The female nude: a genre of photography that is heavily tried and ambiguously true. Women photographers have tried to reclaim authorship of the female experience through their work, but is it possible to be naked without being nude?

The Self-Absorption of Creation A Review of Patricia Townsend's book Creative States of Mind

Creation may be the most perfect collaboration of the internal and external: it is where ideation meets materialization. It makes sense then, that to better understand the process of creation, it behooves us to better understand the mind. In her new book, Creative States of Mind: Psychoanalysis and the Artist’s Process, Patricia Townsend approaches the intersection of mind and creativity through the branch of psychology known as psychoanalysis, defined primarily for its focus on the unconscious mind as the actor responsible for our beliefs and behaviors. The controversial elements of psychoanalysis—many in psychology and medicine consider it discredited as a healing science and fundamentally illegitimate—echo through Townsend’s book, and will be read accordingly as either instrumental or poppycock. The psychoanalytic approach, however, is not the book’s main problem in credulity.

Creation may be the most perfect collaboration of the internal and external: it is where ideation meets materialization. It makes sense then, that to better understand the process of creation, it behooves us to better understand the mind. In her new book, Creative States of Mind: Psychoanalysis and the Artist’s Process, Patricia Townsend approaches the intersection of mind and creativity through the branch of psychology known as psychoanalysis, defined primarily for its focus on the unconscious mind as the actor responsible for our beliefs and behaviors. The controversial elements of psychoanalysis—many in psychology and medicine consider it discredited as a healing science and fundamentally illegitimate—echo through Townsend’s book, and will be read accordingly as either instrumental or poppycock. The psychoanalytic approach, however, is not the book’s main problem in credulity.

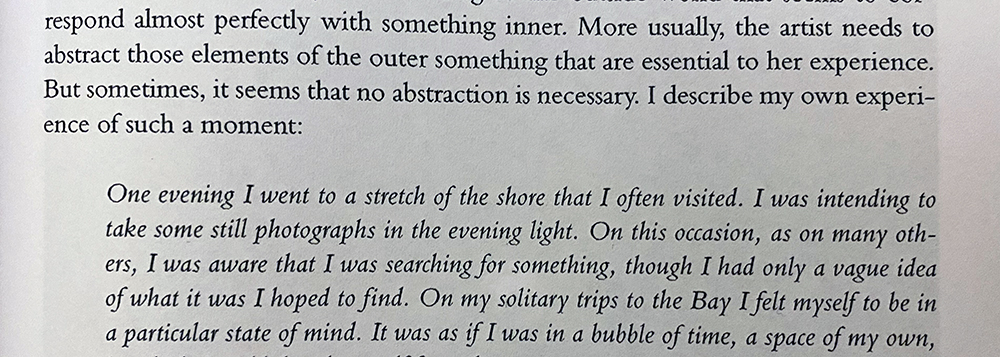

In the book’s foreword, Ken Wright explains that Townsend, as an artist and psychoanalytic psychotherapist, “explores the phenomenology of artistic creation, using her own experience and that of the many professional artists whom she interviewed to take us into the creative experience.” This is mainly accurate: Townsend does take her own position as a psychoanalyst and as an artist to explain the intersection of these fields, and does draw on interviews with other artists to illustrate her view. However, the exploration of this intersection is performed with a pseudo-objective vantage point; on one hand the author reports in academic language on the writings of leading thinkers and on the experiences of those whom she has interviewed, while on the other hand, she frequently defaults to quoting herself and referring to her own art works and processes as proof. The result is therefore not that Townsend’s book takes us “into the creative experience,” as claimed, but rather, into her creative experience.

It is unclear what happened: Is the author victim to her own unconscious, and cannot even see the problem of generating her own evidence to substantiate her case, or is the book just simply, but wholly, misrepresented by suggesting it is an academic representation of artistic creativity? The book would be better positioned as artistic research, whereby an artist gives context to her own practice through exploration of an academic question—a type of work that has its own merits and audience.

This reason I make this distinction is not because it’s important to write a critical review of a book that I might otherwise have tossed aside for pedantic self-absorption. If that were the case, I could’ve written a two-word review saying, “Don’t bother,” and saved myself the next ten hours of writing. Rather, I think it’s worthy to discuss the book’s failings specifically because they serve an important lesson for any creator: the journey of making work can cause one to lose perspective.

In the case of Creative States of Mind, solipsism overwhelms the work. To be fair, the topic itself may have set too tempting a trap: Creation and psychoanalysis are both fields that ask a person to look inside oneself. It would have been prudent to acknowledge this hazard and steer clear of it entirely by speaking only on the works and words of other artists. Unfortunately, instead, the self-absorption is compounded; Townsend merely uses the framework of objective distance to examine herself more closely, losing True North of the work.

This is fascinating too considering that Townsend is indeed writing about the role of the unconscious in creation. She describes artists for whom, “the process of making art involves not only states of which we are aware and which we can describe but also processes outside our awareness about which we can say nothing.” That is, she can readily write about gaps of consciousness in others or in principle without being able to witness or correct for her own. This is human—so very human.

The relationship between the self and the work is one that Townsend discusses at length in her book. Because it’s psychoanalytic at root, one won’t be surprised to find mother/child relationship deconstructions as part of an explanation for the creative process. (She does take this into a rather unexpected direction, ignoring altogether the idea of an artist “birthing” their artworks, and instead describing the artist as a baby essentially re-enacting through the work her desire to mold the mother’s breast. I can’t even.) However, regardless if one agrees with the extremities of Freudianism or the psychoanalytic perspective, there is relevance in considering the process of individual differentiation, and how we as artists relate to our work as distinct from ourselves. Townsend describes two states of mind along a continuum: the artist’s “extended self,” which is the extension of the self-experience to include the work, and the “observer self,” which allows the artist to think and make decisions about the work as something apart. The interchange between these two states, Townsend argues, is what enables the development of the work.

With this in mind, it’s sensible to conclude that artists can spend too much time or invest too much of themselves on the “extended self” end of the spectrum, and integrate their work with their identities. This has obvious hazards. Yet, what’s hidden in plain sight is that both ends of the spectrum still revolve around the self. Thinking about one’s work and thinking about one’s self both involve giving primacy to one’s own world. And it’s here, trapped along this two-dimensional continuum, that a creator can mistake intensely focused navel-gazing for insight into the world. It’s certainly what seems to have happened with this book; the author forgot to look out into the three-dimensional world.

Artistry can involve obsession—but it doesn’t have to. A creator may be involved, as Townsend argues, in a “never-ending attempt to find herself in her work,” but not all creators are. In the wake of a book so wracked with self-examination, it feels imperative to emphasize that not all explorations are inward.

Though we may be fundamentally unable to escape ourselves, a certain wisdom arises when we are able to let go of the thoughts that place us at the center of everything. If—and that is an if—creation necessitates a state of mind that gives primacy to one’s own world, then it is worth finding other occupations, hobbies, or people that challenge and give balance to that mode of being. Typically, working with others like editors and publishers also pulls us back from the edge of total self-absorption, though Creative States of Mind is a clear example of those institutions rather enabling it.

For those creators who dig deep into the self and soul for their work, there is perhaps no greater vulnerability than exposing that work to the outside world, and being denied the shared comprehension and love sought in that exposure. That is the risk. However, aside from anomalous cases like the over-validation given to Instagram models through likes and followers, most of us are not rewarded for fanatic attention to self. When approaching creative work that explores the self as a means to greater understanding, it is all the more urgent to find trustworthy external anchors to keep one’s eyes curiously outward, and avoid free-falling—alone—into the innersphere.

Creative States of Mind: Psychoanalysis and the Artist’s Process by Patricia Townsend is available from publisher Routledge.