"When you do something very important, you change deeply and it’s impossible to go back. Every cell in your body is changed. This is why you have to be prepared."—Pierre Liebaert, in our interview on rituals.

The Art of Computation: An Interview with Philipp Schmitt

Computed Curation is a new book of photography by Philipp Schmitt, a German artist based in New York. Well, perhaps it’s more accurate to say the photos are by Schmitt, but the book is by a computer.

Schmitt is something of a hybrid between an artist and computer scientist. He creates works that reflect on the social and cultural dimensions of data and computation. “I’m interested in how computation influences us,” he says, “and how we try to make sense of the world through computation.” In this interview, he speaks about the way computers see, the mistakes they make, and what it can teach us about ourselves.

Tell us about Computed Curation. How did you arrive at an algorithm-based book?

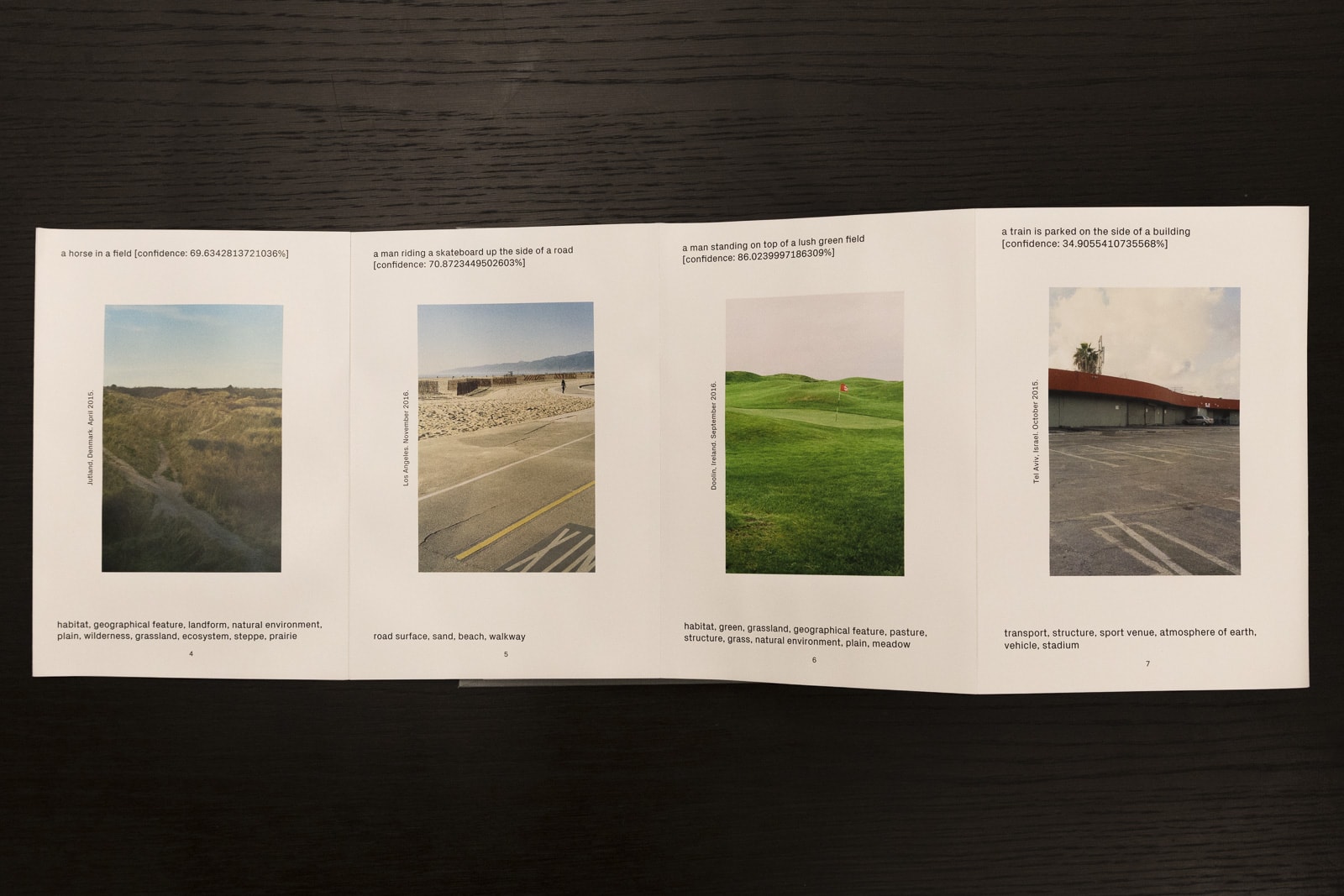

The photobook includes pictures that I’ve taken over the last five to seven years, and is curated by using various computer algorithms that caption each picture, categorize it using tags, analyze the composition, try to figure out the content, and then arrange them in a way that would be a continuous flow. Obviously a computer would not or could not curate in the same way a human would, so through this algorithmic lens things end up close to each other that I would never connect myself. The computer has no intelligence whatsoever—it’s just a sort of mathematical logic that created this—but as a human I can project so much onto what I see. There are some strange and fun connections, which you can interpret as poetic if you want to. But there are also flaws where you can see the shortcomings of the computer, for example a picture of a person that has their hand next to a trash can ends up being labelled as “a man throwing a frisbee.” At first this can seem a little silly, but if you look a bit more into the politics of the computer vision world, you can understand it happens this way, and that it’s not random nor AI.

What is it that the computer sees then? It can’t discern what a picture “means” for example, right?

No, it can’t. Right now in the media there’s a lot of talk about artificial intelligence and machine learning—terms that get very misused—and if you sprinkle a little science fiction on top for inspiration, you get these ideas that computers can think or that they can see. Computers definitely do not see like humans, and definitely not with any consciousness; it’s just a mathematical way of seeing.

Computers can learn from examples how to recognize something. If we give a computer a lot of pictures of apples, then it might learn some pattern, like in a picture of apple there is often a red pixel next to other red pixels in the center, and the corners of the picture are usually not so red. This is one way that you can form the concept of an apple, although it has nothing to do with an apple. An algorithm will never bite an apple, or taste one, or pick one from a tree.

How accurate is this model of computer vision?

Generally, computer vision has been conflated with machine learning or deep learning. This technique is very successful right now, and there’s a lot of research in this area. Computer vision is very advanced in constrained applications. On benchmark data sets that have a million pictures of different things, a computer now can perform superhuman performance, that is, it can recognize things more accurately than a person. But if you bring that method into the world, and let it look for example at my photobook, you get this weird stuff that doesn’t make sense at all. So, in constrained lab settings it works very well; in the real world it is often problematic. There are some examples of this in the book, where the captions don’t match the pictures, and this is all very innocent but it’s also being used in surveillance. Drones are controlled using similar techniques, so it’s also being deployed in a lot of ways that are also problematic. And remember also what I said earlier: a computer has no conception of what an apple tastes like or what it is, it just makes a statistical inference of the thing.

I can’t figure out if you’re an optimist or pessimist when it comes to this technology. How do you see it, as a game or a threat?

To me, it’s really exciting that I can put a picture into a computer and out comes a label that tells me that it contains an apple, even though nobody programmed the rules to do this and somehow the program figured it out by looking at a lot of apples. I think technology is extremely fascinating but, on the other hand, this technology is being used in some very problematic cases where not only does it not work well but we shouldn’t be using technology at all in the first place. It’s enabling even more computational surveillance, both for military use and by capitalist corporations. As a tinkerer and an artist I’m extremely excited. As a citizen, I’m concerned.

Where do you personally put the ethical boundary around this technology?

I don’t know. There will always be applications that are beneficial. Well, if you have a great government surveillance camera system, it’s beneficial for some, just not for many others who don’t have any real power. So, I think that no matter what gets made, nothing is exclusively for good when it comes to technology; it’s always much more complicated than that.

But also, speaking for myself, I’m far less concerned about a robotic takeover or the singularity than I am about even more extreme exploitative capitalism or surveillance. I don’t see the robot apocalypse as the problem.

How would you personally rate the algorithm as a curator? Were you happy with the result?

I think it did really well in terms of making things that I find surprising and so odd that they’re really engaging to me. I don’t know that I would feel the same way if this would be for example my family photo album, because then things would be all over the place. In a family story, you look for another kind of narrative. As an art piece it works great, as a personal record it doesn’t.

This is half-joking, but are you worried that your algorithm would ever put curators out of work?

No, I don’t think so. (laughs) My phone sometimes sends me a notification that it made a video for me, for example highlighting my best moments from Boston in 2017. This is computationally curated. I like these videos because they bring up memories, but I don’t think any serious curator is interested in this. I don’t know much about curating in a museum, but they probably have guiding questions or historical questions, and I don’t think there’s a risk of replacing the part of curation that is an artform itself.

Let’s talk about your work Genesis, which is also using machine learning to arrive at an act of independent “creation.”

That was actually a really small project, with much less thought and time to develop than some of my other work. I was playing with these deep learning techniques that are based on something called “generative adversarial neural networks,” which is a machine learning technique to generate pictures similar to what a computer has learned. A computer gets to see a thousand, or let’s say a million pictures of faces, and then is able to generate new faces that are not just copies of the training data but somehow ideally more generalized concepts.

Just to be clear, adversarial networks are basically when multiple machines are pitted against each other to speed up their learning?

Yes, one learns to generate faces, or whatever you’re training with, and the other gets presented with the picture and has to guess whether it’s real or fake. The first machine gets better at creating more realistic faces, and the second machine gets better at determining fakes.

I was interested in how I can use my own data to do something like that and not rely on these standard data sets that other people are using. A lot of the research papers working on this rely on only a few data sets: one with cats, and one with celebrity faces. Really funny. But it’s problematic to work with your own data set because ideally you would have millions of photos available, which is not easy to come by especially if you want to respect copyrights. You could crowdsource and get images from other people; sometimes it’s done for free but a lot of times it’s done through these micro-work platforms, so people get paid small amounts to do this work, which is also gig-economy problematic. I think Google has its own work centers somewhere in Asia where they employ people to tag data sets, so there’s a huge amount of offshore labor involved. And of course you can also do it yourself if you’re an artist or someone who wants to make their own, but it’s really labor intensive.

So I ended up using a little book of beetles that I found at a small library in Brooklyn, called the Reanimation Library, which collects misfit books that no one really wants but are often beautiful. They focus a lot on visual material, and I found this book of beetles and then went on to make my own series of beetles. The title Genesis is related to the question of where the data comes from, and also to the idea of creating my own lifeform.

There’s an artist in the UK, Anna Ridler, who did a similar project where she made a data set of 10,000 tulips that were all bought on farmer’s markets and manually photographed and tagged, and that obviously took a huge amount of time. So there’s other people working with similar questions in mind.

You seem to be actively aware of the social impact of your work. Does it trouble you that some of your machine learning tools might be used to facilitate some ends that you disagree with?

In this case, no, because I basically used open source software. Aside from changing the training data, I didn’t produce anything problematic. I’m more concerned that I should be focused instead on issues that are more serious. Working with deep learning may be interesting, and it’s also interesting to have a critic contribute to a critical discourse, but on the other hand, if my computer wasn’t running for a week on this project it would have produced less emissions. That is maybe the larger concern.

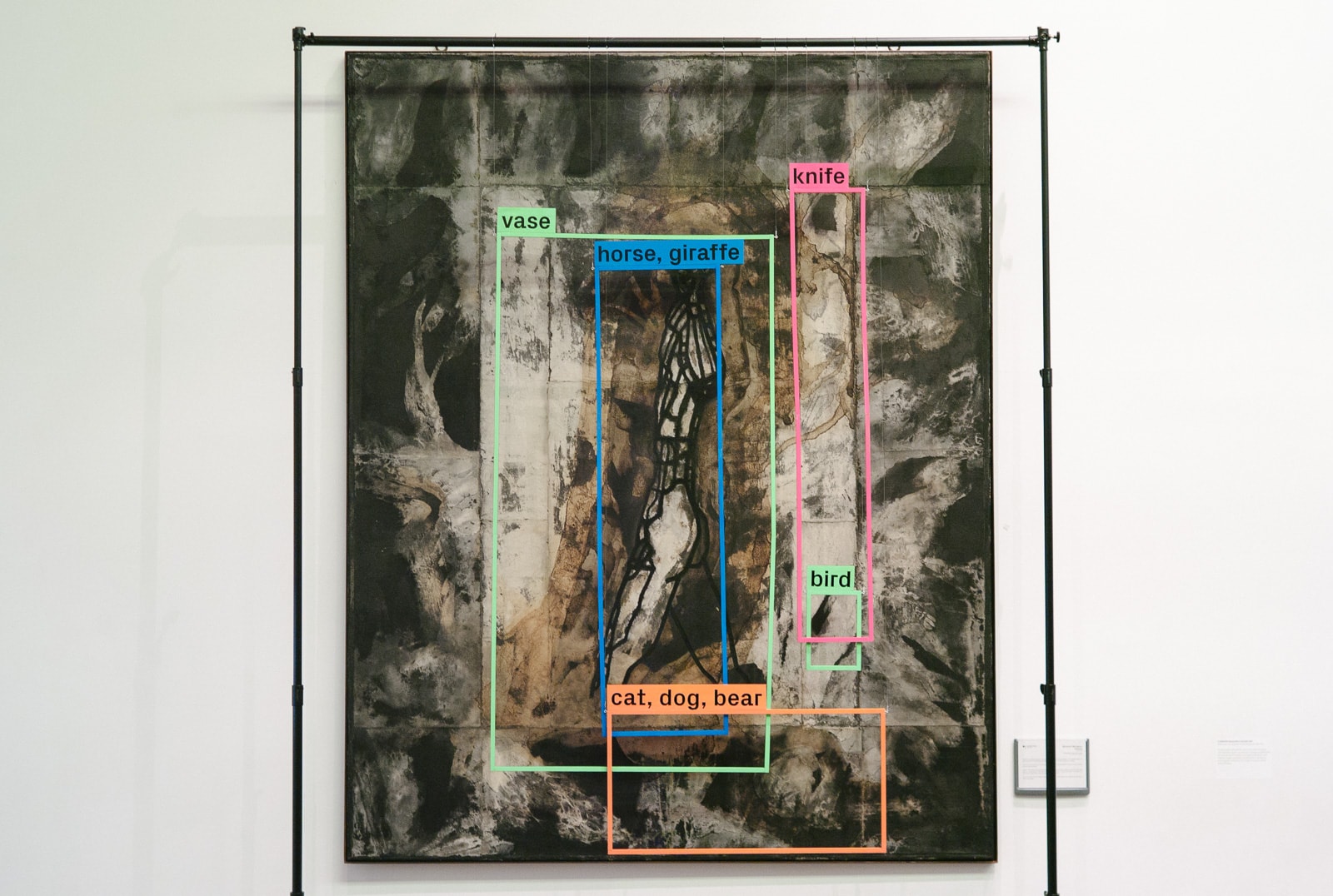

In your work A Computer Walks into a Gallery, we see how a machine interprets an artwork, and it’s funny because it gets everything wrong but is somehow still fascinating to see what it sees. It reminded me of the story of the man who mistook his wife for a hat because of visual agnosia. So maybe it’s quite human after all. Would the ideal machine be able to see more like a human or somehow better than a human?

Probably human-like would be really boring, right? If it sees the same as what I see, I don’t think that would be very compelling. The question is, what would be a superhuman way of seeing? I don’t know what that is.

I don’t have the vocabulary to talk about classical visual arts, but the painting is not just what you see, it’s what it makes you think of, and what it makes you feel. Maybe if a computer could feel that, it would be very interesting. What’s exciting to me about a computer is how it gets it wrong, and how far it is away from being the same as me, and what I can learn about myself sometimes by looking at these mistakes. It turns out vision is not as simple as connecting a similar neuronal structure, because apparently there must be other stuff involved or I would see my wife and not a hat.

What is inspiring you at the moment?

Right now I feel it’s a very dark time for technology, so a lot of things inspire me in the way that they concern me. Also, moving to the United States made me so much more aware of issues that I wasn’t really faced with, or didn’t recognize, living in Germany. I think a lot about all the things that could be better.

On the other hand, right now I’m still working with deep learning, and there’s this concept of latent space, which is this idea of actual space, like my room, but a high-dimensional space. So it has more than three axes, it can have hundreds. We cannot understand or visualize these dimensions, but they’re somehow real. And even though it’s not a model of the world that’s based on cognition or intelligence it is somehow a model of the world. This idea is really beautiful to me, that there are these computers that can get really good at something, and we don’t understand why, and the solution to some extent is in this high-dimensional weird little world that we cannot see. And that we cannot see it is again the problem because we then cannot understand how the computer reasons or behaves. This is a perfect example of something that I find really beautiful and inspiring but at the same time makes me really concerned.

Computed Curation is available from the publisher, Bromide Books. See more from Philipp Schmitt on his website.