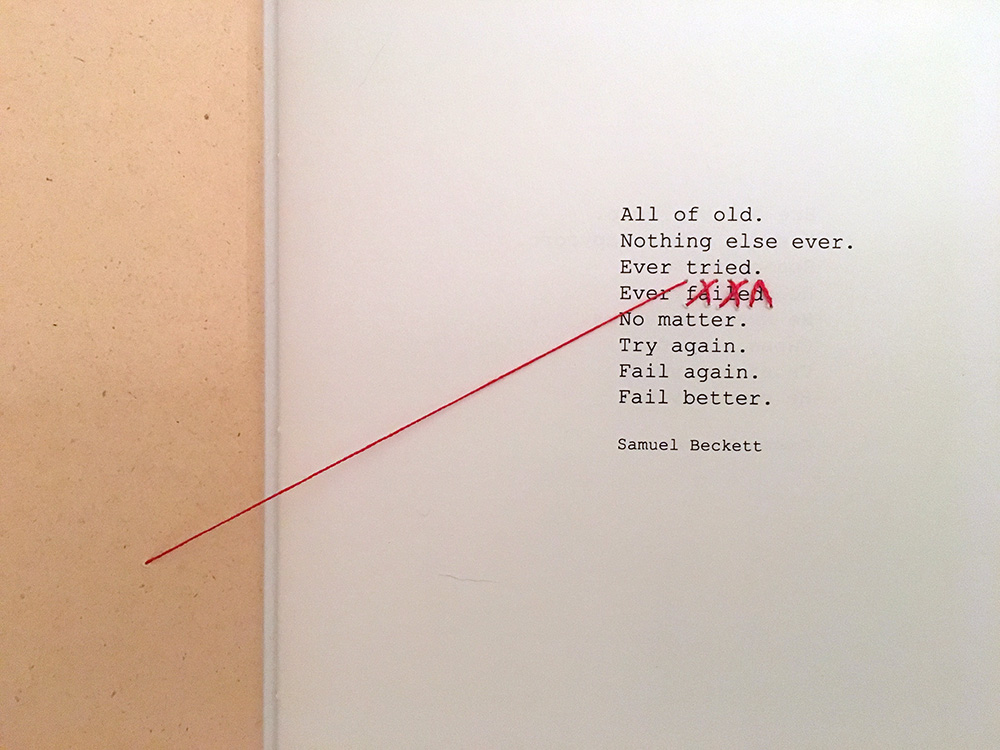

Olga Bubich’s self-published book, The Art of (Not) Forgetting, brings together emotionally potent memories of around thirty Belarussians, collected through interviews. Through personal stories, the author interrogates individual and collective memory.

A Nude by Any Other Name

The female nude: a genre of photography that is heavily tried and ambiguously true. Much critical thought, not to mention activism, has been put to the explication of the pervasiveness of the female nude in art over the last several decades, with little effect beyond scenting the nude with an intellectual perfume that lets us enjoy it in public more freely. If we say it is art, it spreads on distinguished white walls and catches a rich price. If we say it is filth, it spreads on screens with the virulent speed of naughty desire. One way or another, it spreads, in evidence of an apparently irresistible desire to place naked women on display.

Men, on one hand, reckon with this state of things from the perspective of authors or viewers. They may try to explain (or justify) the presence of these nudes, whether we’re speaking of John Berger’s analytical work Ways of Seeing, in which he writes, “Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at,” or more recent, progressive articles like Conor Risch’s “No More Bad Nudes,” (PDN, December 2018) in which he argues specifically against the creepy mode of exploitation in which men use the excuse of art to get women naked.

Women, meanwhile, work through their own position on the evolving use of their bodies for aesthetic purposes. Within photography, this public process takes place on both sides of the camera: women continue to be models and also gain wide new ground as authors. Sometimes, as in selfies or self-portraits, they are both model and author.

While I suspect that women’s reasons, diverse though they may be, for posing nude have remained relatively stable over time, the evolution of women authoring nude photographs poses a more intriguing mystery. Some women actively participate in the boys’ club of objectification, or play to the imagination with a girl-on-girl fantasy as we imagine a naked woman sensuously posing for—seducing!—her female photographer. Perhaps others take part in the “tradition” of the nude because they’ve seen that kind of work exhibited and sold widely in galleries, and swallowed whole the myth that qualifies it as “serious” art. Others, as I’ve argued before, may be trying to reclaim ownership over their own representation by rewriting how the female is portrayed. Still others use photography as a medium to work through their relationship to their own body, perhaps following childbirth, some injury, some emotional trauma, or the mere fact of living while female.

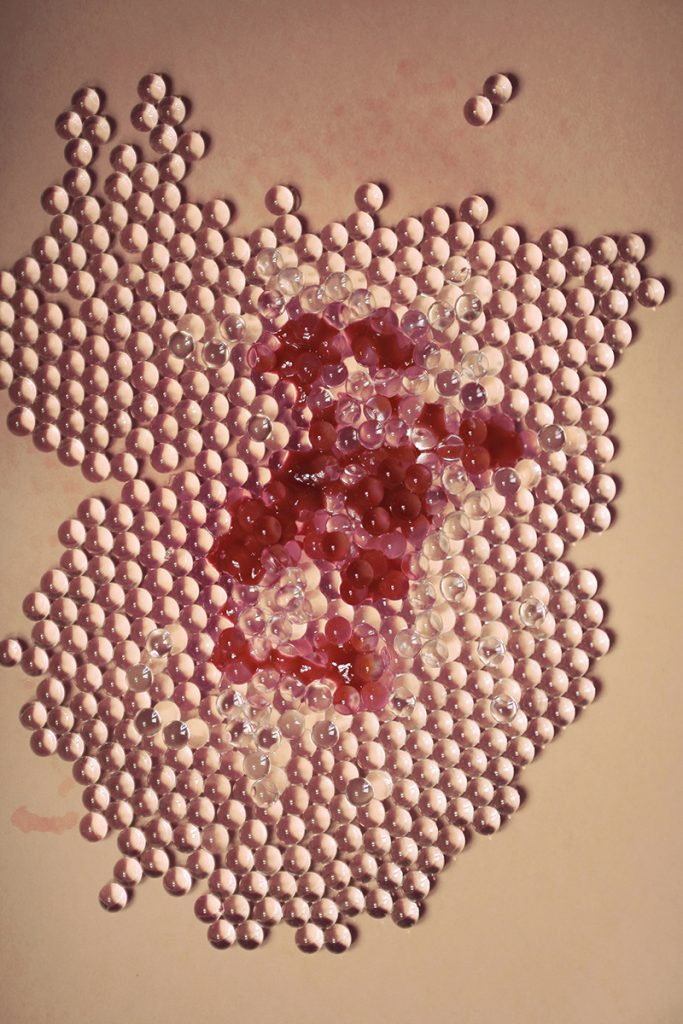

In “foam with coffeepowder,” a new series from German artist Nadine Blanke, we can see some combination of the last two, simultaneously deconstructing and reconstructing. Blanke is interested specifically in how we tend to see the body of mothers: What was once a sexual playground is transformed—through our looking—into a receptacle for growing and then nurturing a new human being. The maternal body is no longer an entity in itself, but a vessel for ushering in the next life.

Blanke combines photos of mothers with visual metaphors of, and references to, the feminine sex. It revels in the biology of being a living, breathing creature, capable of birthing other living, breathing creatures, yet takes a sober distance, or even alienation, from sex. The lush colors are ripe with sensuality, while the clinical eye and formal aesthetic detaches from sexuality, drawing our attention to the difference between the two. The title, too, “foam with coffeepowder,” is so stripped of sexuality that it’s more at home on a shopping list than a sext.

The women are portrayed as naked bodies, yet, Blanke clarifies, “The nude is to be seen naked by others—the spectators—and yet not to be recognized for oneself.” Therefore, she says, the women portrayed are not actually “nude.” It is a subtle distinction, and arguably one over which she cannot maintain control: While it could be true for Blanke and for her models that they are not “nude,” the viewer may ultimately retain the authority to see them, regardless, as nudes.

In the courtship between “looking” and “being looked at,” there is a negotiation. In person, this is a dialogue that passes back and forth between the parties, while in a photograph, the case of “being looked at” is already written while the arguments for “looking” can carry on, unhindered and perhaps full of misunderstanding and a false sense of entitlement or ownership. Artistic concepts and intellectual depth may give us something to speak about as we look, or offer us who care to engage with them a way of rethinking how we look, but it could be the case that this is just an elaborate rouse that enables us to participate in the base activity we mean to comment on—that is, ogling female bodies. For all the different motivations and methods of portraying the female nude, we may ultimately be confronted with the same end result: an image that frees us to look at and make judgments about the female form.

Is there a “right” way for women to reclaim their ownership and agency of their bodies? Women who do not participate in defining their image seem to suffer from the usurpation of this right, as men and others define their image for them. As women seek to define themselves and their image on their own terms, there arises an opposing force to manage the results. When selfies became a phenomenon, and females practiced defining their own image, there was (and is) a wide cultural backlash against the narcissistic “attention-whoring” of “girls.” The evident message: for a man to sexualize a woman is acceptable, but for a woman to sexualize herself there must be something wrong with her. A woman may make steps towards a de-sexualized image of herself, but truly, is there any part of the female experience that has not been turned into a fetish commodity for men to consume as erotica?

In Blanke’s series on mothers, there is the conscious effort to comment on the difference between the “body” and the “nude,” as well as “sexuality” and “sensuality.” It is a familiar space, as anyone who has been around mothers knows well. The woman—finding herself transformed into a “mother”—must question her identity independent of her child, as well as her body as a source of sensuous pleasure rather than its function of producing milk, protection and warmth to a dependent. This redefinition is a critical aspect of the feminine world and worthy of compassionate attention and exposure. And yet, given the way that photographs function, how can women even open this topic of conversation without the risk of unleashing a fappening?

Put another way, in a question as old as the Garden of Eden, can women ever be naked without being nude?

Even the matter of nudity-as-self-empowerment presents problems. In a recent article on the spectacle that results from nude photographs regardless of their emphasis on empowerment, Suchitra Vijayan asks: “When a project is constructed around nudity and equated with freedom, does a woman who chooses not to disrobe for any reason then live in permanent unfreedom?” The article, Misogyny and Racism as Spectacle and Performance, argues that, in a world where nudity is still routinely used as a form of punishment and shaming, the act of asking a woman to pose nude to prove her supposed power is rife with complications and mixed results. The photographer, educated and skilled in visual culture, often defines the “vision” and “story” for the picture, which even when discussed with the sitter essentially disempowers and depersonifies them.

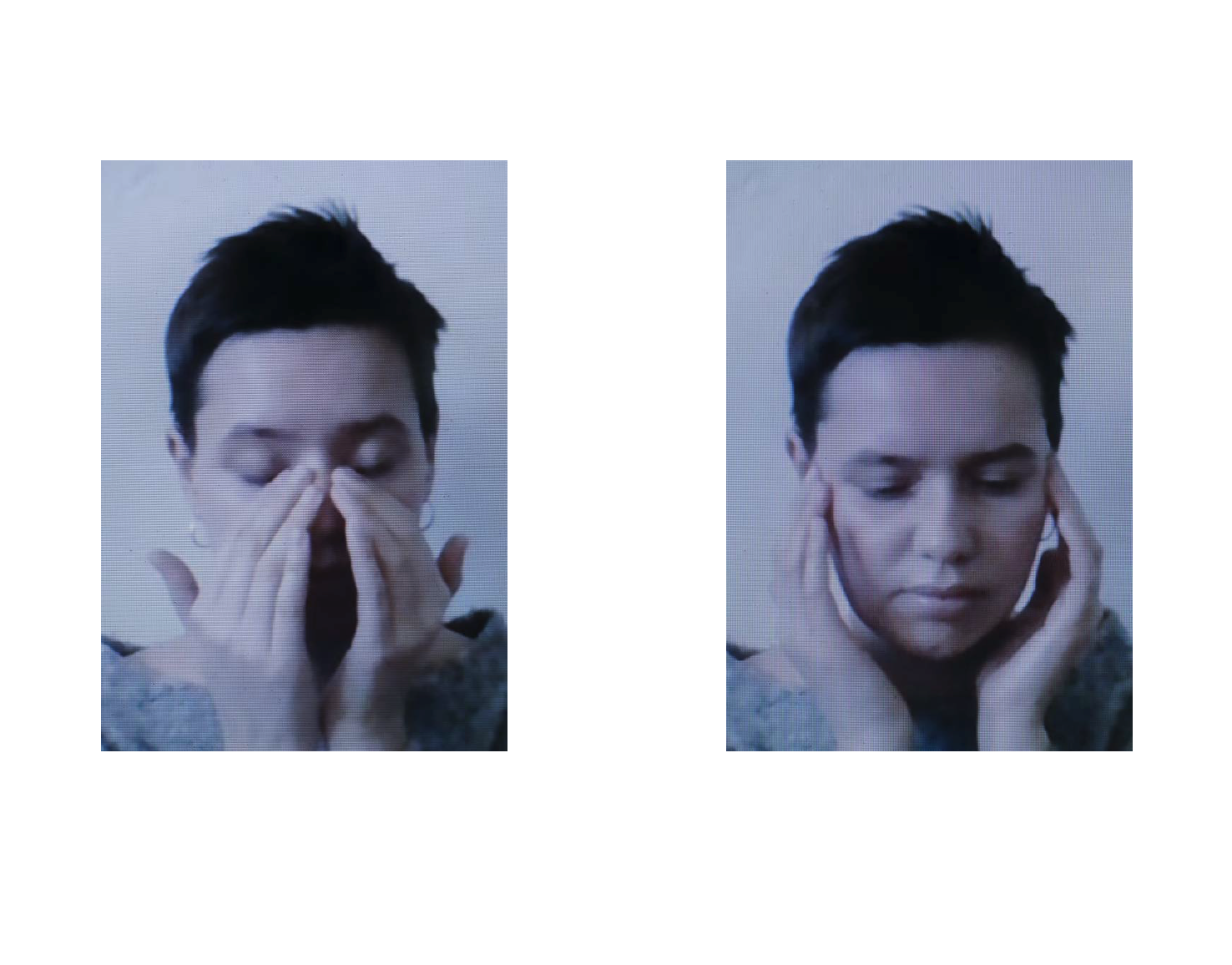

“I’m photographing the way that I feel when somebody is looking at me,” actress Audrey Tautou told me in an interview about her series of self-portraits, Superfacial. “Because I know that when somebody is looking at me, he’s coming with his own ideas of who I am, and maybe what kind of life I have, you know? And this little intellectual movement of the viewer, that’s what I wanted to catch.” Tautou is photographing herself, with full control over the way that she presents herself and also over which photographs she reveals to the outside world. She effectively takes control over her photographic image through the project, and yet, despite this, there is nothing to prevent the viewer’s ongoing fantasies of deciding that they “know”—through looking—who Tautou is.

This is perhaps the burden with which photography will always be faced. The power that we feel when looking is both real and illusory. We can own a photograph, pick it up and carry it around, or save it on our hard drives to be viewed at our length and leisure. The photograph is susceptible to receiving our explanations and expectations. And yet, what is photographed is only an image, packaged in a contained form and elusive from our shared experience of fluid reality. Even when held, a photograph, like everything tangible, defies any real or lasting possession. Photography, suspended at the crossroads of wanting and having, generates the ultimate seduction.

For all the steps that women have taken towards self-authorship, it seems likely that, at least when it comes to photography, the naked female will forever be vulnerable to being stripped nude.