"Computers can learn from examples how to recognize something. [...]This is one way that you can form the concept of an apple, although it has nothing to do with an apple. An algorithm will never bite an apple, or taste one, or pick one from a tree."—Philipp Schmitt, in our interview about his new book Computed Curation.

The Bliss of Conformity: An Interview with Yingguang Guo

At People’s Park in Shanghai, parents congregate at a marriage market, posting signs about their single sons and daughters in the hopes of marrying them off. Chinese photographer Yingguang GUO (b. 1983) stands holding a sign with her own accomplishments, while men and women come sniffing around to assess her suitability for their children. She’s 33 years old and has a good education. Unimpressed, a man informs her, “A woman’s virtue lies in her lack of talent.”

Her presence at the marriage market has the purpose of performance art, but it springs from her personal experience as an unmarried woman in her thirties—a so-called “woman on the shelf.” In The Bliss of Conformity, Guo comments on the custom of arranged marriages through a contemplative combination of portraits of dissatisfied mothers at the bustling marriage market, grand shots of paper, and photo-etchings of the park’s flora. The black and white series feels weighty and drained of joy, and all too aware of the life-cost behind social expectations. In this interview, she tells us more about her photography project.

Tell us about your project The Bliss of Conformity.

It is about the notion of marriage in China: forced marriage, arranged marriage, and what we call “women on the shelf.” The starting point is my own feeling about being a Chinese woman; people are always concerned about me, and ask: “When you will get married?” and “Why don’t you want to get married?” and things like this. Well, I think, why should you get married by a certain age? This is your life.

I went to London to start my Master’s, and when I showed the pictures of the marriage market to my tutor and fellow students, they asked why parents would force their kids to get married. They don’t have this problem, and seem very relaxed about marriage.

How does the marriage market work?

It’s a matchmaking market of parents. At People’s Park, a lot of people come and the signs are everywhere – people hold them, put them on tables, or attach them to tree branches or on umbrellas because in Shanghai it rains a lot. It happens every weekend, it’s a regular thing. The market is really famous actually.

It’s a matchmaking market of parents. At People’s Park, a lot of people come and the signs are everywhere – people hold them, put them on tables, or attach them to tree branches or on umbrellas because in Shanghai it rains a lot. It happens every weekend, it’s a regular thing. The market is really famous actually.

Parents make ads for their children, and most of the time the children don’t have any idea their parents are doing this. People are walking around looking at the ads to find an interesting match, like with a house, good salary… there’s a set of standard things that you have to write down. If you meet those requirements, that’s the entry level.

Are the ads for both men and women?

It’s men and women, but for women it’s more difficult because there are many more “leftover” women than men. For men, it’s essential for you to have property and a well-paid job, but it’s not necessarily the same for women.

What’s essential for women?

Young age. When I did the performance in People’s Park, where I held my own ad with a hidden camera to see what happens, I didn’t write my age down, I only included the things that I’m really proud of, like that I’m a graduate. But the people there don’t really care about this. The first question they ask: How old are you? And when they learned I was 33, they just left.

Doing that performance was very difficult. When I went the first time, I just wanted to stop and go home. It’s very emotional. But I went for four days, one hour per day, and I persuaded myself that it’s only an art performance, so I’m there with different values. I’m against the traditional values, so they judge me at the same time I judge them.

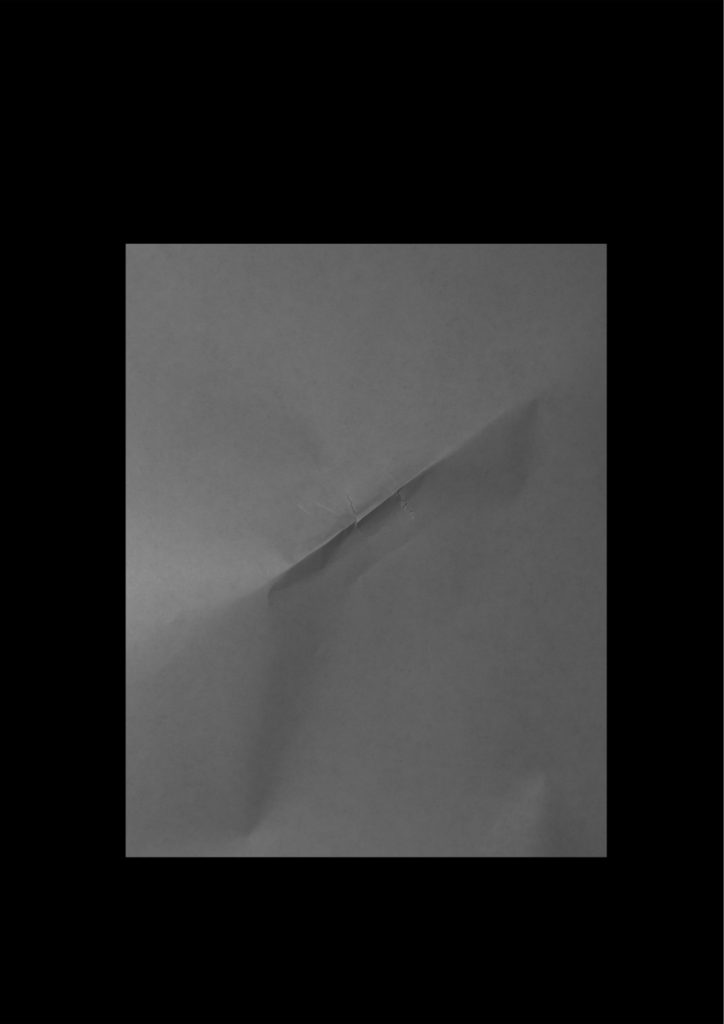

Tell us about the photos of paper that you include. They’re quite dramatic.

I remember the first time I went to the marriage market, I saw a mother who was trying to clip her advertisement to a table, and it was very difficult so she had to give it several tries. I got the feeling it’s very painful. I feel like the paper is not only paper, it’s people. Each paper represents a person. And I use the papers as a metaphor to imagine what is the life of those couples, those marriages that come from the marriages arranged at the market. Do they feel pain in their daily life in the marriage? Does it hurt as they try to maintain these relationships?

I remember the first time I went to the marriage market, I saw a mother who was trying to clip her advertisement to a table, and it was very difficult so she had to give it several tries. I got the feeling it’s very painful. I feel like the paper is not only paper, it’s people. Each paper represents a person. And I use the papers as a metaphor to imagine what is the life of those couples, those marriages that come from the marriages arranged at the market. Do they feel pain in their daily life in the marriage? Does it hurt as they try to maintain these relationships?

And what do you think, does it hurt?

I interviewed some of the people around me whose marriage was arranged by their parents. They share pictures on social media, and they look really happy. There’s one woman I know in a group chat who is like this, posting happy pictures on social media, but underneath that, she says can’t bear it, and she’s very sad and disappointed about her marriage. She feels surprised, but people just respond with: “Yeah, well, that’s how marriage is.”

It’s not just the people in the arranged marriages that you’re commenting on. The mothers in particular look so miserable.

I really don’t know why they are unhappy: is it their life or their children’s life? For example, my mom, she got married at a very young age and I don’t think she has her own life. Her life is around me and my father. This is what it’s like for most Chinese women.

I really don’t know why they are unhappy: is it their life or their children’s life? For example, my mom, she got married at a very young age and I don’t think she has her own life. Her life is around me and my father. This is what it’s like for most Chinese women.

So, I think, I’ll be a “new Chinese woman.” I’m well educated, I’ve seen different ways of life for women in this world, and I can choose my life, but … older women still try to force our generation to conform to the way they agree a woman should live. A woman should be married before a certain age, even if she has already found her way of living, and is absolutely happy with it.

Before I did this project, I’ve been thinking a lot about the context. China is going through this massive economic growth but it happens so quickly that there’s a lot of really bizarre things happening. For example, now on TV, there are programs where you can watch this kind of matchmaking or arranged marriages. Those kind of values are still prevalent. There are also the influences from the population, for example, there was the “one child policy,” which in recent years became two children. We have an aging society—there’s more older people than young people—and the young labor is not enough to sustain the growth of the economy, so the government changed its policies. Regardless of one child or two, it’s still a manipulation of how many children you can have. That influences the media and how the media communicates, which then influences how the general public think about marriage, giving birth, and all kinds of domestic issues.

Before I did this project, I’ve been thinking a lot about the context. China is going through this massive economic growth but it happens so quickly that there’s a lot of really bizarre things happening. For example, now on TV, there are programs where you can watch this kind of matchmaking or arranged marriages. Those kind of values are still prevalent. There are also the influences from the population, for example, there was the “one child policy,” which in recent years became two children. We have an aging society—there’s more older people than young people—and the young labor is not enough to sustain the growth of the economy, so the government changed its policies. Regardless of one child or two, it’s still a manipulation of how many children you can have. That influences the media and how the media communicates, which then influences how the general public think about marriage, giving birth, and all kinds of domestic issues.

Tell us about your combination of media—the photo etchings, the documentary photos, the paper.

My project is like visual research into women on the shelf, arranged marriage, and the irrelationship—the forced intimacy—of it all. I want viewers to experience those forced relationships, and the feeling that comes when you see the harsh treatment of delicate papers.

Yingguang Guo was nominated for the Discovery Award of the Jimei x Arles International Photo Festival 2017 and thereafter was named the winner of the Madame Figaro Women Photographers Award. The Bliss of Conformity will be included in the official Rencontres d’Arles programming of 2018, and will be launched as a book from La Maison de Z, at the Cosmos Book Fair. (See more about the book.)