In her new book Everything Happens for a Reason, divinity professor Kate Bowler writes openly about her own confrontation with death, and how this fits in with the prosperity gospel.

Working Through Loss: An Interview with Photographer Alicja Dobrucka

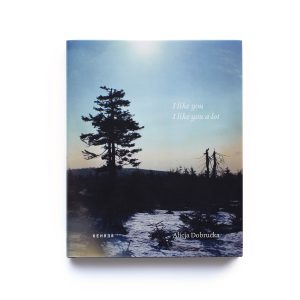

Alicja Dobrucka’s photobook I like you, I like you a lot, published in 2019 by Kehrer Verlag, was many years in the making: It began following the death of her younger brother Maks, who drowned in 2008 at the age of 13 during a scout trip. The photographs and editing continued to evolve for the next decade, together with her feelings on the event and its aftermath. Yet, as Dobrucka explains in this interview, even though her artistic energy was also poured into other, unrelated projects over this time, it’s impossible to understand her way of seeing the world without considering this underlying and penetrating truth of her life. In this conversation, she speaks on the grief behind her brother’s death, the translation of emotion into work, and how the project shaped her as an artist and a person.

You and I first talked about this project, I like you, I like you a lot, several years ago. So, it’s something that you’ve been already presenting and including as part of your body of work for a while now, but the book has just been released. Can you tell us a bit of the history behind the project?

Yes, that was years ago. I was doing my MA in London when my brother died, and I started working on this. I was on my own little planet making this thing, and I thought, “Well, I better quit.” Luckily, all the tutors understood that I couldn’t do anything else, and accepted it as my MA work, and so I carried on. It really helped me and shaped this work, the fact that I was at this institution and the fact that there were people around who could recognize what was happening—because it was never really meant to be shown, the work I was producing at that time, it was purely for me. I wanted to have a proof, and to be able to understand that my brother has died, and that it has actually happened. So, it was shooting “into the drawer” for a very long time.

I started showing the work because of the MA final show and the context of all these opportunities that come when you graduate. The work was still in progress, and then, after university, I won the Deutsche Bank Award, which propelled it forward. I traveled to Poland now and again and worked on it some more, and in the meantime I’ve made other bodies of work, but this one has always been in the background and never finished, you know? I always thought I could do more, I thought I could keep coming back to Poland and carry on with it forever. It was an option to have this as a work-in-progress for life. For a long time I thought it might stay this way.

Why did it feel so unfinished?

Maybe because it’s about loss, and the loss and trauma and feelings when someone young dies is really shocking. It’s hard to make head or tails out of anything.

Recently, I’m renewing friendships and relationships with people that I haven’t seen for a long time, and I just had lunch with a woman who was in a car accident last year. She’s still going through operations and things, and it’s still kind of sinking in. It was the first time that I saw somebody that was living through a trauma, and everything that comes with it. When she talked about her condition and what she’s going through, I noticed how removed she was, how factual and slow.

Likewise, I think I was just in shock for a very long time. I remember showing the work to someone back then, and she said to me, “This is so hard, this is so tough,” and I said, “No, it’s alright, I’m working on it.” I was hiding the fact that I was unwell. She said to me later that she then understood how deeply upset I was—because I was trying to hide it.

When did it change for you and become “a work” rather than just for the drawer?

With the final show for the MA, because I needed to show something to graduate and to apply for various things. Somehow it pulled me together. I was able to articulate it a bit more. Then the work was exhibited at the New Contemporaries, and then it was considered and welcomed in the art world as “a body of work.” I think this project made me an artist. Because there was a focus, there was one underlying theme.

I’ve always wanted to make it into a book, and I’ve spent years and years reshuffling it. The edit has changed drastically: When I showed it for the MA, I didn’t like the pictures, and none of those pictures ended up being a part of the work later on, so then I reworked it for the Deutsche Bank Award and made it into something else. It was really in pieces for a long time, even for me. Thinking back to it now, I did different things within this work, like at one point I tried to retrace the objects of my brother, and then I did some studio work which I then dismissed, because I wanted to give a formal quality to the book—a simplicity. I think the 2016 exhibition in Poland was the most finished, the most decided edit of that work. That made me think that this work was really worth editing at that point. Also, I made my last trip to my hometown, Kowary, Poland, and I noticed that I’m already focusing on other things. When I revisited the subjects of the book—hanging out with the boys who were friends with Maks, and retracing the objects, and spending time there—somehow it doesn’t resonate. I started working on another thing, which is a movie, and I noticed it’s no longer in me to carry on this work.

Given that this project is so intermingled with your person—you mentioned not only that it helped to pull you together but also that it made you an artist—what do you think is represented here: Alicja the person or Alicja the artist? What’s in the unfolding?

I think it’s both. There are a lot of landscapes and architecture in the work, which you can see in my later bodies of work, where I look at Palestine and Mumbai, for example, on topics that are external to me. I made this work—I like you, I like you a lot—with a smaller camera, for a discreet way of making the image, to be kind of unnoticeable, invisible. In the later series, I changed cameras to suit the need. The work from India—Life Is on a New High—was a very well thought through way of working; the format was set up, the vantage point was similar across all the imagery. The same with the Palestinian series, Houses (31°23′30.67″N 35°6′44.45″E).

With this one, I’ve gone all over the map. It’s a mishmash of little things and dark landscapes and the work is kind of documentary but a non-documentary at the same time. There’s a lot of landscapes and accidental things that come into being. It’s not purely a trauma documentary about the loss of my brother, it has become something else by being so polished and so much time having passed.

Does it feel “done” to you now?

(laughs, and takes a long pause) Yes. It feels like a chapter has been closed, and now there is this thing that I can look at. It’s very nice to have things that are physical in the world, because that’s when you as an artist or photographer decide what it is that you want to put out, and if you manage to finalize something in a book, it becomes eternal in a way.

I’ve just been in the darkroom all weekend, so I’m thinking about how behind I am with my printing, and it makes me realize: if I died tomorrow, nobody would be able to go into my archive and pick out what I would pick out and how. I was thinking of the story of the Met museum releasing the entire archive of Walker Evans online. Now any curator can take it and choose a selection, and make it into something new. That’s something different, do you know what I mean? When you make something physical, it’s defined. It’s you saying that’s what the work is; that’s the edit.

But, does it feel closed to me, now? (laughs) Maybe I’ll always be a bit too close to this work. But yes, it is closed. And I think it’s closed in a nice way, too, a kind of “family” way. A family company printed it, and the opening text was written by my best friend, Thomas Frangenberg, who actually died during the production of the book, and then another text was written by my good friend and someone who I work with sometimes, Olivier Richon. So, it’s done, and all of it done in this nice, friendly manner.

How do you feel about it, now that it’s done?

This work is important for me as an artist. It was very important to have this one resolved and closed. I always thought my first book would be Life Is on a New High, because it was easier to edit, but in the end, I just couldn’t not have had this work resolved and out in the world. Because I feel that it will be very difficult to understand me as an artist if you don’t know this work. You can see not only my personal story but also my context, where I come from and this kind of intrinsic Polish-ness. It’s biographical.

This work is important for me as an artist. It was very important to have this one resolved and closed. I always thought my first book would be Life Is on a New High, because it was easier to edit, but in the end, I just couldn’t not have had this work resolved and out in the world. Because I feel that it will be very difficult to understand me as an artist if you don’t know this work. You can see not only my personal story but also my context, where I come from and this kind of intrinsic Polish-ness. It’s biographical.

This work happened because I had my friend’s camera and my dad said, “Alicja, come in and take a picture.” My dad was called in to identify the body, and he fell apart, and he called me and my mum inside and asked me to take a picture. For him it was normal to take a picture, because he used to photograph everything—weddings, funerals—in the small village he came from. That’s what we photograph. It’s this kind of Polish harshness. If I were British, or not a Catholic, or not so close to death and to the body as we are, I don’t know if I could take those pictures. It’s also kind of Polish to have the coffin on display in the living room. Nobody does that in England, but that’s still practiced in Poland in some places. Not everywhere, of course.

And somehow it’s nice to have the death of my brother out in the world as a fact, not as some kind of dark story that I only talk about when I speak to someone I know well. On one hand, it’s a nice and public way of displaying grief and somewhat helpful to me, but on the other hand it’s also a very discreet way of telling the story of loss. I think the project works really well as a book because it becomes private. An exhibition can run the risk of being a bit too in-your-face, but this work is really intimate and it helps it to be a book. It’s emotional and hard to look at, but it creates nice conversations with people because everyone experiences loss.

Yes, I was curious, since you’re photographing your family, if there was any confusion or resistance about what you’re doing, but it sounds like the opposite.

It was really my dad who said, “Come in and take a picture,” and then I felt alright. I found that taking those pictures was a kind of nice occupation for my mind at the time—in the aftermath, when you can do nothing. The camera became this protective shield from a shocking situation. When someone so young dies, you just don’t know what to say. There’s nothing to say, you know?

Did you set any guidelines or barriers about what you were willing to publish about your family?

Yes; not about my family but about my brother. I didn’t want to show him. I had a few difficult pictures that I could have included but did not. I did not show him dead, he only appears very tiny in a framed family portrait in one of the images at the beginning that set the scene. You see close-ups of him or his blurred hand; you see my dad crying over the coffin but you don’t see the coffin. There are no pictures of him dead or alive because it would make it really sentimental.

So, it wasn’t a moral or emotional guideline but an artistic guideline to avoid sentimentality?

Yes, but also, you have to be able to live with the work. Some images, if they reveal too much, you just don’t fancy living with them. The way I edit my work is that I put it on the wall and look at it, then a week later a few come off, then I get infatuated with one and change my mind. I think it comes down to time. It always needs time.

Much has been said about the relationship between photography and death, how do you see it?

Photography deals with time and in this respect it always deals with death. When I was writing my MA thesis, I looked at a lot of things about death: it’s too explicit, or too ugly, or too obsessed with the corpse, or it’s the media version of death. It’s either death porn or this inability to talk about death. The image of death has been reduced to something completely abstracted and elsewhere; it’s almost not a part of the everyday. People die in hospitals nowadays, people try to prolong their life endlessly—death is a taboo. When someone tells you that a person has died, all you can say is, “my condolences.” It’s almost a formula to respond to death. People don’t really open a conversation up at all.

In Olivier’s essay, he writes about your book: “Here photography isn’t used so much as an act of remembering. It is used as a process of forgetting.” Honestly, I found it a heartbreaking sentiment. How do you see it?

That’s a good one, huh? I wonder. When you make something like a book that exists by itself in the world, it’s almost like remembering, but maybe the process of making it is about forgetting. Or, not forgetting, but moving on.

I could see what he meant, because it opens with the starkness, or the drama of the death, and then slowly there are introduced these signs of life, and things that are more mysterious and colorful and playful. So, it does feel like the return of life.

Yeah. Life carries on. It’s true, it becomes a bit more lighthearted later on with pictures of the boys. At the beginning, it really is kind of hardcore with my mom with a towel, and my dad over the coffin—they’re hard images to look at. That’s the immediate aftermath of the death of my brother and then it does become lighter, I guess. But, when I look at the boys, sometimes I wonder, “Why him?”

Sometimes one feels the emptiness, like in the picture of a computer on the bed but no one there, but then there are these few jokey interiors and the Polish apples and rainbow on the building. I’m glad you think that because I didn’t want it to be all extremely sad. It is somewhat amusing.

I think the amusing side of it is what makes it both relieving, but also all the more bittersweet—the idea that life moves on. It re-normalizes. And, with that, the idea that the city carries on, the other boys carry on, and you’ll be okay, your parents will be okay…

Yes, but, you know what? However much I would try to separate myself from it all, when I think of it and of the trauma, I think the look in my mum’s eyes has changed. I think when you lose a child, you never get over it. I’m a sister who lost a brother, but my parents have lost a child. Apparently one never, ever gets over that.

So, I think that life carries on, and the pain becomes less over time in some way maybe, because you’re more removed and you’re no longer remembering the everyday so clearly, but I think people change. I guess I’ve changed and my parents have changed. And the family dynamics have changed. It’s maybe a longer question. It does become lighter with time, obviously it’s not as heavy as at the beginning, but one misses people. When I go for Christmas to my parents’ home, it’s no longer the same.

There’s the difference too between creating a narrative out of a situation, and the reality itself, which is more complex and involves a lot more different things that might not fit neatly into the narrative.

And formal qualities, it’s true.

What do you think about your brother now? I mean, this book is about your experience, your family, your loss, and so it’s focused on him but it’s not really about him.

Yes, it is about everything else but him, really. It’s kind of about what he could have been, what he could have done, the places he visited but with other people in those places. His presence is kind of retraced from what was left behind, but I surely focus on different aspects of it than he would, because he couldn’t take me through it himself. So, it’s my found story of his life, a kind of Polish life, told with a bit of distance too since I was already living outside of Poland.

My brother was becoming a nice, interesting teenager. When you are 13, something starts to happen: you’re no longer a child, per se. One year, I passed Maks on the pavement, and I noticed that the guys were all dressed up in these uniforms and he was super happy, and I thought, “Oh gosh who is this…” I wanted to photograph him but he was rushing, he was always rushing. I thought I would come back and photograph him, but then I was too late. So, I’ve kind of done what I planned but without him being in the pictures. I spent time with his friends and wanted to know everything about him: where he went, what he did, what his life was like.

I think I miss him, you know? Sometimes, like the other day when the book was done, I just sat down and cried. I don’t usually cry about these things, I just try to carry on, but when the book was done, I just had a moment one evening, where I thought, “Oh my fucking god, now I can finally grieve.” Finally I can say I miss him, and he can become again my dead brother rather than being a project, so it’s a really nice thing to drop off my shoulders.

I miss him. If I’m honest I wish he was around. It would have been cool to have him around because he was a really nice kid. He was a fearless little creature.

Alicja Dobrucka’s photobook I like you, I like you a lot is published by Kehrer Verlag and is available for sale online. Learn more about Alicja Dobrucka on her website.