In her most recent photobook, Let Me Fall Again, photographer and bookmaker Julia Borissova presents a part-factual, part-imagined construction of the life of Charles Leroux, a professional jumper.

True Labor: An Interview with Lupita Carrasco

American painter Lupita Carrasco offers a poignant perspective into a world not often seen from the first person: the life of a caregiver. As a mother of seven children, aged four to nearly thirty, and caregiver to a mentally ill parent, Carrasco’s life has been shaped by her tending to others. With such phenomenal responsibilities, it’s remarkable for a person to have also forged a life as an artist, explaining why it’s perhaps unsurprising that her creative viewpoint is so exceptional. And yet, for precisely that reason, her work hums with profundity.

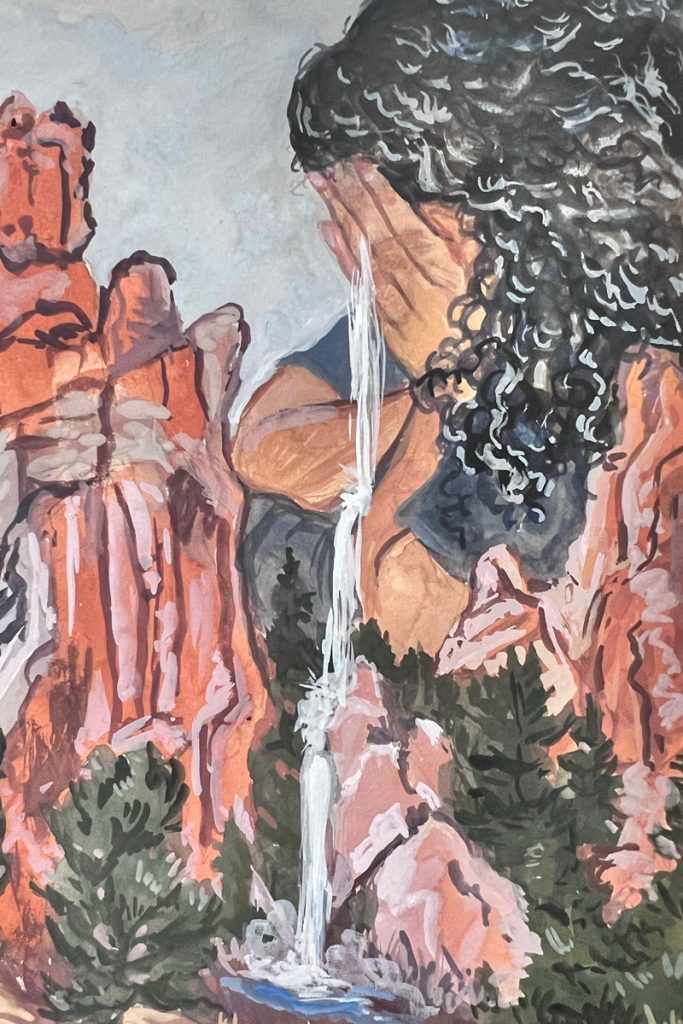

In her painted series “Motherhood Is Forever”, she portrays a lifetime of mothering through small moments and poetic metaphors, lighthearted daydreams and deep wounds. She invokes symbolism to draw out layered meanings and conceptualize motherhood as a lived experience. We see in Carrasco’s visual language the indigenous Mexican and African American ancestry she holds dear, yet her message wields universal truths. Altogether, the vastness of her topics and scenes combine to form an epic understanding of the maternal. In this interview, Carrasco speaks about bearing witness to the awe-filled moments of the home, how being a mother and caregiver affects her art practice, and the intertwined experience of being both a mother and child.

It can be so patronizing to ask women “How do you balance a family and a career?” when men are never asked that question, but given your circumstances, I do feel like that’s where we have to start. It’s truly remarkable to look at this prolific body of work of yours, and consider it despite all your caregiving responsibilities. How do you get it done?

I ask myself every day where I can get more time to paint. There’s really no time. I am constantly complaining about the dishes, the laundry, the sweeping, the dog, the kids’ homework that is for some reason always last minute. It’s always chaos and I’m not good at routine. Today I had a minor meltdown because I was going to take a shower, and I didn’t get to take it so I just threw on a dress. I was freaking out about our call together because I couldn’t find the email anymore, and wasn’t sure I had even sent a response. I don’t know what happened. I totally dropped the ball again. So, that’s my life: I am always dropping the ball and picking it up and dropping the ball and picking it up. An endless series of messing everything up.

But here’s the thing: you still get the work done. Your individual paintings convey emotion and metaphor, and beyond that, they all build towards this profound, all-encompassing concept. That’s getting it done.

I am really driven to make work. When I’m not making the actual paintings, I have a lot of sketchbooks that I carry with me in my purse, so whenever I have time, I go out for a walk and I take a few moments to try and capture the landscape. And when I don’t have time, I’ll work from a photograph. It comes and goes, too: I’ll try to do that almost daily, and then I’ll go through periods of time where I can’t get anything done for like a month or a couple months, where I don’t touch any kind of art-making, and then I’ll just get into it again.

The main thing is to make sure that I always have a studio accessible. Like right now, I’m at my studio table in my bedroom, and I have all these art supplies here. I have a studio downstairs in the living room, and I have a studio in the backyard for ceramics, and then my purse is also a studio because I always keep some supplies there.

You work also in a few different media, can you elaborate on that?

I paint with gouache and oils, and I also do ceramic works. Recently I had a show called “Magnificent Wild” together with another artist, Audrey Gray, and we both showed works on childhood. I did ceramic pieces that were dedicated to the inner child. They were like little shrines or altars to the inner child. This had coincided with me putting my mom into a nursing home, and one of my kids having an emotional crisis, so I was feeling all these different experiences of having children and being someone’s child myself that married together so well. I think that even though my work is evolving and changing, it does all circle back to motherhood, childhood, that intertwining experience of the two and how they affect one another. I think about my own childhood and how it affects the way that I raise my children and interact with them.

You’ve been a caregiver to your mother for more than 20 years, due to her mental illness?

Almost 22 years, yeah. She’s in a nursing home now for the last few months, but I’ll still do overnights because she refuses showers there, so I have to bring her home to get her to take a shower. She won’t change clothes there, she won’t wear pajamas. I’m still the one cutting her nails and brushing her hair, and all the while I’m trying to heal from the trauma of our relationship.

Sure, she’ll shower in our home environment now, but when she lived with us she refused showers. She used to refuse to take her meds and I got so much blame and shame for that as her caregiver, but now the nursing home has stopped all her meds because she refuses them, and that’s just seen differently. It’s so strange to me. Two weeks ago I had a conversation with the people at the nursing home, and they told me they weren’t able to check her sugars a couple times a day like I asked because she just gets too angry. And this was my experience with her for the past nearly 22 years, but—apparently—it’s okay that the nursing home makes that call and not me. She’s in the nursing home because that’s where everybody told me she would get the best care, which is to say, better care than I could do. But they’re not better. A light bulb went on in my head. I just thought: “I absolve myself.” I spent that day absolving myself of the shame, guilt, and all the horrible feelings put on me by the health community, by my family, and by all the judgy people. And that doesn’t mean that all those feelings are gone, it means that I have to keep absolving myself over and over from the weight of that shame and guilt.

Nowadays, we frequently hear of the shame and guilt around motherhood, but I think it’s rarer to hear that about other forms of caregiving.

It’s just because we’re women. If I were a man, I really don’t think that people would say things like, “You don’t take good enough care of your mom,” you know? They’d be like, “You’re doing so awesome! Yay! Gold star!”

What do you see as the differences, if any, between caregiving and mothering?

That’s hard to answer, because I sometimes feel like I haven’t really experienced my life because it’s been so wrapped up in other people’s needs on both ends.

I think it’s this: Mothering feels like giving all of yourself to teach someone to go out into the world with all the love and knowledge you can share, so that they can carry on without you. Caregiving for a parent is also giving all of yourself, but knowing that’s not going to go anywhere. It’s just going to keep declining and she’s going to keep needing more of me.

Now, since I got my mother out of the house, I know that I have a choice of whether or not I will keep giving all of myself. I’ve gotten that to a point where I am routinely honoring my needs and myself, and I’m learning to do that in motherhood as well. I have to consciously remind myself: Hey, you’re a person too, not just a machine to continuously do for other people.

How do you bring these ideas into the works? What does it feel like to make them?

When I make the works, there is this desire to not only have the moment seen, but also to have a space where other people can connect with something that they also experience but maybe they don’t see in the world around them. So, I’m extending myself and my experiences into an image, for other people to be able to identify with something that maybe they don’t get to see as artwork.

A lot of the expression in my work comes from the isolation of motherhood. I feel that mothers are kind of locked up in these little worlds where we do so many things and we may see a lot of people but we don’t get to have frequent interactions with peers. I know there’s other women that are really good at doing that, like getting together for playdates and doing self-care, but I’m not one of those. I don’t know that experience. My experience is this locked away, isolated realm, and I see all this heartbreak and all this beauty and a real span of human emotion—and I’m the one that’s witnessing it. So, I’m bearing witness and I have a real desire to give those moments the same type of importance as a presidential portrait or a great war battle.

Do feel differently about your works when you’re doing them than when they’re finished?

When I’m working in a sketchbook, it’s almost like a dialogue that’s happening. I’m problem-solving, I’m digging. I’m excavating my soul a little bit and I’m getting the imagery out. Often, I’ll get words out too, and I’ll write some things or make notes of symbolism that’s related. I also pull out my phone to take pictures that capture certain feelings, and I store those into certain albums for future paintings.

Then, as I’m crafting the painting, that’s when things get distilled. I try to consider whether there’s anything I can eliminate, or add, or how I can really amplify the voice of the message in the image. So, the actual painting is another form of problem-solving.

And then, once the pieces are up on the wall, I can see them all interacting with one another. That’s important because the way they interact in a gallery is very different than the way that they interact in my living room all over the floor and on the mantel and just piled up behind places. Then there is another level of meaning that comes out when that artwork interacts with the public. Sometimes, if I’m lucky, I get to hear people talking about how they relate with what they’re seeing. When I give an artist’s talk, then there are questions that arise, and that deepens it even more.

So, at the very beginning, it might just be this little whim of an idea that crosses your path and you decide to pull this one whim out of all these other things going by. I’m going to single this one thing out and do something with it. Then, by the time that you’ve crossed that threshold all the way at the end, and are giving an artist talk and receiving questions from an audience, that work has itself grown and aged, as a person would, with its own experiences and its own meaning that is now larger than when you first conceived it.

How do you go about transforming your emotions into images? What’s that process like for you?

That’s really easy actually. It’s so automatic, it’s rare that I have to go searching for that to happen. For example, I have a little gouache piece that has these eyes in the sky that are kind of crying snow. The moment when that happened, I was walking with a friend and we looked up and suddenly the snow was coming right down on our faces. It wasn’t like we saw it in the distance coming, it was just a cloudy day and suddenly there was snow in our faces. We had been talking about some painful things, and in that moment, I remember that I thought of eyes crying the snow. So, the imagery was just there. I might be out in nature and suddenly will imagine an elderly person curled up in the branches, for example, and I’ll see that in my head and link it to the cyclical nature of our lives, or I’ll see a cactus and see myself naked in that cactus, surrounded by it, because of all the struggles in my life that have pricked me from every direction. So, all that imagery just happens naturally as I’m moving through the landscape. The images just well up in me. It’s not something that involves effort. The effort comes when I’m making the piece.

Since you exhibit your works for sale in galleries, how do you approach the commercial aspect of your work?

I consider the economy that I’m in. I live in Colorado Springs, so I think about the people who live in this economy. As an artist, you can price your work however you like, but I’m concerned with whether or not those pieces are going to make it into people’s homes. I do consider people’s ability to own something that they love. I consider sizes and what I can store in my space. And then I also consider what I see as beautiful and the things that really make me want to keep looking at something. That’s what I think about when I’m creating images.

Sometimes people want to know how long an artwork takes, and I don’t spend a lot of time on paintings. Sometimes it only takes an hour. Why? Because I’m fast. Because I’m in a hurry. I know how to paint fast because I’m in a hurry all the time. My whole life is in a rush.

How has it been a challenge to combine making your art with being both a mother and a caregiver? Have there been sacrifices you’ve made along the way?

What I have sacrificed is self-care, but more than anything, that comes from caregiving for my mom and not so much for my children. If I imagine taking the component of my mom out of the picture 20-some-odd years ago, and just think about what it would’ve looked like if I were just raising my children and making art… that would look very different. I wouldn’t have to worry about my mom stealing my art supplies. I wouldn’t have to worry about her judgment. She’s very judgmental about what I’m painting, so it’s hard to say where I’d be had I not lived for so long with my mom in my space. She’d come in and say, “Why’d you cut off the top of her head? You can’t do that,” or put little sticky notes over a penis to censor it. So, self-care is something that has suffered but now I’m learning to weave that in to my art-making.

Honestly, I just think that the reason people say you can’t be both a mother and an artist has to do with the fact that a lot of people view the art that mothers make as not “real art”—as not really having value. And I think that is related to mother’s work being seen as not having value. It’s how society views motherhood, women, and women’s work as something that “just happens”. It doesn’t really require effort, it doesn’t hurt your feet and your back and your hands and make you sweat. It’s true labor, as is growing a human being in your body and then giving birth to them. True labor.

You can’t tell me that that the things that I’m doing in this home don’t have value, but somebody sitting in an office sending emails or making ads for products does.

What do you wish people knew about motherhood?

A friend of mine who has an autistic child told me a story. She was talking to the therapist that works with her son about how everybody tells her that she’s doing this or that thing wrong. And this therapist told her: “I did all these things to set my kid up to be successful, to get out there in the world with things lined up and have a great life… and now she’s angry at me because I pushed too hard. I did this too much, I did that too much.”

So now, we joke all the time: You’re doing it wrong. If you’re a mother, you’re doing it wrong. It’s our little joke, when we’re having a miserable day and complaining to each other on the phone, washing dishes or whatever. “Well, just remember, you’re doing it wrong!”

How do you think motherhood changes over time?

Oh, it changes so much. I remember two things on either end of this.

I remember being in labor for the first time and being in the hospital room eating chili fries. The doctor came in and took the chili fries away and said I couldn’t have them until after I gave birth. That moment, when the chili fries were taken away from me, was when I realized I was going to have a baby. I was a 17-year-old kid with no siblings, who didn’t grow up around kids or babies, and so I was totally naïve about that entrance into motherhood, and had to go from not really caring about anything at all, being really reckless and destructive with my life, to being so focused on this person that depended on me entirely. Understanding that I had to do everything in my power to keep this little person safe. The reciprocal love that came from this child was my entry point into unconditional love. He didn’t judge me, he didn’t look at me in a way that I was flawed, or I needed to do something to receive his love. That was where I learned unconditional love: from my first child.

Then, fast forward to just recently, I was telling all my children, “You all are not going to get the same parenting.” The kids that were older got a totally different mom than the kids in the middle and the kids that are at the end because I’ve had a lifetime of learning and trying things out that don’t work. All these experiences have brought me to the mother that I am today, who is so different than the mother who was 17, and the mother who was 24, and the mother who was 28 and so on until 47 and here I am. You know, I’m still figuring it out.

Learn more about Lupita Carrasco and her work on her website.