"Computers can learn from examples how to recognize something. [...]This is one way that you can form the concept of an apple, although it has nothing to do with an apple. An algorithm will never bite an apple, or taste one, or pick one from a tree."—Philipp Schmitt, in our interview about his new book Computed Curation.

Creative Potential A Review of Becoming Creative: Insights from Musicians in a Diverse World by Juniper Hill

In discussing creativity, a debate has long raged on: Are some people simply born with it and others are not? Are some destined to be creative geniuses, and the rest of us had better quietly accept our fate and get “sensible” jobs as engineers and bankers, or, if we’re really lucky, as underpaid support staff in the proximity of the genius? In her new book Becoming Creative: Insights from Musicians in a Diverse World, Juniper Hill arrives at the conclusion that, in reality, it likely depends on the culture in which you’re raised.

In discussing creativity, a debate has long raged on: Are some people simply born with it and others are not? Are some destined to be creative geniuses, and the rest of us had better quietly accept our fate and get “sensible” jobs as engineers and bankers, or, if we’re really lucky, as underpaid support staff in the proximity of the genius? In her new book Becoming Creative: Insights from Musicians in a Diverse World, Juniper Hill arrives at the conclusion that, in reality, it likely depends on the culture in which you’re raised.

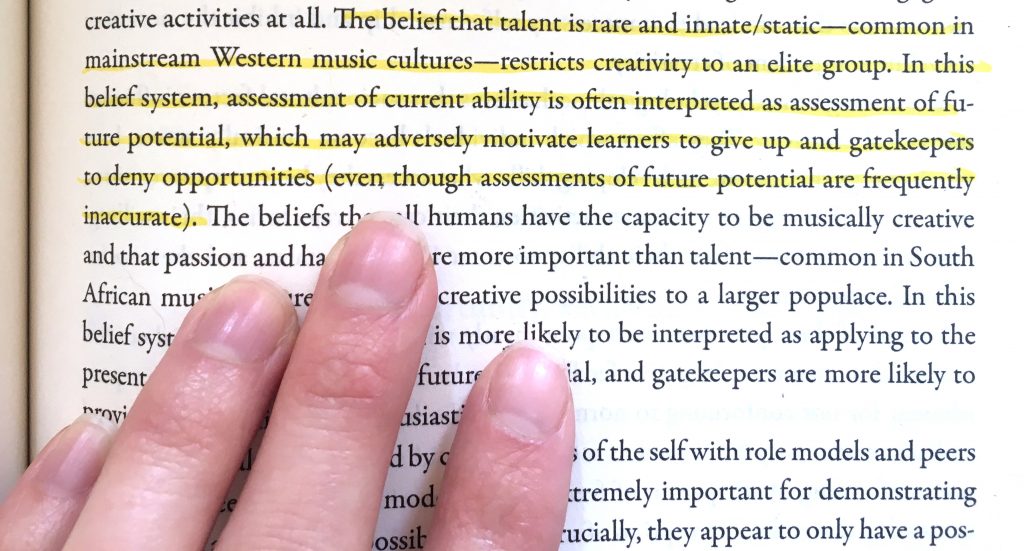

In a cross-cultural study of working musicians in Los Angeles, Helsinki, and Cape Town, Hill makes an interpretative phenomenological analysis of the personal histories, experiences, and viewpoints of contemporary musical creatives. “What varied noticeably by culture were attitudes about (1) the requisite balance between innate talent and passion/hard work and (2) how widespread latent talent or potential for musical creativity is among both musicians and the general population,” she writes. For those born in Western cultures, you’re far more likely to believe that creativity is reserved for an elite few who happened to be gifted. For those born in more communal societies, for example in South Africa, you’re more likely to believe that creative acts like singing and dancing are the domain of everyone. Xhosa musician Sabu Jiyana is quoted as saying, “Sometimes I’m shy, [and say] ‘no, I can’t sing.’ When you say that to my granny you get a hiding, trust me. [She would say] ‘you can sing. Or you can play an instrument, but even if you can’t play an instrument, you can sing. Just sing anything. Sing. Don’t give us excuses here.’”

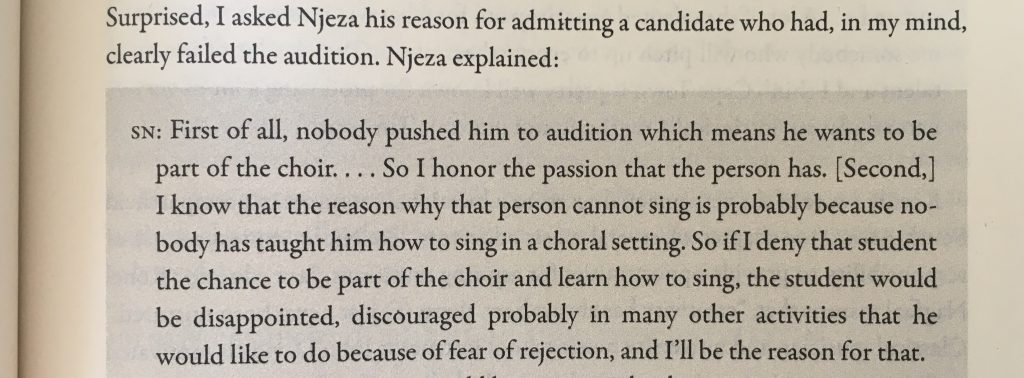

Why does this matter? Well, in short, because there is a difference between present talent and future potential. If, as an Angeleno, you try to sing and do it badly, you may quickly write it off; you were simply not born to be a singer. If, as a Capetonian, you try to sing and do it badly, your culture will likely encourage you to keep singing because talent is beside the point—music is inside everyone. And in that continuation, you may very well realize talent. “How quickly one learns is a common criterion for making initial assessments of talent,” writes Hill, “but it appears not to correlate with one’s potential to become creative at a high enough level to influence a tradition.”

Consider the impact of this fact against what Hill says about her field work in Helsinki: “I encountered a number of adults who had been told by an elementary schoolteacher that they could not and should not sing. They majority of them never became involved in active music making, and those who did struggled against significant psychological inhibitions.”

Beliefs about the innateness of creativity are often so embedded in a culture as to be institutionalized: In some musical education programs, students are evaluated simply on their existing talent or their ability to perform during an examination, while in others, dedication is valued over current skill level. Again, there is no correlation between those initial assessments of talent and ultimate potential, yet in some cultures, great psychological pressure is put upon the appearance of being gifted with creativity. This in turn fuels or withholds one of the significant factors of creativity: being granted the “permission” to be creative.

At first blush, this need for permission seems counterintuitive. Creativity is often touted as an act of nonconformity, rebellion, or assertion of independent personhood. This certainly can be true at its peak, when the formation of one’s self and one’s work achieve a certain hard-won harmony. Yet, turning the question on its head, we must then ask: who has the privilege to be nonconformative? Who is enabled and encouraged to be independent? Who has the luxury of being celebrated rather than punished for rebellion?

In the article My Life as a Failed Artist, Jerry Saltz traces his path as a hopeful artist who could not achieve the things he wanted creatively and so eventually became a critic, informed by his history as an artist. “When I teach today,” he writes, “I often judge young artists based on whether I think they have the character necessary to solve the inevitable problems in their work. I didn’t.” Creativity is a matter of action, yet also of psychology, and many have written (as I do) about the trauma and damage experienced while in the vulnerable state of creation. “Instead of gearing up and fighting back, I gave in and got out.” He then pivots: “But I learned so much about being a critic.”

Saltz’s anecdote moreover illustrates the phenomenon of how cultures are shaped, as we indoctrinate the hard lessons we have learned to those who follow us. His characterization of judging students based on their character is atypical of Western creative valuations, however his article overall is riddled with the prototypical self-judgment and self-loathing of not being sufficiently (which is to say exceptionally) creative.

Hill starts her book with a working definition of creative—a necessity of research which isn’t meant to be universal but practicable for identifying and describing patterns. “The six processes that musicians regularly experience while perceiving themselves to be engaged in a creative activity are (1) generativity, (2) agency, (3) interaction, (4) nonconformity, (5) recycling, and (6) flow.” What is striking about this structured breakdown of the apparent magic of creativity into a discrete list is that, to some extent, it could also be considered a checklist for human flourishing. It describes qualities of personal achievement and collective human advancement that are by no means guaranteed but blossom when conditions allow. Hill likewise gives no credence to the myth of the tortured artist, her research supporting the need of well-being in order to create.

Because Hill’s book is a phenomenological analysis of working musicians, it’s filled with excerpts from her interviews with them, offering diverse and beautifully observed insights from a spectrum of experiences. That is, while her process and conclusions are academic, they’re informed by the sensitive realities of artists. Becoming Creative covers a wide range of topics related to creativity—such as how creativity is formed, the various kinds of skills utilized in creation, the enablers and inhibitors of creativity, the economics of a creative life, among others—which are too numerous and in-depth to do justice to here. While she does focus specifically on musicians, her work resonates too with artistry broadly speaking. For those who work in the field of creation, it’s likely to find in Hill’s work a clear articulation of complex phenomena personally encountered. Ultimately, giving voice to that shared experience delivers balm to creation’s spiritual wounds and encouragement to continue.

Becoming Creative is published by Oxford University Press.