"I have to be creative on demand, because if I mess up an assignment then I'm probably not going to get a callback. That editor, or that publication, is not going to hire me again. And that is a very stark reality of photography, right? You have to be at your optimal all the time."—Dina Litovsky, on being creative on demand.

Brilliant Failures and Second Chances

Would failure by any other name taste just as sour? If we call it a “learning opportunity,” for example, does that make it more palatable? Well, to some extent, yes. What we call “failure” is often a matter of perspective, and can easily serve as an impetus for growth and improvement. If you harness your meaning-making capabilities to reframe an event in your mind not as a failure but as a productive part of the process, it loses some of its sting. However, if we pull failure apart, we realize it has multiple components: it is an event and it is an emotion.

Let’s first talk about the event of a failure, because it’s rather more concrete and understandable. There are many ways to define failure, and so to avoid getting bogged down in interpretations, let’s try to summarize it neatly as the lack of accomplishment for a determined goal.

Within start-up culture, failure has a tendency to be fetishized. There are countless inspirational quotes about how failing is necessary, to the point that if you haven’t failed yet, you’re just a rookie. Failure is a way of earning your stripes. “Fail fast, fail often” is an Agile concept that encourages small experiments, trial and error and moving on quickly from anything that doesn’t work, rather than getting quagmired in multiple-year projects that are fatally flawed without knowing it until much too late. There is absolutely some value in this line of thinking because, on the opposite end of the spectrum, failure is stigmatized. For those of the “failure is not an option” camp, to fail is unforgivable.

At the Lean Startup Summit Europe 2018, speaker Paul Louis Iske explained that failure remains one of the top four basic human fears, amidst terrorist attacks, death and spiders. Why? “First of all, because people want to achieve something and it doesn’t work. They want something and they won’t get it. The second reason to be afraid is because of thoughts like, What will people think about me? What will it mean for my job, for my investments? How will they look at me? And that’s a very human factor, why people are afraid of being a failure.”

It’s complex thinking, in that sense, that enables us to be afraid of failure. It involves theory of mind (imagining what others think) as well as the ability to imagine future scenarios (what will happen after failing). Yet, despite the fact that we all fail sometimes, and that failure is often a tool with which we learn, it’s a fear that persists. Considering all this, it indeed makes sense to try to alleviate this fear by creating a more open space for failure, by discussing the positive potential it creates.

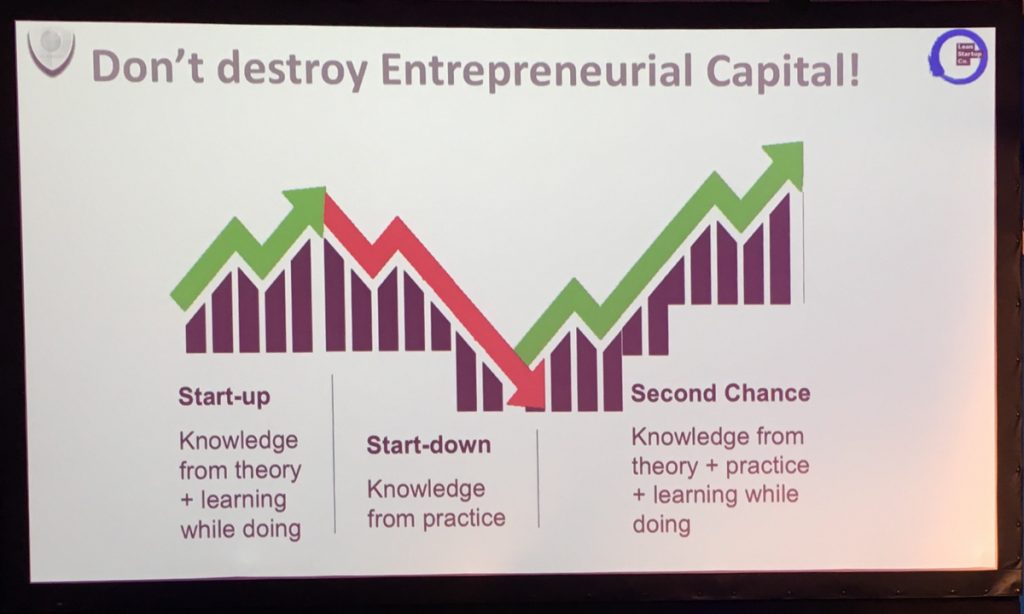

Iske, who has a background in innovation and is a professor at Maastricht University, has formed the Institute of Brilliant Failures as such a space. It came from his belief that people deserve second chances, which is to say, “It was based on research that showed that people whose businesses went bankrupt actually had a good chance of doing well with their next venture.” (from Harvard Business Review). Iske clarifies quickly that the first attempt must be a “brilliant failure,” rather than stupid or criminal. “If you try again, you have more knowledge, and it shows you have stamina.”

The Institute defines a brilliant failure as “a well-prepared opportunity with a different outcome than planned and a learning effect,” and Iske gives five criteria that an event must meet in order to fit this categorization:

- Had the best intentions

- Eliminated avoidable mistakes

- Experienced failure(s)

- Achieved learning or created value

- Inspires others

For example, he mentions the case of Viagra. It was developed by Pfizer with the good intention of treating angina, chest pains and high blood pressure. After six years of research, they came to the conclusion that the medicine did not have the intended effects—but the alternative effect on erectile performance made it valuable in an entirely unanticipated way. This is what he would call a “brilliant failure.”

Of course, most of us fail in far less spectacular ways, with the results of our effort being of no real marketable value. This is where it’s important to create value from the experience by learning from your mistakes. To do so creates the worthiness of a second chance. Iske poses the provocative question: “If you want to invest in someone, would you rather invest in their first chance, or their second chance?”

Following the start-up failure is the critical start-down period, which, if it’s harnessed correctly, can become a value-adding phase in the project and to yourself. “Because you learn, you get feedback from others, you start to have another perspective on what you’ve done, and this is very valuable,” Iske says, “You can say ‘I have a better idea now how to do this, or to do something else’.” Some development practices integrate this philosophy in the process – if you work with Scrum, for example, think of the retrospective that follows each sprint – yet this may not be something that occurs at the level of the individual, or the level of a company.

When was the last time you did a post-mortem on your failures, aside from rehashing and reliving the pain of it?

Let’s remind ourselves: by and large, failure is not seen as acceptable. The tolerance, or even embracing, of failure is often pretty much limited to certain entrepreneurial fields. Many areas, take healthcare for example, have no appetite for trial and error, despite the scientific method being a controlled method of exactly that. Creative industries have an overlapping mentality with entrepreneurship, so they may also embrace experimentation and the uncertainty that comes with it, but the result is still often unforgiving. Clients, customers and audiences can abandon an artist after a stunning failure. Or, even if they don’t, the failure may still sit with the creative, echoing in a private torture chamber of the mind.

This brings me to another facet of failure: the emotion. Much like the emotion that comes with the sudden realization that we are ‘wrong,’ there is likewise an emotion connected with failure. It’s a complex emotion, so we will each likely experience it with personal and subtle differences, much like what happens when we drink wine. Each of us will describe it slightly differently, with nuance of smells and taste. For me, the emotion of failure feels most like shame and embarrassment, together with notes of anger, fear, anxiety, and an awesome vortex at the center of my being that seems to simultaneously suck in all life and contain nothing at all.

The emotion is made all the more difficult if you conflate the act of failure with the state of being a failure. This concept has its kinship in Brené Brown’s description of the difference between guilt and shame, as mentioned in her TED talk Listening to Shame: “Shame is a focus on self, guilt is a focus on behavior. Shame is, ‘I am bad,’ guilt is, ‘I did something bad.’” It’s therefore important to make the distinction that failure—the event—is about things which happen as opposed to a materialization of self, so that when you experience failure—the emotion—you do not understand it as a personal quality, like being “smart” or “funny.” The emotion is yours, but it is not you.

Brown explains that she thinks the taboo of talking openly about failure is related directly to shame. She says of TED: “This is like the failure conference. No one that gets on this stage […] has not failed. I’ve failed miserably, many times. I don’t think the world understands that because of shame.”

Failing feels awful. And this is a good thing. I don’t mean it’s good to fail or to feel awful, but it is good that we have this emotional feedback. We have two innate drives that aid us in survival – to go towards things that feel good, and to go away from things that feel bad. (Let’s leave aside the neuroses that lead people to seek pain. This is in itself a symptom of dysfunction.) If failure feels bad, we will work hard to not repeat it, in the same way that once a food has poisoned us, we will take great pains to learn how to identify and how to avoid it. However, if we are numb to the failure—if we train ourselves to not feel anything—or even beyond that, if we convince ourselves that failure is a true good and we should seek it, then we will likely not teach ourselves to make wise decisions when it comes to risk. In the absence of a fear of pain, we will poke a sleeping bear and be killed before we realize any danger.

Emotions are tied to our nervous system – they are there to inform us about critical information about our environment as it pertains to our safety. As such, it’s not useful to discard our negative emotions without first understanding the message that they’re sending. It bears reiterating, too, that it is not useful to hold onto negative emotions after we’ve absorbed their message.

To become better equipped for a world of risk and uncertainty is not to neutralize or learn to enjoy failure, but to learn how to cope with it afterward. When I asked Iske if he had any practical suggestions for how to create this transformation internally, between “failure” and “learning opportunity,” he said the answer is about both your internal reaction and your environment: “We should accept about each other that we try hard. Most of us get out of bed in the morning not to waste time but to do something useful.” By acknowledging this about yourself, as well as others, we take the first step. The second step is to acknowledge that when you try something, it might fail.

“What I focus on is preparing for life after the pain,” Iske said. “What I try to bring is a new perspective: Okay, I failed. And I can cry about it or be angry about it, but let’s not stop there, let’s see what I can do next.”

Brown, in her talk, likewise advocates that it is not a solution to opt out of risk. She says: “Let me go on the record and say, vulnerability is the birthplace of innovation, creativity and change.” To overcome the shame of failure, however, she prescribes empathy as the antidote. To be vulnerable, and protected by the empathy offered by our human connections, we’re empowered to dare greatly.

Ultimately, the primary objective is not to eliminate the fear or pain of failure, but to reduce the stigma of failure so that we can speak about it and learn from it. It is worth repeating, too, that it is not worthy to actively seek failure. On the contrary, to be a brilliant failure, the number one criteria is that you must be acting with the best intentions.