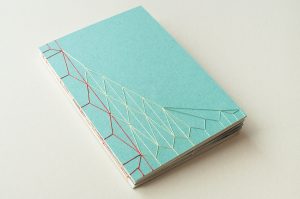

The book is magnificently constructed. Borissova has been making her own books for years, with each taking an entirely different format or method, and in this latest edition she demonstrates a deep love and precision both for bookmaking and her subject matter. She introduces intricate folds and accordion-style image fold-outs, hides texts (in English and Russian) behind page folds, with sentence fragments redacted by carefully placed red-threads, and, in what was for me the most moving element of the book, encloses a folded letter that she’s written to Leroux.

The letter, which begins “Dear Charles,” is of course not to be taken entirely literally since he is long dead, yet through her letter, we better understand her motivations and connection to her subject. Her letter serves nearly as a project statement, though is given an emotional charge by her efforts to communicate with her source of inspiration. She writes across time to meet him, just as he traveled through time in an Estonian book and in surviving ephemera to meet her.

“Two years ago,” she writes, “I began to wonder about the notion of the fall and failure in artistic practice.” It was around this time that she learned of Leroux, fueling her fascination, and began to see her own work as an artist as a sympathetic metaphor to his literal act of leaping.

“The gap between the initial intention and realization of artwork can be seen as an artistic failure. However, if unsuccessful attempts are not regarded as the final result, it encourages artists to work more and gives them opportunities to grow.” Therefore, to not leap at all, is to fail. Well, when we consider Leroux’s death at a young age, which can only be seen as a “final result,” it’s plain that this is a romantic view to take. It favors the unflappably bold.

Perhaps it would be wise to separate the metaphorical from the literal. Because we are mortals, it is literally a matter of our survival (both mental and physical) that we learn through experience which are the risks worth taking. Because we are beings of agency, we choose the shape of our lives, including death. Would Leroux be satisfied with the outcome of his final jump? Truly, no one can say but him. It is not a trivial thing to take responsibility for the entirety of your life.

As for Riding the Dragon, whose mission is to help creators survive the process of their creation, I’m careful to make a distinction between living life and making art according to your own terms, and engaging in poetic suicide. There is a cost that comes with leaping, which we won’t be able to measure nor fully understand until we have lived through it. We must live our lives, and this means pitting the safety of our selves against the ecstasy of our expansion and experiences. It is Eros versus Thanatos, bound in a unrelenting tension inside our frail, expirable bodies. Moment by moment, we choose, so we must choose well.

Yes, there are those who choose to leap. But those who do not likewise love the process of picking themselves up again will end up choosing their final fall.

Let Me Fall Again, because of all its delicate but exacting folds, feels both precious and playful. It is without question a product of Borrisova’s doting love; for bookmaking, for her muse Leroux, and in particular, for falling into the unknown.

Let Me Fall Again has been produced in an edition of 239 handmade copies, based on Leroux’s 239 jumps. It is signed and numbered, and available directly from the artist.

Let Me Fall Again has been produced in an edition of 239 handmade copies, based on Leroux’s 239 jumps. It is signed and numbered, and available directly from the artist.