In the book, Creative States of Mind: Psychoanalysis and the Artist’s Process, Patricia Townsend approaches the intersection of mind and creativity through psychoanalysis, focusing on the unconscious mind as responsible for our beliefs and behaviors.

An Iconic Photographer’s Third Act A review of Stephen Shore's impressionistic memoir, Modern Instances

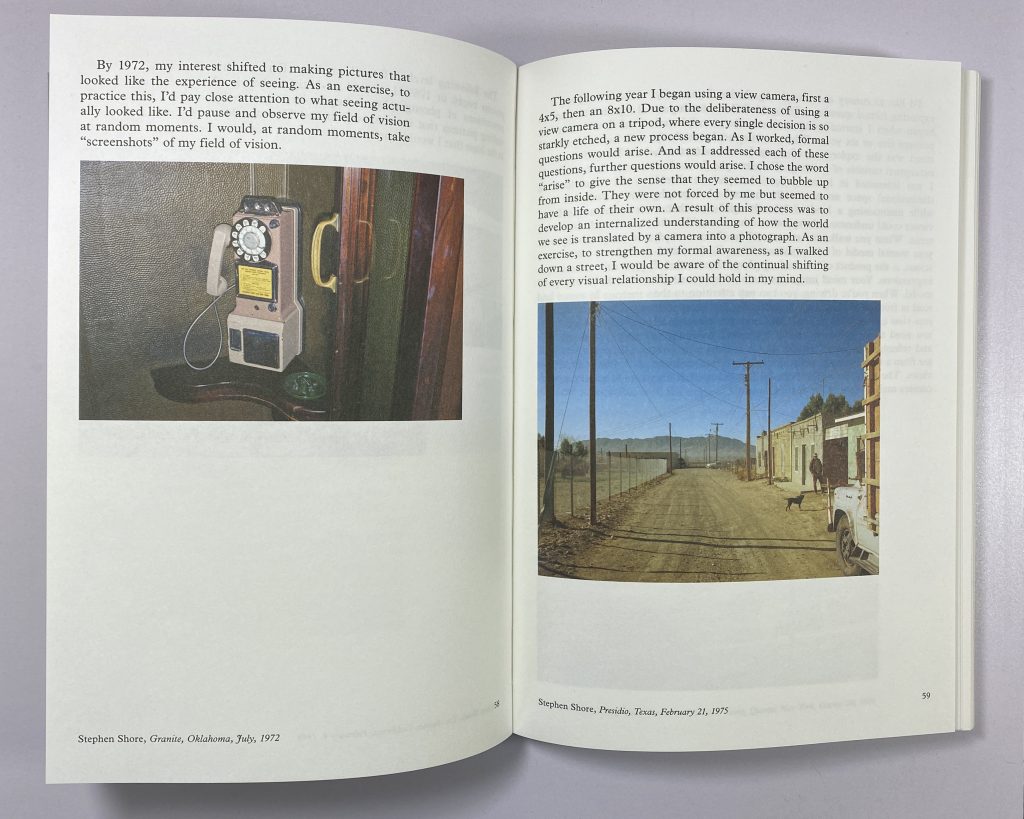

Stephen Shore (b. 1947) has long been an icon of the American photography scene. His early work of profoundly banal scenes created a new approach for an unapologetic “transparency” in photography—capturing a scene with as little pictorial intervention as possible. In his own words, as he told me in an interview with GUP Magazine in 2016: “I wanted to try to just see, ‘What does looking look like? What is the experience of seeing like?’ and use that as a reference for how to put a picture together.” Even beyond his innovative creative practice, Shore has made his mark on photography as an educator, publishing one of the most noteworthy books on photographic fundamentals, The Nature of Photographs, first in 1998 by Johns Hopkins University Press, and later republished in multiple editions and print-runs by Phaidon throughout the 2000s. Now, he has just released a new book, positioned as an “experimental memoir,” Modern Instances: The Craft of Photography (MACK, 2022).

Stephen Shore (b. 1947) has long been an icon of the American photography scene. His early work of profoundly banal scenes created a new approach for an unapologetic “transparency” in photography—capturing a scene with as little pictorial intervention as possible. In his own words, as he told me in an interview with GUP Magazine in 2016: “I wanted to try to just see, ‘What does looking look like? What is the experience of seeing like?’ and use that as a reference for how to put a picture together.” Even beyond his innovative creative practice, Shore has made his mark on photography as an educator, publishing one of the most noteworthy books on photographic fundamentals, The Nature of Photographs, first in 1998 by Johns Hopkins University Press, and later republished in multiple editions and print-runs by Phaidon throughout the 2000s. Now, he has just released a new book, positioned as an “experimental memoir,” Modern Instances: The Craft of Photography (MACK, 2022).

Modern Instances brings together a mix of Shore’s personal anecdotes, reflections, and influences. It is, essentially, a “third act” preservation document, whereby the 73-year-old tries to distill through words and images the path and meaning of his life thus far, both as an act of individual sense-making and collective legacy-creation. Shore himself clarifies in the book’s introduction how he sees the distinction between The Nature of Photographs and the new book: “Where the earlier book was an objective study of a medium and how that medium interfaced with the world, Modern Instances is a subjective scrapbook of thoughts and impressions. An impressionistic memoir.”

These differences are apparent, though there remain some similarities of style. Shore continues to write with a condensed elegance, but allows himself in the new book more room to expound and reflect. He likewise still infuses Modern Instances with lessons, both of life and photography, but here they are told by way of the context that delivered him those insights, rather than the detached, authoritative voice of The Nature of Photographs. For those who are fascinated by Stephen Shore as a person, given his remarkable life as an image maker, educator, and influencer, this can offer an insightful view into the formation of his personal and professional being. His writing effortlessly expresses advanced concepts in photography, like equivalents and structure, as accessible truths.

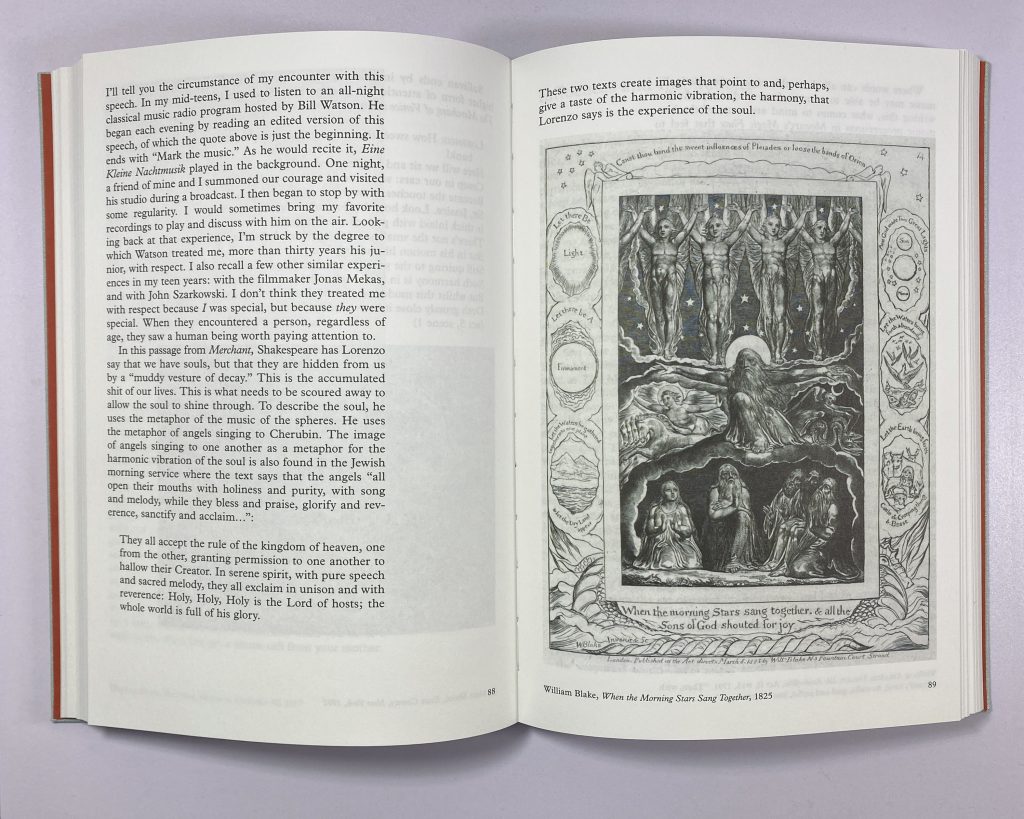

Shore’s influences, as referenced in this impressionistic scrapbook, are many and varied: plays by William Shakespeare, astronomical illustrations of Johannes Kepler, paintings by Claude Monet and Paul Signac, the poet Mahmud Shabistari, maps by the monk-cartographer Fra Mauro, Japanese woodblock prints by Utagawa Toyokuni III, a novella on fishing by Norman Maclean, movies by Orson Welles, photographs from William Eggleston and the talks and writings of other photographers such as Robert Adams, Edward Weston, and Lee Friedlander…. And so on.

What’s noticeably absent, however, is women.

This was already somewhat an issue in The Nature of Photographs. Apart from the several photographs by Shore himself, and those marked anonymous, The Nature of Photographs includes only 13 photographs by women, or around 17%, give or take. This absence irked me, but the book was made in the ‘90s, before many of the conversations about representation really took root among the mainstream of photographic thought. I can make enough intellectual excuses to still admire the book.

Alas, with Modern Instances, the chasm deepens irreparably. Beyond the inclusion of a paltry two images made by women (well, three, if you want to be generous and include work by the husband and wife duo Bernd and Hilla Becher), Shore also fails to mention hardly any women, apart from his wife, among his countless references, despite the many fields and media in which he otherwise demonstrates such an engaged interest.

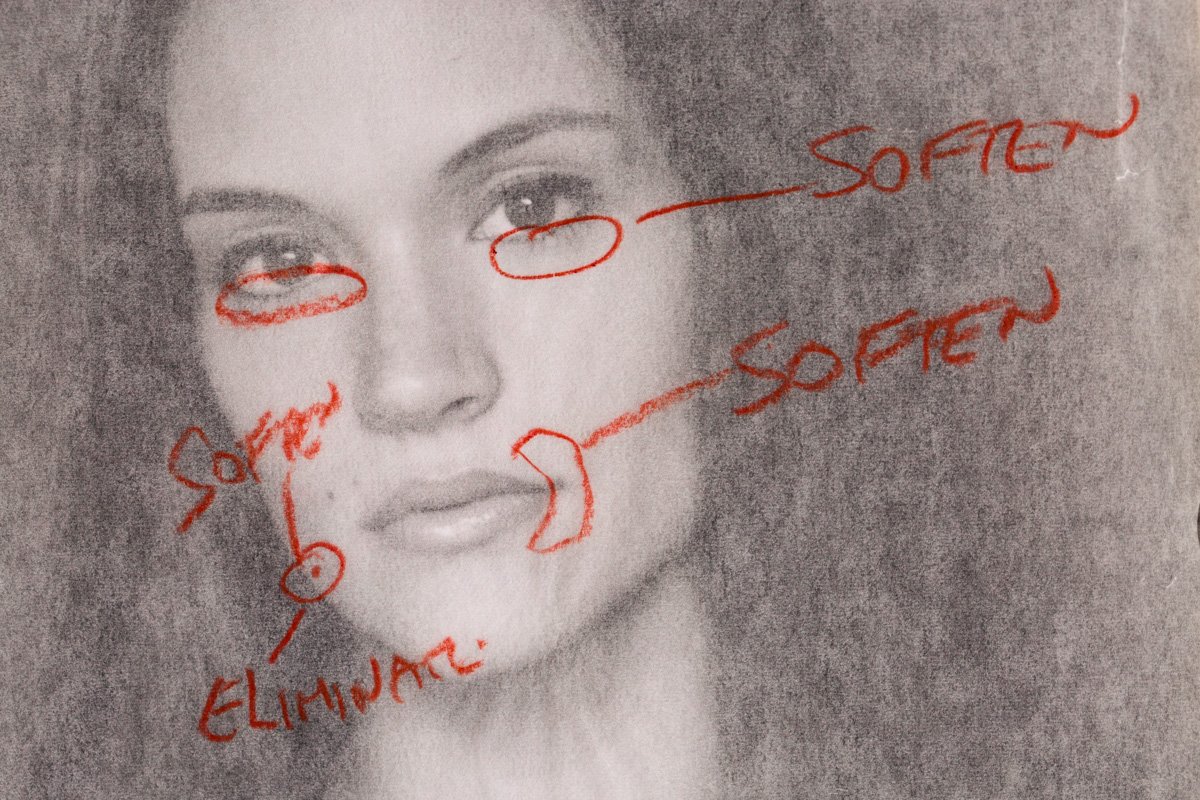

This disparity is upsetting in the context of Shore’s book, in particular, for two reasons. First, because Shore’s philosophy emphasizes attention and looking. There is even a chapter of the book called “Attention”, which he begins: “One of the repeated themes in my work is the idea of experiencing the everyday world with attention.” His appreciation for the cultivated art of attention is unambiguous. How does someone who makes a point of giving careful attention overlook such a glaring omission? There are two possibilities: he overlooked it as an unconscious blindspot, or, worse, he did not overlook it—he chose it. The problem of this omission is amplified by a transcribed conversation with George Miles included in the book, whereby Shore explains how he, over time, worked through the “mastery” of his discipline, through three levels, the physical, depictive, and mental. As a reader, I’m left dumbfounded, and a little heartbroken. Is this the culmination of one’s “mastery” of photography?

The second reason is more personal. By Shore’s own words, The Nature of Photographs is more objective than Modern Instances, which is intended to be subjective. It is, after all, Shore’s story and reality that he wants to share. This subjectivity becomes all the more unflattering, however—it illustrates that when he wants to be objective, he can include a few women. When he wants to be himself, however, there are few women worth thinking about or writing about. It’s this realization that fills me with an uncomfortable truth: This book is not for me. It’s for the comfortable default of men.

As a long-time admirer of Shore’s work, this is a tough pill to swallow. I consider him influential in my own path as a photographer and writer of photography. It causes me to wonder, darkly, what other messages I’ve absorbed unconsciously from his work over the years. Reviewing this book, I’m tossed back and forth between values: it is as meaningful as it is irrelevant.

Modern Instances: The Craft of Photography is available from publisher MACK.