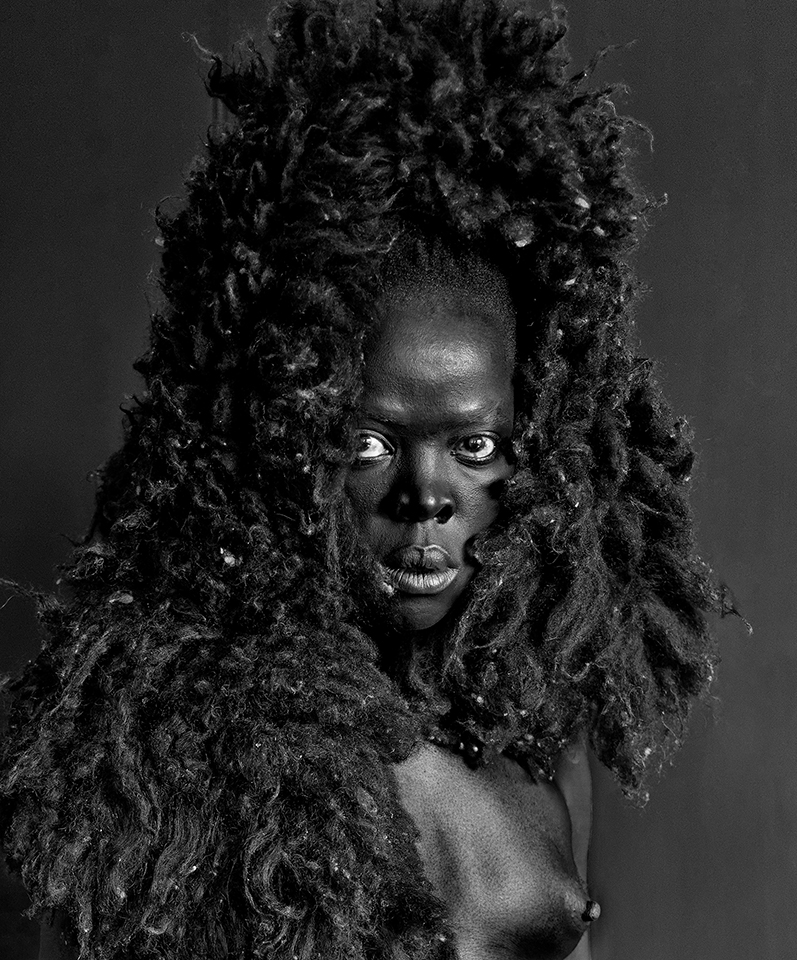

In the photobook Somnyama Ngonyama, South African visual activist Zanele Muholi creates an identity, performs an identity, dismantles an identity, confronts with identity.

Move Fast and Break Things: An Interview with Jonathan Taplin

Jonathan Taplin is the author of Move Fast and Break Things: How Facebook, Google, and Amazon Cornered Culture and Undermined Democracy, a book about the formation and rise of new technology companies with libertarian ideologies. Focusing on three monopolistic technogiants—Facebook, Google, and Amazon—he argues that they’ve become engines for increasing inequality. The revenues are colossal, yet they employ few people in comparison to normal companies. He speaks with us in this interview about surveillance capitalism and the dubious notion that disruption is a moral good.

Your book’s subtitle neatly summarizes your argument: How Facebook, Google and Amazon Have Cornered Culture and Undermined Democracy. How did this happen?

The basic thesis is that the internet was originally conceived as a decentralized medium, but starting in the late eighties, a few people—Jeff Bezos of Amazon, Larry Page of Google, Peter Thiel, who was an investor in Facebook—came at the world from a very libertarian point of view. They understood that the internet could be a winner-takes-all business. They set out to create that, so there would be a need for only one search engine (Google), a need for only one e-commerce portal (Amazon) and eventually a need for only one social media giant (Facebook). Essentially, they’ve accomplished that.

My argument is that this has been bad for culture, bad for musicians and artists, and bad for democracy.

And we allowed this to happen?

There is very little regulation. Amazon didn’t have to pay taxes on internet sales, so they could put four thousand independent bookstores out of business. YouTube didn’t have to respect copyright, so they could take anything from anybody without paying for it. And, ultimately, they didn’t have to worry about a monopoly, because regulators around the world let them go ahead. At this point, Google has 90% market share in search advertising, Amazon has 75% of the books business, Facebook and its associated firms that it owns, Instagram and WhatsApp, have about 75% of the mobile/social business.

We have heard a lot about the democratizing effects of the internet, but you’re arguing that it’s undermining democracy.

As we saw in the American elections, these tools can be used to spread propaganda in a very targeted way that nobody really understood before. These companies have no obligation to try and decide whether anything is true or not. So it was very easy for Steve Bannon to put out the “Donald Trump is endorsed by the pope” story, and there was no way to stop it. If you hit it with enough bots, it could become the top searched item on Google and the top of Facebook’s trending topics. That became a pernicious way of undermining democracy, and nobody really is doing anything about it. There’s no real solution and no way I can tell who paid for the advertising in political campaigns.

Beyond that, there’s the whole issue of privacy. The notion that you have some level of personal privacy is pretty much eliminated by these companies; they know everything about you – where you go, what you buy, pretty much everything you do.

You write about the impact on musicians in particular. They now have the ability to reach their audiences directly, but you argue that YouTube has enveloped all business.

Youtube puts every song that exists in the world for free online, and then it goes to the music community, and says, “Look, your content is going to be on YouTube whether you want it to or not, so the only decision you have to make is, do you want some advertising money or not?” And, let’s just say that you had a huge hit single. If it was downloaded a million times on iTunes, you could make $900,000. If it was streamed a million times on YouTube, you would make $900. That’s not enough to pay my rent in Amsterdam, even with a hit song.

The proposition that YouTube is making is closer to a mafia extortion racket than to a fair deal between a willing buyer and seller. YouTube is a cynical organization that makes its decisions basically on what it can get away with.

Do you see the way out of this?

I have a fairly optimistic view of where this all can go – with a little regulation. We need to re-de-centralize the web. There’s no reason why it has to be the way it is today. If Facebook had to compete with WhatsApp and Instagram, maybe one of them would offer you a better deal – not take so much of your data and give you what you want. You know, not be in the surveillance capitalism business.

There are many positive aspects. The very fact that people are spending $10 a month on Netflix, which then allows Netflix to spend $8 billion a year on content, is a positive thing. So, I’m not a Luddite by any means, I’m just saying that we have a kind of a techno-determinism in which we cede the future to the people who run these companies. We think they know what they’re doing.

Google wants all trucks to be self-driving. Well, there are 5 million people in the US who drive trucks for a living. Google has no idea what to do with those people. They’re not planning to hire them as coders, these are 50-year-old working class people without college educations; they’re just going to be put out of work. There’s no politician in the world who’s got a plan for what to do with that, and yet it’s coming. Fast.

The title ‘Move Fast and Break Things’ echoes the rock ’n’ roll mantra of ‘Live Fast, Die Young’. How do these two industries, tech and rock, match up?

Obviously, the title is there with a great deal of irony. The notion that disruption is the highest form of behavior in tech culture is, to me, sad. It’s fine to disrupt the news business, if you replace it with something else. But Facebook is not interested in bringing the local news to Nashville, Tennessee, they basically just kill the local newspaper.

If you think that disruption is the highest calling – you know, move fast and break things – you have to rethink things. Friction has a role to play. It makes you slow down and think about things. And that’s all I’m really saying: we need to think about this.

This interview was originally published by John Adams Institute as Jonathan Taplin came to speak in Amsterdam on Feb 2, 2018.

This interview was originally published by John Adams Institute as Jonathan Taplin came to speak in Amsterdam on Feb 2, 2018.