"There are definitely days when I don’t have the energy, and today is a day I’m struggling. [...] It really is fighting every day and the project gives me something to fight for in a productive way that’s bigger than myself, which seems to be good for me."—Tara Wray, in our interview about the Too Tired Project.

Virgin Territory: Discovering the Unknown Reveling in the act of discovery at Unseen Amsterdam

Ancient maps marked the accomplishments of discoverers, documenting the world as known thus far, the boundaries of which were marked by monsters: “Here be dragons.” Modes of discovery have changed—we may now brag about being the first to hear of a new band, or the first to develop some kind of app—yet the impulse to realize the unknown remains hard-coded somewhere in our humanity. Artists, too, bear the desire to discover as yet unexpressed ideas or emotions. And curators, publishers, and others of the art world hungrily seek to discover new artists and put them on the map.

At Unseen Amsterdam, an annual photo fair and festival set in late September, we see on full display the playing out of this urge to discover. Unseen specifically aims at showing—unsurprisingly—“unseen” photography, whether work by new artists or simply new photographs from established artists. While some other fairs and festivals may curate according to a theme, or allow galleries to bring whatever they think is most saleable that season, Unseen Amsterdam tries to position itself at the edge of the photo world in terms of content. To what extent you experience the art on display as unseen depends on how proximate you are yourself to that edge. For example, Pixy Liao’s beautiful work Experimental Relationship has just been released as a photobook, and so was being presented this year by a gallery—however, the work is already rather older than that. I first encountered and published the series on GUP Magazine in 2014. (Do you see what I did there? I bragged about a discovery.)

Unseen Amsterdam is first and foremost a fair, which means that galleries come to present work that they believe will sell to the audience. But there are also peripheral exhibition spaces that allow for alternative views on photography. Futures, for example, is presented as “a new photography platform that draws from talent programmes of leading photography institutions across Europe.” Ten photographers from various European countries are showcased together, mainly as a means to offer support and exposure at an early stage in their career. Among them, I was particularly struck by the work of Berlin-based Yana Wernicke, whose work-in-progress Bombay Dream was on display.

Unseen Amsterdam is first and foremost a fair, which means that galleries come to present work that they believe will sell to the audience. But there are also peripheral exhibition spaces that allow for alternative views on photography. Futures, for example, is presented as “a new photography platform that draws from talent programmes of leading photography institutions across Europe.” Ten photographers from various European countries are showcased together, mainly as a means to offer support and exposure at an early stage in their career. Among them, I was particularly struck by the work of Berlin-based Yana Wernicke, whose work-in-progress Bombay Dream was on display.

Wernicke says that she was inspired to make her project after hearing of men and women moving to Mumbai to become actors and actresses. While Bollywood is a part of it, Wernicke clarifies that there’s a wide diversity of filmmaking going on. “Most of the women I [photographed] are doing the smaller jobs — like regional Marathi TV, commercials, theatre and online productions,” she says. “There is also an alternative film industry in Mumbai which produces movies that are not meant for mainstream audiences. For many of them, however, this is just a starting point and some of them do dream of being in a major movie one day.”

So, Wernicke is photographing women who hope to be “discovered,” and presenting these photos in a context in which she herself is in the process of being discovered.

It is in a sense absurd to think that one human can discover another, unless we want to talk about something perhaps a little sensitive and profound, in terms of coming to truly understand the uncharted depths of another. But often what we are in fact referring to are gatekeepers, those people who develop and cultivate proficiency in a field, who further define that field by the projects and people to whom they give attention. That is, because curators have cultivated taste, when they point us in the direction of an emerging artist, it matters to her career and to the way the public evaluates her work. When a casting director hires a young actress for a part, it matters, too. And yet, we as the external public never have any direct view on why any particular person was deemed worthy of being discovered, and what recompense may be taking place behind closed doors, consensual or otherwise.

It is reasonable to wonder why discovery—if such a thing even exists—occupies such a prominent status in our collective imagination.

In the case of India, Wernicke says that, “it is still mostly men working in and producing these films. I remember when I joined a set for a regional Marathi television show there were about 50 men on set and maybe five women (who were the actresses and one make up artist).” This facilitates an environment in which men are positioned as gatekeepers, and women are positioned as accoutrements. In such environments, women are tasked with (and in unpleasant truth sometimes enjoy) playing the role of the damsel in distress, who greets her savior with gratefulness. It feeds the egoistic need of men to be the first, whether we’re talking about discovering land, finding new talent, inventing breakthrough technology, or claiming virginity. And yet, when it comes to the discovery of human beings, it’s often by necessity a two-person dance.

This is the codependent dysfunction of the discovery of human beings: that one person submits herself to the other for discovery so that she may be seen, while the discoverer is rewarded for making a map of something that was already plainly there.

Walking around a venue like Unseen Amsterdam, an articulated and curated space of “discoveries,” we all revel in ourselves. Gallerists bask in their ability to bring new work to the public, the public basks in their presence among the unseen art, the artists are glad to be seen. I’m among the revelers myself: I love the discovery of the unknown, and spending all my time in nebulous regions at the edge of the map with dragons.

So, is there anything fundamentally wrong with this shared love of discovery? Or is it win-win-win all the way around? Well, it depends. “You were working as a waitress in a cocktail bar when I met you,” sings the male role of the duet Don’t You Want Me by The Human League. “But don’t forget, it’s me who put you where you are now, and I can put you back down too.”

Discovery as an adventure is its own reward; for those who take pleasure in building out the map, we are all collectively wiser and richer. Where it takes a toxic turn is in the bald quid pro quo of discovery; for the gatekeeper seeking repayment, discovery is just the first part of the transaction.

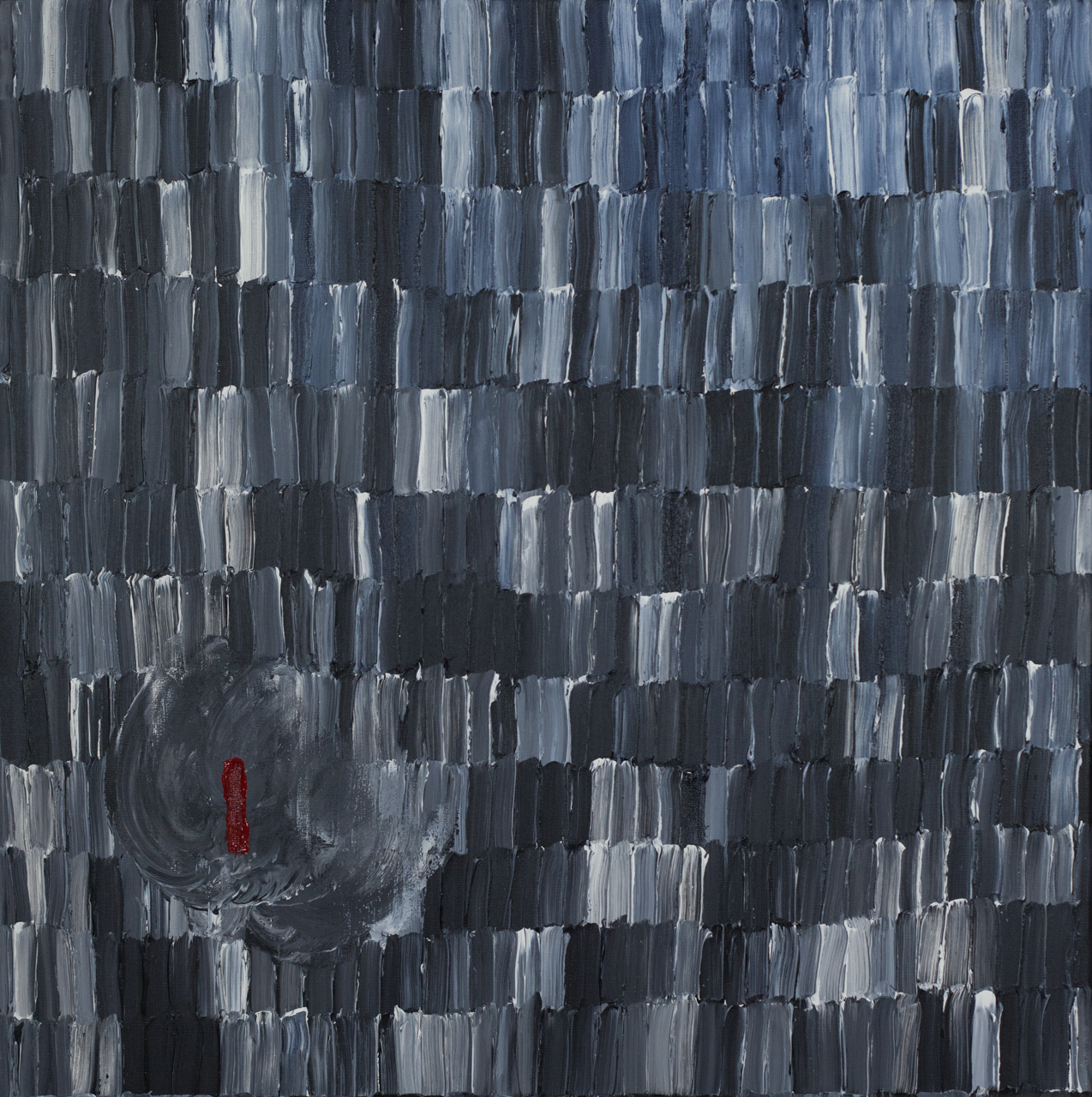

In Wernicke’s series of images, perhaps because she herself is a woman, her act of discovering these actresses seems imbued with the sensitivity of a shared journey. They are somehow peers, exploring the map together. The resulting images reveal curiosity and vulnerability. It is discovery freed of conquering.

Unseen Amsterdam is an annual photography festival in late September.

Bombay Dream is a work-in-progress. See more of Yana Wernicke’s work on her website.