"There is no artist mother paradigm. So, when I, as a middle-aged woman, make art, people assume it’s my nice hobby. They don’t take me seriously because it’s not a paradigm that we celebrate or that’s particularly visible, culturally. But being an artist mother is an identity that, once it’s articulated, people feel very strongly."—Hettie Judah, on the artist mother identity.

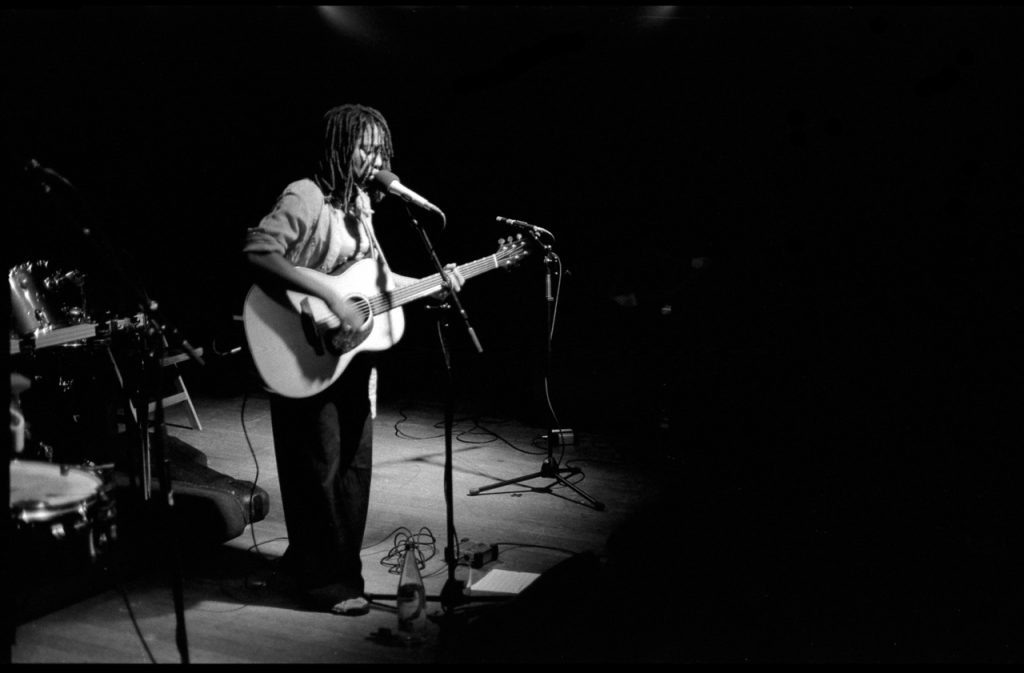

Art is a Deep Love of Humanity: An Interview with Musician Lake Montgomery

“Art is a deep love of humanity,” musician Lake Montgomery tells me wistfully as we hang up. She’s a singer/songwriter born in Paris, Texas, but has been living in various countries in Europe for the last eleven years. She’s now based in Edinburgh, but we first met when she lived in Amsterdam, and have since spoken many times about the practice of art. While she performs frequently and broadly, she maintains a career that is, to her fans’ bewilderment, essentially under-the-radar, preferring the intimacy of shared spaces to the remoteness of wide reach. In this extensive interview she speaks about the shame of busking, the confidence of asking for what you’re worth, being a useful part of society and committing to your craft.

You’ve been playing music for a long time, but you told me that you couldn’t or didn’t really perform in public until you came to live in Amsterdam. How did that you evolve? What was stopping you before, and what allowed you to get started in Amsterdam?

I did perform, but only casually, like at the end of a party when I was drunk enough and someone would say “Hey, she plays guitar!” then I’d play a song. Things like that started to get me thinking, “Hey, I could do that.” I’d travel a lot throughout the states, and it was a great way to make friends. I’d sit in on open mic nights and end up with a good handful or crowd of people liking me. It helped with my shyness, and that was the main thing stopping me.

In the States, it seemed to me at the time – or maybe it was just what I was exposed to – that you couldn’t want to be just a singer/songwriter. If you wanted to call yourself a musician, you have to aspire – your goal should be getting on MTV or on television somehow, making a million bucks, being a superstar. But being a fuckin’ superstar was never very interesting to me. It didn’t seem very earthy, you know… real.

Again, maybe it was my youth that I saw things that way. I don’t know if it was the culture, I’d still like to say it was America and not necessarily me.

Then, when I went to the Netherlands, a couple things happened. I was away from my home, and I think that had a big effect on me. I didn’t know the Netherlands was going to be my home for six years. I was welcomed there by a Dutch woman named Ans who loved music and musicians, so she was getting me into it, too, you know? I could see that there are people who can have just a normal life, being an artist. I was witnessing that. Ans encouraged me to play music on the streets, so I went ahead and did that.

What happened?

Not only is it interesting for me to connect to people anyway, but there’s something especially beautiful to connect to people who I have so little in common with. Like I’m speaking to aliens. And that was my way to say hello to the city, to connect with its people, and to feel suddenly, but deeply, a part of it. I became a part of the cogs of the community.

And they’ve got it going on in Amsterdam. I got into the open mic nights there and would immediately get booked for something else. They have little festivals, and these cultural events are subsidized, and they have culture centers that are happy to help.

It was just such a different experience than I had in the States, though I have to admit that I didn’t try there. It starts with the confidence. In the States, I was just like, “I know I’m not good enough to be a rock star,” and in the Netherlands, I felt like, “I can be who I am here, at this level. I have something to give.” That’s another thing, I lived in New Orleans before I moved to the Netherlands and I was totally happy and satisfied to be a spectator of this amazing music. I felt like I didn’t have anything to offer that. But when I got to Amsterdam, I saw people kind of playing around, and singing in English and struggling with the American accent sometimes, and I felt like I could add to that. And then, I just kept getting gigs and encouragement.

What was your first experience like, of taking your guitar out on the street and just starting to play?

It was weird. It was lonely, because I wasn’t playing for an audience that was there to listen to music, I was asking people to be there with me. I was able to get into what I was doing by myself, and then I’d come out of it in moments, when somebody would look at me and drop some money, and smile and touch their heart. That was actually huge. It can feel even bigger than being on stage, because of those individual connections.

I was traveling around the south of France busking, and most of these people don’t even understand the lyrics, yet they still want a hug when I come off of my little spot, and the children are dancing. Somebody wrote a note to me saying, “I don’t understand how people can just walk by.” Those are important moments… ‘cause I need reminding. I’m a leaky bucket, I constantly need to be reassured that I’m useful. And busking, playing on the streets, was jet fuel.

And it also works the other way around. You have these moments where people don’t seem to care… But that’s not what I’m reaching out for. I’m not playing to them.

Do you still busk? What for you is the difference between busking and playing on a stage?

The busking challenges you because you don’t know what’s going to happen – with the weather, with the people, with your equipment, with your energy. It’s a bit exciting and a bit scary. I tend not to busk where I live. When I first came to Amsterdam, I busked a lot. Then, once it became my community, I didn’t.

It’s a funny thing, I go in there with this pre-made shame. Because people have a certain definition of buskers. I don’t want to be “Lake the busker.”

What does that mean to you?

Some definitions float around in my head, like: you can’t get a stage, so you play on the streets. Which is really bullshit! There’s something very liberating about playing on the streets. And, quite often the reason you can’t get a stage is that venues don’t want to pay. It’s not about even about payment, it’s about respect. It’s about showing you that you have value. And you have to be able to get the types of stages that you want, because it’s like, you’re not going to get certain stages if you don’t play covers. So, when you busk, the street becomes your stage, it’s DIY, it’s squatting, it’s a kind of revolutionary movement – revolutionary for yourself, I mean. Busking’s not really changing the world! (laughs)

It can be a beautiful thing, because it’s all yours. You just made the stage and you have to have a lot of confidence in yourself, so that’s already empowering. You created the space.

Tell me more about how you create that space.

The choice of the space is so important. I don’t busk in front of terraces – sit-down cafes, you know? I want to find a place that people can choose to stop, they have the space to stop, or they can listen from afar. I was busking one time in Amsterdam – and this is another one of those great moments – and after I’d been playing for a while, somebody came from way around the corner, and dropped a lot of money in my case. I stopped playing and was like, “Woah, you didn’t even listen!” (Because always in the background for me, it’s not about the money, it’s about sharing something. I’ve had so many great moments of hearing music when I needed to, so what I’m doing is like giving an offering.) And she said, “No, I’ve been listening to you for quite a while from around the corner.” That’s the thing, too… to find out how far you can reach. So, I’ll never stop busking.

I haven’t done it in a while but that’s not because of shame. It’s also a lot of hard work, because I don’t busk acoustic, I have equipment. I always want to be a bit amplified. That’s something that makes your stage, and makes your atmosphere. I want a sphere, and I’m the creator of that. It’s all down to me, and I take that responsibility by having a really good mic and a really good little acoustic amp. Living in Edinburgh, and the Netherlands as well, you never know about the weather, so usually when I’m busking it’s going to be in France, or somewhere that’s more conducive to that.

It becomes an adventure, you know? When I’m travelling, it’s my good way to go fishing for adventures. Someone will say, “Come over when you’re done busking, come for dinner.” Again, it’s connection, connection, connection.

I do want to get back to something you said, which is about the relationship between money and your music. What is it like making your living as a singer/songwriter?

That’s really the hardest thing. It gets tiresome for me to have to talk about money all the time, even though I’ve learned confidence in saying, “Look, I’m worth this, and you can take it or leave it.” Because it’s a sliding scale, as well. It depends on the budget of the place, it depends on what it means that I play a gig. I played a couple weeks ago for a protest against immigration laws in the UK. But to be constantly talking about money is hard, and I have to be careful also not to get angry. I had a conversation with someone recently who asked me to play a gig, and they said, “Play here, you’ll love it!” and money doesn’t come up. Quite often, usually when it’s a free gig, money doesn’t come up. And I say, “You’re asking me to work. What is the recompense for my work?” And, they say: “Oh, as many beers as you want!”

That’s another thing, I don’t think that alcohol is a very respectable offer. This is something that’s happened throughout history, especially to black musicians, jazz musicians, where musicians have been offered alcohol instead of money. My granddad was a great trumpet player – he played with Miles Davis in St. Louis – and he became an alcoholic. I believe, the family believes, it’s because of that. A great musician and he became this bumbling alcoholic who could barely talk.

It’s weird how they don’t want to give you money, because what you’re doing is “not a job” – you love it too much. People bring themselves up, too. “I’d love to do that, but I decided to run a bar instead. Sell alcohol.” How is that any better for our community?

It’s a struggle. There’s also a lot of people willing to do that for free. That’s something we’ve talked about before: With a lot of these arts, it’s easy to get to the first level. Photography, as well. Go to any little charity shop, buy a guitar, or get a good camera. And do kind of well at the first level, and still be an architect. You can still…

Keep your day job.

Keep your day job, yes! So, musicians who decide to strive to get to the second or third level have a harder time. ‘Cause it’s a huge step. You know, first level – boom, it’s easy. Second level, you gotta fuckin’ climb, you gotta take time, you gotta spend money, and you gotta be there. I mean, that’s another thing about being a working musician, is that I’m available, and my availability has to be valued as well. I still feel like I’m just halfway towards that second step of skill level, but I’m certainly professional. Because you do also have to compare yourself to what’s out there.

What is that second level, do you think?

I wonder if I knew it by name, if I could get to it more easily. Then I could set the goal. Like, I could play the Doridian scale in 3/4 time. But really, I think it more has to do with this mysterious flow that I do find sometimes. The ability to access my skill quickly, without needing to fucking burn candles, and have the perfect situation and have people caring. But just be able to access it. I mean, improv is something special. And, writing. I feel that the depth of my writing hasn’t quite broken that film. I haven’t broken to the next level. Maybe that’s not the second level… maybe I’ve made it to the second level. What I do is already hard. There’s constant confirmation of that. Whatever level I’m at, I constantly feel like I’m this bumbling baby.

That sounds like part of your own self-criticism, though. I think you’re hard on yourself indefinitely, or as a character feature, and not necessarily for any good reason aside from some internal need to master something. You’re committed to producing something “good,” as opposed to just being satisfied with where you are. As you said, you are a professional musician, meaning you take your work and your craftsmanship and performance seriously.

I guess the thing is, I know behind the scenes that I have not worked hard enough. There’s a system of severe checks and balances that I got going on, and I’m happy for it because… I have seen people who think that they’re great, and they’re not. I guess there’s that fear of going out there with something that’s no good. I feel like I’ve got good taste, and I put my good taste up against what I do, and it never lives up to it. So, what do you do about that? Do you just quit?

If you’re a craftsman, you try to close the gap. Knowing that the high standards that you hold yourself to are good for your improvement but perhaps always by nature unreachable. And not beat yourself up too much about it.

Yeah, it should be hope, rather than optimism or pessimism. I guess I do fear being optimistic.

What do you mean about that?

Well, optimism is actually just the opposite side of the same coin as pessimism: everything is fine, so do nothing. Hope is: I see the good, I see the bad, and I believe in the goals that I’m setting. There’s goodness, but I’m aware that there’s a “bad” out there – the bad side of it, or the bad side of me. I can face that and be ready to try and reach my goals. If I’m actively putting myself down, and trying to thicken my skin up… maybe my optimism and pessimism will just cancel themselves out. Hope is what I’m striving for.

To what extent do you feel that your being hard on yourself helps you? That it keeps you honest or that it promotes quality or development in you? And to what extent do you feel that it holds you back?

I do see it mostly holding me back. Because it dips into my confidence, starts robbing it. I do believe though, that I should hold myself accountable for, say, not practicing or for choosing a bad gig that doesn’t support me or my work. I feel penitent. I wonder if it’s a Christian thing. Growing up with all that guilt. I wasn’t even Catholic. But I just know that I’m a person that’s prone to do wrong, and almost expect it.

Do you feel like that helps you in your process or is it just self-flagellation?

No, I don’t. I don’t feel like it helps, no.

But I know that there has to be some sort of check there. I’ve been working with another musician, Cera, and she helps me out of that. She gets angry if she overhears me in a conversation being hard on myself. I get these moments when I look at my guitar and I get angry. Before I even grab it to practice, I just get angry. Confidence has got to be the driver. You have to have confidence that you’re going to learn, to move closer your skill goal. Even before you pick up the instrument.

I still believe there’s a healthy check you can make on yourself: Was that a good gig? What can I do to improve? There are things to improve, let’s get on it. Don’t think that you’re set here. Don’t stop practicing. Don’t think you’ve just made a fuckin’ million-dollar song.

But then it sneaks in, because it’s already in your body, in your psyche. It sneaks in like a Trojan horse and starts robbing the healthy parts of you, and your confidence. And actually, I get kind of high on it sometimes, self-flagellation. I think people do.

How so?

Oh man, you know The Artist’s Way, right? Everybody does. There’s this part where she asks you to free-flow. You write down a sentence, like “I, Lake Montgomery, am a talented and creative fill-in-the-blank… musician.” And then you write down the first things that come to your mind when you say that sentence. And when I did that, I just got into a tornado of… it’s horrible. It’s almost like I blacked out… It was really scary, I was just making fun of myself. Really gettin’ in there.

What is it that gets you high on one part of you trying to destroy another part?

Well, that’s it! (laughs) I never thought of it like that, but that’s exactly it, it’s a part of me trying to destroy another part. There is adrenaline in anger, in rage. It’s a feel-good chemical. I feel clever, when I can make fun of myself. And it also hardens me, prepares me, just in case somebody else wants to do it. Like, I got to me first.

I do think there is a part of the psyche that feels empowered when it can harm itself better than any critic can.

Well, it can at least have you feeling weatherproofed against storms.

I thicken my own skin that way. But you know, when it runs off into a loop that can’t be stopped, that can be very detrimental to what you’re trying to do. It’s bright days and it’s dark days. And it’s great to have communities because they’re the ones that help me out of it. It’s not that I need to have people gushing, because I also have this voice in my head that says, “They’re just happy to see a black American singing, and feel authenticated.” People who like my music might like other music that I don’t care for, so how does that mean I’m any good? You know, what is “good?” But what lifts me up is when people come to me and give me evidence that I am a part of the community. That I’m helping.

Did I ever tell you the story about the guy in a beanie who came up to me after a gig and bought my CD? It was a good gig, I was feeling good about it, I was feeling a little sassy, so I said something about his glasses. He had these thick glasses, and one of the lenses of his glasses was halfway blurred out. I thought that was weird, so I said that to him. And he proceeded to explain to me in very slow speech that he had been a light technician in a theatre, and one day he fell from the rafters. It was very bad accident, his brains came out of his skull, and this is the state that he’s in now. He sees double. He was wearing a beanie, which I thought was just a fashion beanie, but it turns out that it’s actually a helmet because he still had a hole in his head. He took off his beanie and showed me the part of his skull that just had skin over it, and he said, “Any little bump can kill me.” He said he was very depressed about what had happened to him, and he’d had tons of operations to save his life. He said that his cousin found out that I was playing, so they travelled a good hour or two to come to my gig. His cousin remembered that he really liked my music, he didn’t remember – because he couldn’t – and he said to me, the doctors keep my body alive, but I need you to keep my spirit alive. You feed my spirit.

That was one of those big fuckin’ moments. BOOM. I’ll never forget that. Because I could see: This is good. What I’m doing is good. I’m helping, I’m not hurting. I’m not jacking off my ego. This is not vanity.

There’s a lot of people who don’t understand that art is something that’s woven into the fabric of the community to strengthen it – or it can be. So when I get reminded of that… that’s what matters. To really be reminded that what I’m doing is feeding, or nurturing the community’s souls. Helping spirits who need it.

That sounds like a really important thing to remind yourself of. I can’t imagine you get that kind of experience very often, though, so what do you do the rest of the time?

It would be great to be able to cultivate a voice that reminds me of those things. Every time I play a good gig, which I have to admit is most of the time, there are people who come up and say nice things. Obviously not that I’ve saved their life (laughs) but people come up and give me a hug, and ask how I’m doing. That’s caring. If that did not happen constantly I probably would not be here talking about music, because I wouldn’t be doing it. It’s a pretty big drop when someone comes up and has a story like that guy, but all the little drops for my leaky bucket do keep me out of the red. So, the trick really for me is to be constantly working. It’s a funny thing because there’s a part of me that wants to stop and not put anything out there until I get so much better, but then, I have to be able to sustain this. I have to constantly be out there, involved, and getting positive reinforcement.

It’s weird, though, because I’m not doing this for fame and glory. I don’t want to do it for myself, I want to be a vehicle. I want to be the vehicle through which speaks little whispers of God. You have these cliché responses like “Who cares what other people think?” but it’s not about that. It’s not because I want people to think that I’m cool or I’m pretty, but I do constantly need to know that I’m a working, useful part of society. That’s on the list of happiness criteria, right? People want to know that they’re giving something back, that they’re a part of that moving gift. Because that’s my economy. I don’t need much money, but I do need to know that I’m not worthless to my people.

What do you do on the days that you’re just not getting the right kind of feedback?

Oh man. Bad gigs set me back for weeks. And if I have a good gig, I’m up for about three days. (laughs)

How would you define the difference between a good and a bad gig?

It’s really knowing my own performance and then about feeling connected (or not) to the people. This is also why it’s really important to be careful about the gigs I say yes to. Let’s say a bad gig is at some pub where everyone’s drunk already because they put you on at 2 o’clock in the morning, and they just want entertainment. And they’re just like, “Sing something we know!” or “Sing something upbeat!” or “Sing some Tracy Chapman!” and there’s no connection, and it’s loud, and the sound system’s horrible.

That’s another thing, you’re completely fragile to the medium by which you’re putting something out there. If there’s a bad sound system, or people don’t care, that affects my performance, as well. The setup can throw me off and then, in the end, it’s me who does a bad performance because I’m affected. I’m very sensitive to those things, to an audience who is loud or just not in the mood for listening to my music, maybe the organizers were a bit rude to me. But it’s happened before, where I had what I considered to be a bad setup, and I don’t know what it is, maybe I had a good breakfast or I’m in a good mood, but I’m determined to do a good performance, and I do, and it can change the whole situation.

I had a gig in a little town in the Netherlands a couple of years ago for a birthday party, and everyone seemed so disinterested. So, I just did my best. When I was about to get off stage, they asked me to play longer, they were like “We’ll pay you more, just please keep playing,” which I thought was strange because what I could see was that they’re not into this – a couple people walked off in the middle of the song! There were people who were looking up at the ceiling, looking like they’re bored. And then I got off stage, and got a standing ovation from this little group of people, probably fifty of them. And in the hallway later, this woman grabbed my arm, and she said, “You had us all crying. Just overwhelmed with emotion.” And she was describing what she felt, which is funny because that’s not at all what I thought she felt. She was describing her deep connection to the words, and being overwhelmed with emotion, not sadness, but just feeling. She was saying she felt like she woke up. She said, “I had to look up at the ceiling in order to keep my tears from falling.” She said everybody was crying, and, “A couple of friends of mine had to go outside.”

You know, it was so funny because, again, I needed the reminding. At least I got the confidence to do my best, and to feel like, “If they like it, that’s fine, if they don’t, that’s fine. At least I know that I did my best.”

So, it really begins and ends with me. And that’s a good side of taking responsibility – straighten up, strengthen up, be who you are. Don’t cower under vain requirements that you have. Make the space yours.

Considering that it’s not your ambition to be a “rock star,” what would it mean to you to be truly successful?

I’d feel successful if I had produced a good legacy of work. And definitely a part of that would be accessing people. Not a billion people, I actually feel like that’s not natural. I know that art, and my art especially, is not going to be right for everyone. So, I don’t have that as a goal, to be right for everybody. I feel like I would have to lose a lot of the richness and the detail that’s unique to me. I wouldn’t find that art, I’d find that entertainment.

If someone was waving a million bucks in front of my face, and said, “Here, write one stupid catchy song, we’ll put a badass beat to it, you’ll make a million bucks and live the rest of your life on it,” … I wonder if I’d say no. (laughs) Maybe I wouldn’t tell my friends.

I’m sure someone like Beyoncé can feel proud of her work. She’s got a team of 100 people or more behind her work, and a lot of money behind her work, and I don’t mean to put that down, but I’m too simple – and I’m not saying that’s not a bad thing. I’m very glad to be simple. I don’t want to do that kind of stuff and I don’t consider it art.

Is that something that you’ve connected in your own mind: if there’s commerce involved, then it’s not art?

Huge amounts of commerce, to me, is not art. I do believe that that’s more business and marketing. I’m not saying I wouldn’t love to be rich, but let’s say, I feel like I know what humans do. And I know that a million bucks a day is not natural. It costs big money to push music, it costs big money to fly someone around, and get them in their element, and have their song coach, and have the radios paid off… it’s just too much. It’s so heavily funded and produced, and it’s not individualistic. There are huge teams of people working to make large amounts of money. It must be money-driven. Must be. And sure, it’s fun, I’m not saying that it’s a horrible thing… But, honestly I wouldn’t mind if it didn’t exist.

Art to me is something that moves me. That connects me to the artist.

Is there something that you fundamentally feel disconnected from, the bigger it is?

Yeah. They go for what is tried and true. A lot of money goes to market research and what beats sound good. It seems to me all numbers, catchy songs, lyrics – God the lyrics! So empty.

I like finding little pieces of gold under a rock. You can say that also satisfies that hunter/gatherer part of me… people love to discover something small and beautiful, and that makes them feel like a part of it, as well.

Anais Mitchell is somebody I consider successful. Her work is amazing, moving. She plays gigs in a venue of, say, 200 capacity. It’s all she needs. She has a legacy of work behind her already. And I’m sure she’s not making a million bucks, and she’s not a rock star… but she’s making it work. And I believe that she will be a legend. Her work will never die with her because it’s good, it’s solid.

I do always encounter problems with this idea though that there’s something noble about being poor, or that if you accept money for something, it’s somehow “tainted.” And I think a lot of artists have this limiting belief, myself included to some extent. I don’t know if there is a right answer, but I do hear it when you’re speaking, and I’m wondering to what extent would you feel comfortable with someone offering to pay you a million dollars for your music.

I just don’t think it’s that easy. When I say this ‘million bucks’ thing, it’s loaded. It’s symbolic of the whole industry going way too far. It’s mixed up with marketing and selling children images and dreams and fantasies and stereotypes. You see a music video that cost a million bucks to produce and I don’t feel connected to it. It’s just my personal experience and my perspective. Maybe some people do feel ultra-connected to this type of media entertainment.

I do require money. It is a big part of what I do. And it is one of the more universal and accepted ways for someone to represent that they see value in what you do.

One of the weirdest things that I find over and over again: If there’s a gig that doesn’t pay, I would expect to be shown that they value what I do in other ways, like kindness, or making a space for me to sit down and tune my guitar and get into my head before my gig – any of that. And on the contrary, you get to a gig that that pays little or nothing, which you’ve accepted for whatever reason, and you get treated like shit. And gigs where they’re paying me 300-400 euros, they’ll treat me like a queen, because they know what they’re paying for. Play some gig for a pittance, and they treat you like the monkey they just threw peanuts at. Constantly.

There’s so many reasons to keep your prices respectable. It’s out of respect to yourself, it’s a guarantee that you’ll get treated well – that’s still something I have trouble understanding or explaining. But that’s something you have to deal with all the time. Everybody starts to get a thick skin – the organizers, the bar owners, the artists, the bartenders, the people…

And it gets harder to make a connection with a thick skin.

Yes, it gets harder to make a connection with a thick skin – that’s it. So, really, another practice that you have to do, you gotta constantly be exfoliating. And be brave on the inside.

Going back to that self-loathing – it’s not brave. That practice of self-loathing is just to thicken my skin and to be ready for that harsh world. But the practice of cultivating your confidence and appreciating and loving what you’ve already done and who you are right now, and cultivating that hope and confidence that you’re on the right path, that you are connecting to people and that you are getting better, you are honing your craft… that’s something that you have to constantly protect. It’s a timid little beast.

When we spoke the other day, you were saying how performing on stage was the place you could always get it done, because there’s no escape. Tell me more about that experience.

The stage is the place. I feel like I step into a different world. And if I can really be there, and not get pulled out of it by whatever distractions, then I can find that flow, and it doesn’t matter what’s off-stage anymore because I’m in this world now. Sometimes I’ll come out of the song and not know where I am. Like, what, people clapping? Oh, yeah, I’m on stage.

And it’s mixed with the hard fact that you’re on a stage, you are here to do what you’re going to do, now. Now is the moment. There’s no ‘out’ and also there’s the fact that you’ve created your space. No one can enter. This is my safe space. Of course, I don’t tell myself these things before getting on stage, these are just like millisecond facts that I’m aware of, that make me get up there and just get it done. But it is stepping into a different sphere. I go high.

When you’re on stage, you’re pulling this energy from somewhere that you don’t pull from offstage. I can come off stage and be so exhausted, in a good way even. The better the gig, the more exhausted. I can feel like: God, I just did my work, and I pulled from every bit of me to do it.

I know you’re not yet where you want to be, but given that you’ve already made a lot of growth on your own path, what wisdom would you want to impart on the younger version of you?

Seek out communities. Don’t be afraid of embarrassing yourself. As much as I’ve been able to connect with people, I can look back and still say that I could’ve connected more. There’s a lot of offers that I’ve gotten, which, because of my lack of confidence, I put off. I’d say to myself, “I’m not as good as they think I am, so I’m just going to ignore this offer.”

There’s a huge procrastination that’s been following me around in my life. It’s always because I thought I wasn’t good enough yet. The thing is, if you think you’re not good enough, then go through the steps of making yourself better. But don’t black out the present you. Don’t ignore the work you’re doing and the people who are around who want to be part of it. Just be involved and take responsibility for your growing talent.