"Even as a young girl, it was very obvious to me that my body - and the way people viewed my body - was going to be part of my experience as a human on this planet. "—Jamie Schofield Riva, in our interview on the power and scrutiny of beauty.

Values as Stars to Steer By A review of Well-Being as Value Fulfillment by Valerie Tiberius

Each life presents countless divergent possibilities, found in forking paths and the choices that lead us in one direction rather than another. The miracle of this, however, presents us with a quandary: “If there are a number of lives that are equally good, how can we identify a path forward?” asks philosopher Valerie Tiberius. “How do we know how to make things better if we don’t know precisely where we’re going?”

In her new book Well-Being as Value Fulfillment: How We Can Help Each Other to Live Well, Tiberius tries to address the question from the perspective of the well-being of others; that is, how we can help others in a meaningful way beyond dispensing advice, wringing our hands at their dilemmas, or walking away in frustration when—according to us—they just won’t help themselves. The argument she presents is that we must use values; our own values should guide our own behavior, and when helping others, we should try to do so from the perspective of that other person’s values.

We can clarify first with Tiberius’ definition: “Intuitively, values are things we care about, things that are important to us, things we organize and plan our lives around.” More concretely, “values are the projects, activities, relationships, and ideals that we value, and to value something in the fullest sense is to have a relatively stable pattern of emotional, motivational, and cognitive dispositions or tendencies toward what is valued.” This all sounds well and good, but as many of us have discovered during our lifetimes, there is such a thing as an unhealthy valuation. We can for example value two things which conflict with each other, such as having a stable marriage and a flourishing sex life with new and interesting people. We can also value things which seem to us the best option, such as steady paycheck at an unfulfilling job, but are in a more complete picture leading us toward unhappiness and an emotional undoing. In short, we can have “defective desires.” These are the types of observations that we can perhaps more readily observe from the outside, when we witness our friends wrecking themselves, their future, or their loved ones. This sticky situation of observing our friends in distress and wanting to be of help but also cognizant of the pitfalls of doing so is where Tiberius unpacks her argument of values fulfillment.

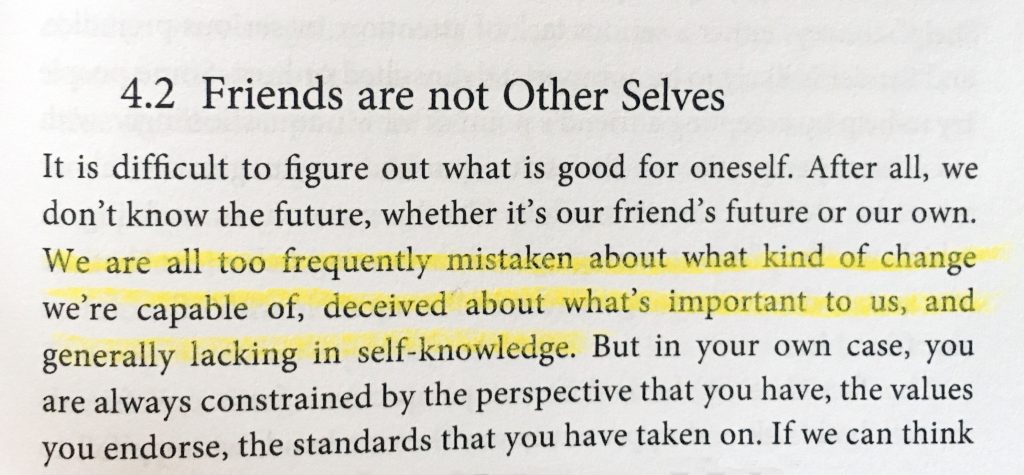

One of the main issues is quite simply that other people are not us, though we intuitively—and falsely—imagine that they are. When we imagine walking in another’s shoes, Tiberius writes, “one of the main barriers to accurate perspective-taking is a kind of self-focus or ‘egocentric bias’ that encourages us to think that other people’s shoes feel much the same as our own.” It is a faulty exercise to begin with because “you are instructed to think of what it would be like to be you in different circumstances, rather than thinking of what it would be like to be someone else in those circumstances.” We therefore bring our own values and circumstances to the equation, and propose a prospective reality which is not aligned with our friend’s present path. The outcome of this can be useless or even harmful. We must, to some extent, let go of the idea that we know what’s good for another person.

On the contrary, it is often our outsiders’ perspective which can be useful to another person, though this too has its limits when we overstep into believing it to be an objective perspective.

Tiberius brings us to what is likely a familiar and frustrating place: that often our role as helper may be essentially to listen. She prescribes humility, asserting that a properly humble friend is “inclined to be less self-focused, less self-satisfied, less certain about her own powers of observation, and disposed to question her assumptions about what other people are like and what they ought to do.” Yet it is in this space of quiet humility where good friends can do the real work of friendship: helping each other to figure out what to value and how. “They can do this by illuminating conflicts in a friend’s system of values, pointing out ways that those values could be better pursued, and by using their own point of view to help envision a value-fulfilled life that is within reach for their friend.”

Though Tiberius does not make the inverse statement, about how we might best receive this help from friends, it seems apparent too: we should allow our caring friends to shine a light on our conflicts, to introduce us to other possibilities, and to help us imagine a life better lived.

Well-Being as Value Fulfillment is a pensive look at the fraught topic of helping our friends—a topic so quotidian that it would be at home on a flyer in the waiting room of a doctor’s office. Yet Tiberius expounds on the complexity that often leaves us mired in conflicts as we try to help—and fail. She explains with sensitivity and verbosity the importance of coming to understand what matters to ourselves and others, and being alert enough to respect the difference between the two.

Well-Being as Value Fulfillment: How We Can Help Each Other to Live Well is published by Oxford University Press.

Well-Being as Value Fulfillment: How We Can Help Each Other to Live Well is published by Oxford University Press.