Ancient maps marked the accomplishments of discoverers, documenting the world as known thus far, the…

Being Human Is a Team Sport A review of Douglas Rushkoff’s book Team Human

“We are increasingly depending on technologies built with the presumption of human inferiority and expendability,” writes Douglas Rushkoff in his new book, Team Human. Indeed, many trends of modern life—from automization that replaces human workers to algorithms in apps that track and even guide our real world behaviors—have trained us, he argues, to see our humanity not as a strength but as a liability. Given that Team Human is bound in a fire engine red cover adorned only with all-caps text, and written in impassioned, declarative sentences, there’s little wonder it’s being plugged as a “manifesto.”

“We are increasingly depending on technologies built with the presumption of human inferiority and expendability,” writes Douglas Rushkoff in his new book, Team Human. Indeed, many trends of modern life—from automization that replaces human workers to algorithms in apps that track and even guide our real world behaviors—have trained us, he argues, to see our humanity not as a strength but as a liability. Given that Team Human is bound in a fire engine red cover adorned only with all-caps text, and written in impassioned, declarative sentences, there’s little wonder it’s being plugged as a “manifesto.”

For those who follow Rushkoff’s podcast Team Human, the book’s ethos and content will be familiar. The podcast, which launched with Episode 1 on July 29, 2016, covers wide-ranging topics of human life, like technology, economy, education, politics, permaculture, and business. Likewise, in the book, he doesn’t limit his focus to a single aspect of our modern lives but rather tries to describe holistically how the systems in which we as a society live shape our beliefs and behaviors unseen. Formulated through one hundred focused micro-chapters, his argument urges a return to humanity, which is to say, that we must embrace and herald rather than mitigate or transcend the qualities that make us human, and, emphatically, that we must do so as a collective.

As he puts it: “We cannot be fully human alone.”

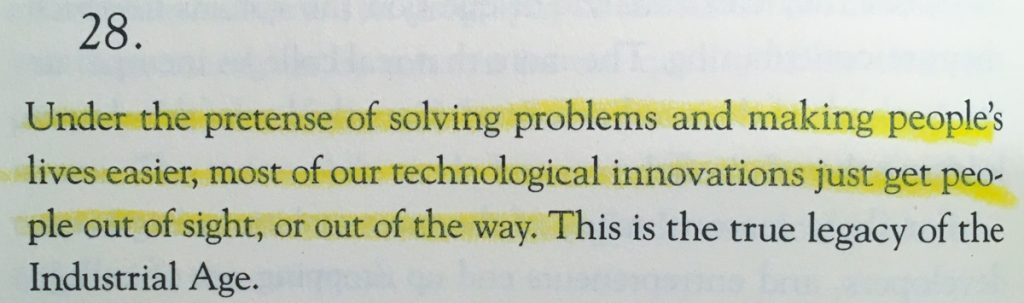

Rushkoff’s approach is systematic and utterly accessible: he distills complex ideas reached over time and much thought to sharp sentences that, when asserted in such a minimal fashion, appear on the page like common sense or rules of thumb you just hadn’t heard yet, but which surely have always been there. For example, “The highest ideal in an unrestrained digital environment is to transcend one’s humanity altogether.” Or take, “Art, at its best, mines the paradoxes that makes humans human.” And, “We must not accept any technology as the default solution for our problems. When we do, we end up trying to optimize ourselves for our machines, instead of optimizing our machines for us.” Dependent on whether you’ve arrived in your own lifetime to those same rules of thumb, or if they ring true when you encounter them, you may find yourself fired up together with Rushkoff or against him. The sentences don’t pause long enough to explain themselves, they bask only in their own self-evidence. It’s language stripped of uncertainty and ambiguity, which, I’m inclined to say with a smirk, makes it less human.

However, in a moral argument, there is typically little room for doubt: x is harmful and y is beneficial. Rushkoff is a humanist, and his essential moral assertion is that the systems we create must serve us, rather than the upside-down world in which we serve our systems. Whether we’re speaking of capitalism and marketplaces, media programming, AI, corporations or systems of government, they are all abstractions we’ve invented to better organize and understand life, whereas we are real. While we may find ourselves overwhelmed by or in awe of the capabilities of some of our inventions—how many of us who use Wi-Fi every day can explain how it works?—it’s critical to maintain the proper perspective regarding who is in command.

We can see in Rushkoff’s TED talk the same paradoxical tone that breathes through his writing: a seething anger for the human nature that got us into this mess married with an unrelenting optimism for the human nature that can pull us out of it. It is at once a scathing criticism and a lovesick plea for humanity to return to itself.

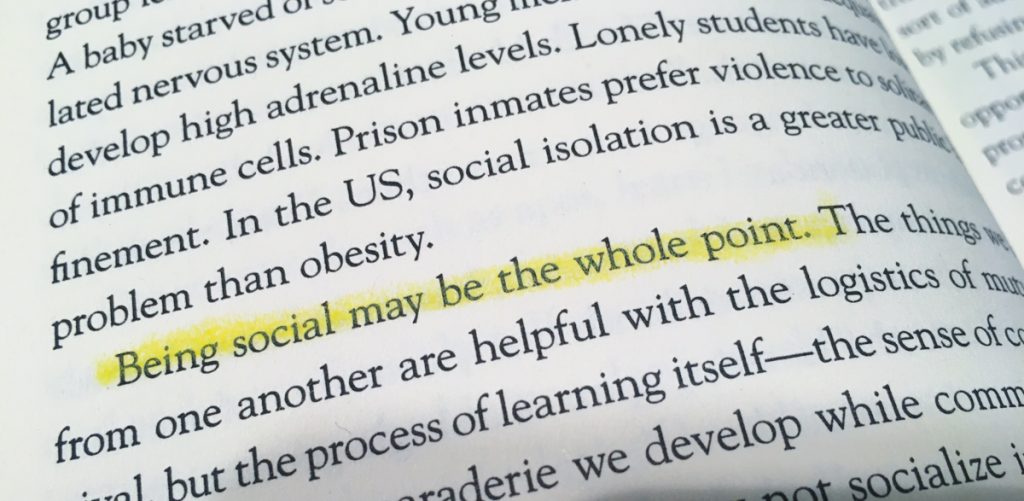

The key to our salvation is what Rushkoff identifies in his role as a sociologist: teamwork. However, rather than issuing a sentimental call for a group hug, he soberly walks us through the “invention” of the individual, and the importance of this concept in understanding ourselves as distinct from the societies to which we belong. “The key to experiencing one’s individuality,” he writes, “is to perceive the way it is reflected in the whole and, in turn, resonate with something greater than oneself.” The awareness of both individuality and community is what enables us to relate to both with more intentionality. We can choose to come together. When we use our human gifts of communication and collaboration, we are empowered by our collective organization.

As a manifesto, Team Human leaves all of us culpable and redeemable. We are each potentially suicidal elements within the human race who, through our misanthropy and mechanomorphism help systems, nature, and technology bury us all. And, we are each potentially cooperative components in the movement towards reclaiming ourselves and actively creating a desirable present and future reality. Far more than a single decision, to join Team Human involves many conscious choices. But where to even begin? For now, find the others.

Team Human has been published by W.W. Norton & Company. For more information on Douglas Rushkoff, see his website.

Team Human has been published by W.W. Norton & Company. For more information on Douglas Rushkoff, see his website.