Stephen Shore's new book Modern Instances: The Craft of Photography is an impressionistic memoir of anecdotes, reflections and influences by the iconic photographer and photographic educator.

Who Owns Your Memories? A review of Olga Bubich's photobook The Art of (Not) Forgetting

What is your most painful memory?

What is your most resourceful one?

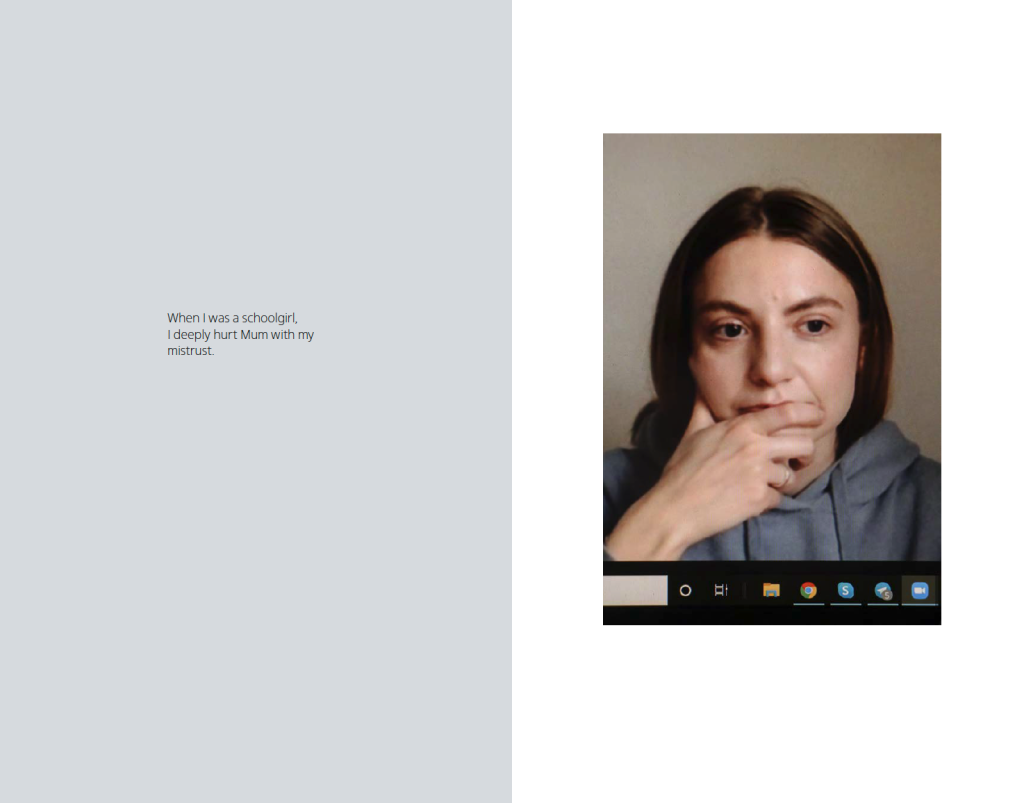

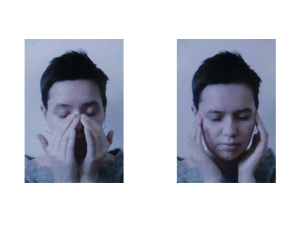

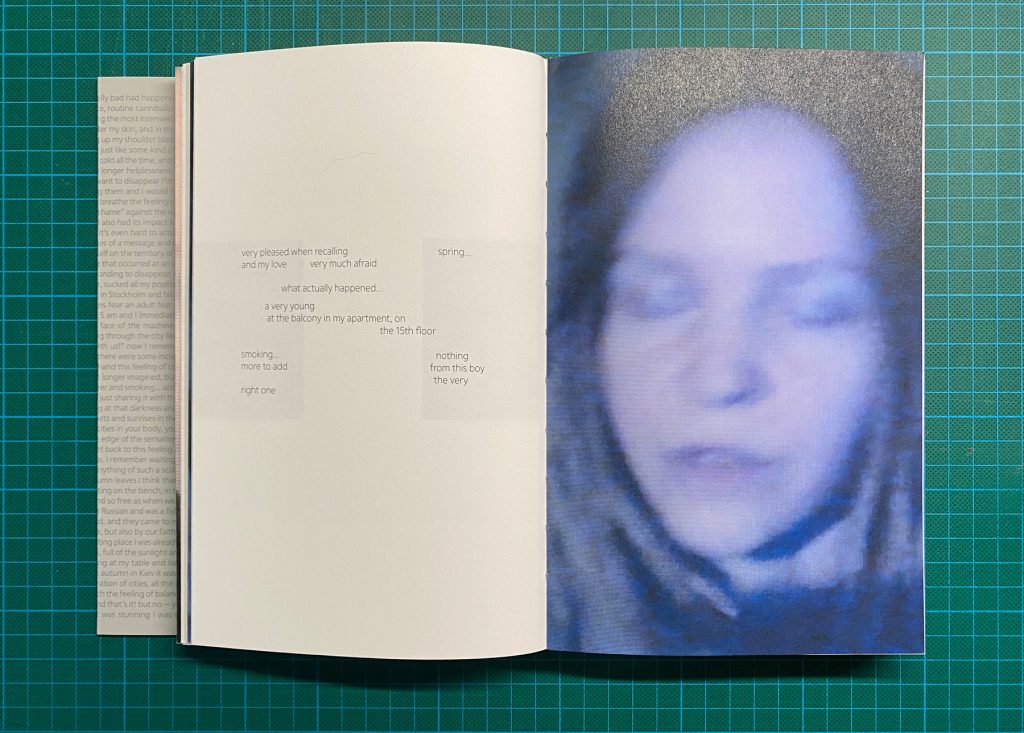

In Olga Bubich’s self-published book, The Art of (Not) Forgetting, the author brings together emotionally potent memories of around thirty Belarussians, collected through interviews. The memories are recounted in the first person, alternately haunting and edifying, as they portray intimate moments of powerful shame, anger, optimism, playfulness, fear, joy. Accompanying the texts are images of the participants, photographed intermittently during the interview, to convey the range of emotions as they recall memories holding strong meaning from their lives.

The stories are often of interpersonal relationships – family deaths or arguments, looking in awe at one’s baby, sharing a sparkling glass of wine on the Mediterranean – but Bubich’s motivation for the project is rather more wide-reaching. She writes in an article on Coven Berlin that through the project, which she began in February 2021, “around 4 months after the start of the protests in Belarus, I tried to use storytelling and photography as a means of opposing the regime of the last European dictator: Alexander Lukashenko.” Rallies erupted at the time, which were met by crackdowns. “People wearing clothes, scarves, bracelets, and even socks with the ‘wrong’ colors [referring to an opposition flag] were detained, fined, and given prison sentences.” Bubich emphasizes that these actions had the goal of not only silencing dissent, but preventing future generations from knowing and remembering. Essentially, the intention was to control the collective memory.

It’s worth clarifying that these political aspirations do not play a pronounced role in the book, but rather, are the author’s underlying thoughts behind the significance and meaning of memory. While some participants recall moments of being detained, for example, others speak of the ecstasy of singing “My Heart Will Go On” loudly on a yacht, or the awe of looking at the autumn leaves against the blue sky as a baby. They are simple emotions, deeply felt.

Bubich writes with conviction that memory is what makes us who we are, and quotes the Japanese writer Yoko Ogawa: “Being stripped of your memories is an act of violence that is perhaps akin to having one’s life taken.” Yet, memory is a tricky thing, malleable by ourselves and others, as well as the ravages of time. Our memories fail, and change. Often, we cannot choose what we remember, the body does it for us. The interviewees of Bubich’s project recall memories that are dear to them, but they also speak of memories that they wish they could forget – trauma and regret. Their stories invite us to consider similar moments from our own lives, and the value and impact of unwanted memories.

Bubich’s photographs are simple portraits of faces, yet pixelated, lo-fi, and poorly lit. It’s a form which became all too familiar for many of us during the lockdowns of Covid-19: video calls over Zoom or Skype. Perhaps during another period in history this would be a strange choice for an artistic project, but it’s certainly a matter of zeitgeist to say that, despite the poor resolution, it’s easy to read Bubich’s screenshots of video calls. The poor quality imagery even suits the project’s concept: the lack of clarity seems dreamlike, as though reaching into one’s subconscious to recall details and coming up short. What remains is the feeling.

Looking through the pictures, another aspect of the project comes into focus: There aren’t any men. “I photographed both women and LGBT+ people. When trying [to] invite men to share their memories, I did not receive any positive answer,” Bubich writes to me in an email. “I suppose it is connected with men’s inner feeling of fragility and fear/discomfort of being vocal about their painful experiences and memories in our culture.” This self-selection of participants feels like a limiting factor in the ability to reach broad statements about the human experience of memory, and yet, silence is another form of statement. The exclusion of male participants leaves a vacuum into which we can place our own projected thoughts about their memories and feelings. When we consider Bubich’s mission to counteract memory censorship, their willful decision to opt-out illustrates another aspect of memory: its privacy. After all, what is not spoken of cannot be redacted.

While Bubich is personally motivated by the context of Belarus, the book succeeds in capturing memories which feel rather universal to humans, and therefore making a statement on memory itself. Because of this, it’s easy to apply its meaning to other cultural situations, like the explosion of conspiracy theory followers and a reality corrupted by disinformation. The censorship of memory in the context of government oppression sounds dystopian and autocratic, while, simultaneously, it feels appropriate when the goal is to squash the spread of false narratives, such as former President Trump’s assertion that he won the U.S. election of 2020, which poisoned a population with anti-democratic sentiments and an inclination to violence. Both Belarus and the U.S. were rocked by the idea of a rigged election, and this was mostly achieved by trying to control the narrative: Creating doubt in people’s minds about what they know is often itself the goal.

Who has the right to decide a unifying narrative? Do we have the right to our memories, even when false? Do we have the right to broadcast all our unverified vilifying thoughts in media? The question, “who owns your memories?” seems naïve and obvious, until you consider the extent to which we all forget.

The Art of (Not) Forgetting has been self-published in a limited edition of 80 copies. See more from the project on Olga Bubich’s website, or on the Instagram feed dedicated to her memory research. You can also read her article “Overcoming Public Amnesia – Counter-Memory as a Tool to challenge Official Narratives” online at Versopolis.

The Art of (Not) Forgetting has been self-published in a limited edition of 80 copies. See more from the project on Olga Bubich’s website, or on the Instagram feed dedicated to her memory research. You can also read her article “Overcoming Public Amnesia – Counter-Memory as a Tool to challenge Official Narratives” online at Versopolis.