"When you give yourself over to the inactive state, you’re also giving yourself over to an internal roaming. Without that, there really isn’t a capacity for surprise, for discovery, for actually learning something new about yourself or the world."—Josh Cohen, in our interview about his new book Not Working.

The Beautiful Body: An Interview with Jamie Schofield Riva

Photographic artist Jamie Schofield Riva is a former model and actress—someone who earned a living from society’s ideas and idealizations of beauty. Yet, it was something she says she was “always conflicted” about. From a young age, she saw how people reacted to her physically, and how this gave her a certain kind of power but also a higher degree of scrutiny and expectations. After having children, she became even more aware of the experience of having a female body and what lessons she might be unwittingly passing on, particularly to her daughter.

In her new photobook Girlhood: Lost and Found (Daylight Books, 2023), Schofield Riva takes to task her lifetime relationship to beauty and fashion, examining how her personal experience inhabiting a body often clashed with the messages conveyed using her image. She combines documentary images of herself and her daughter with lost objects on the street, and weaves in archival images from her childhood and personal journals. The amalgamation of materials results in a nearly frenetic search for an elusive “self” amidst the constructions of femininity. In this interview, we speak about the power of privileged beauty and the lived experience within a body that underlies it all.

How did you decide this was a book that needed to be made?

It wasn’t a choice, I just started to notice something was happening. I started to see these lost objects on the street and there were all these feelings and thoughts coming out when I saw them. I realized the themes that were being reflected back to me. It was forcing me to look at things that I had been internally battling my whole life.

Even as a young girl, it was very obvious to me that this – my body and the way people viewed my body – was going to be part of my experience as a human on this planet. And even though I’m talking about this issue from inside of that experience, I can kind of always rise above and see the bigger picture as well. So, yes, fitting a certain ideal of beauty is my identity and experience and I’m a part of the world that sees things from a certain perspective, but I can also see the context around it. I mean, these lost objects on the street, in one reading they’re symbolic of throwing away and losing aspects to yourself, but beyond that, I find so much beauty in these broken things on the ground. Here are these weathered, decaying objects, and it’s such a similar process to what happens to our bodies. Our bodies age and crack, and there’s beauty in that, too. There’s beauty in what time does to things, and I want to see my own body in that way. I want to see the changing lines on my face and all the emerging marks on my body be able to find beauty in that.

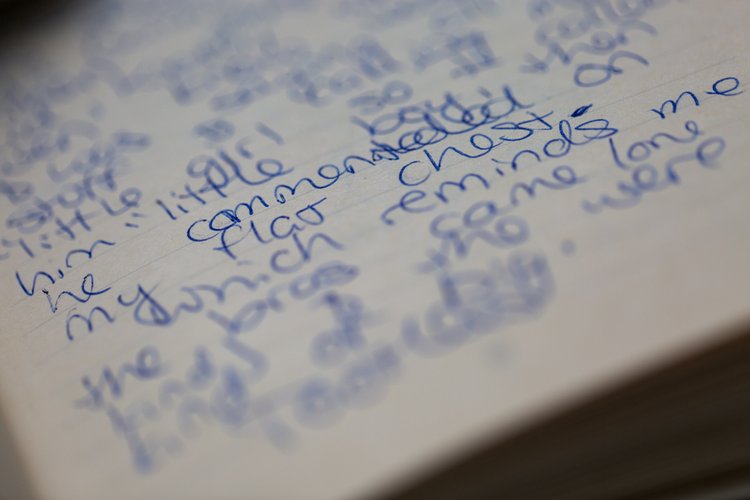

I found these old journals of mine from when I was a kid, some of which are published in the book, and I can’t believe the things that this 11-year-old could see. I was already keenly aware of and had feelings about and maybe even felt trapped by those experiences.

Can you give an example?

For example, there’s a poem that I wrote about a woman whose heart was broken, but she wouldn’t cry because she didn’t want to ruin her makeup. I wrote this little note under it – in a very dramatic 11-year-old fashion, very “cringey” as my kids called it – that she wouldn’t do what was true to herself because of how she would look to someone else. I can’t believe that’s what I was thinking about when I was 11, I wasn’t even wearing mascara yet, you know? But then, that came full circle when I found a Kleenex that I had saved when I was in my mid-twenties from when I was crying and didn’t want to mess up my makeup. When I pulled the Kleenex away, I saw this perfect design, so I decided to save it. I wasn’t thinking about the poem then, I didn’t even remember it, but when I started to pull materials together, those two things really connected.

There were other journals from that time about a boy commenting on my flat chest or a poem I wrote about needing to do your hair the right way or wear the right clothes. Now, I look back and wonder if that’s when I started to feel like my body was not just my own. That it was going to be subject to all kinds of critiques and judgments about whether it was “good enough” for someone else.

You write that this book is a “personal journey to discover a way back to the person I was before I learned how the world saw me.” When do you think that was?

Even earlier than those journals, I think. We start learning at such a young age. Even as a little girl, I often felt things that made me incredibly uncomfortable. My mother used to ask me why I was so uncomfortable around men, why I didn’t want to hug them. I’m not saying they were already sexualizing me, but I was sensitive to the fact that there was something there. You feel how people respond to you and what they respond to. You learn what’s valued by them and certain treatment you might get. You might naturally play into that. Because there’s power in it too, right? I remember very clearly in high school, when I was old enough to be waking up to my own sexuality, there was a point where it switched in me and I realized, “Oh, there’s great power in this.” But you can also be trapped by it, so there’s two sides to it.

When you’re so little and innocent, you can’t help but feel how the world reacts to you, which could be in a positive or a negative way. That’s going to affect you. It can be creepy and scary, but also empowering, and I had to grow into an understanding how to navigate things.

That’s true for everyone. We just slowly start feeling how the world gets their hands on us. We come into this world as a true spirit with just a big, open, loving heart and it just slowly gets chiseled away at. You kind of conform, you kind of change. You mold yourself based on how people react to you and you don’t even consciously realize that you’re doing it.

How do you think the experience of being a girl or a woman is peculiar to this?

Well, I can only speak to being a girl because that’s my experience. I have a son and I really try to drop into the world of being a boy because they have their own struggles and I want to be clear that everyone has their struggles, but girlhood is what I can speak to because it’s my experience.

Women aren’t really allowed to age. We’re expected to look a particular way. We’re expected to maintain looking a particular way while we’re also maintaining every other aspect of life. It’s unreasonable. There is a lot of unrealistic pressure that we’re constantly trying to live up to and it just feels impossible. I personally would like freedom from that, and I personally would love to shift that for myself and for other women and to create space to change the idea of what’s beautiful.

Let’s be clear, too, it’s nice to feel beautiful. I think all of us should be able to feel that way. I still want to feel beautiful, but I want it to be on my terms. I don’t want someone else to tell me “You’re not supposed to have wrinkles,” or “You’re supposed to be a particular weight.” I want for my feeling of being beautiful to come from my idea of beauty. So, I suppose that’s part of what started my exploration: Where did I – where did all of us – learn what beauty was in the first place?

Let’s talk about your career as a model. What did that look like in reality?

I was always conflicted – always conflicted – about doing that job. Maybe that also held me back professionally, because I was constantly fighting myself while I was doing it. Like, I love fashion, I love the idea of it as a creative means of expression, but on the other hand, don’t tell me what to wear.

Even from a young age, I loved fashion and photography, and so I started to do some modeling in my hometown—just small gigs at the local mall. At first I thought, “This is so cool, I definitely want to do this.” But then I had some medical issues that stopped that in its tracks. I thought it was over because my body wasn’t right for it and never would be. So I moved to New York City and studied photography, which was really my first love. Agencies would still try to recruit me for modeling, but I’d say, “No, no, I’m a photographer.” I remember thinking, “I’m an artist now and I need to speak out about real issues. How could I even be a part of this beauty industry that’s shallow and superficial? That’s not who I want to be.” But, really, inside, I knew I had all these medical issues and felt like I’d never measure up. So it was a conflict that I’d bounce back and forth between.

When I finally did model, I felt like I’d sold out to this big machine that’s not good for the world and not healthy for people and sending the wrong messages to people. I was super conflicted, feeling like a part of the machine that I wanted to speak out against. But eventually I got to a point of acceptance. I do think that people should own what they have and use it to empower themselves. So, if you’re born with a math mind, go be an accountant and use what you were given, profit from it. And someone said that to me when I was really struggling: “Use what you’ve got. You’ve got to pay your rent. There’s nothing wrong with that.”

Once I flipped that switch in my head and I was positive about it and I felt in control of it versus not, then I felt it was empowering. And someone else said to me, “Here you are complaining about this, but there’s a million other people who wish they could be modeling.” And it was a turning point because I realized if I’m negative about it, it’s just going to keep being a negative experience.

So, to answer your question in a really roundabout way, I was always conflicted about modeling. I don’t think there’s one right answer for it. The closest I came to resolution was when I got to a place where I decided: I was given this body. I was given this face. If I can support myself that way and I can pay my rent while I’m pursuing something that I care about, which is acting or photography, and take care of myself and have a roof over my head, then I’m going to do that and there’s nothing wrong with it. And then there were other times where I felt horrible about it. I felt like I’m a fraud, I’m not being my authentic self, I’m meant to do a lot more.

What does that authentic self look like?

I feel much more at home behind the camera. I’m much more fulfilled and happy talking about the things that we’re talking about and sending these types of messages out into the world versus being the girl in the magazine.

I remember being a young girl, and I’m at home sitting at my parents’ table looking through some catalogs – like the Victoria’s Secret catalogs or whatever they were – and looking at those women in their underwear and their bathing suits and then looking at myself and thinking, “Why do I have that roll falling over?” I remember doing that, really picking my own body apart and comparing myself to these women. I remember understanding that this is what the woman’s body was supposed to look like. And if I’m not that, then I’m not good enough. I remember that feeling.

And so, now, when I look back at those pictures of me as the model in a fitness ad in a magazine, I ask myself, “Is there a girl out there who looked at me and didn’t feel good enough because she didn’t look like me?” That feels terrible. I’d much rather be the woman I am now, who shows her gray hair and her stretch marks and says, “Hey, I’m human. I’m in a body and I feel bad about myself sometimes, too.” I’d rather be a real human woman than the girl in the magazine.

Can we talk about the medical issues you experienced and how that affected you?

Starting from when I was 12 and into my early teenage years – the most formative years of our bodies’ physical development – I was in a back brace for severe scoliosis. To give you a mental picture, this wasn’t just some little knee or wrist brace you might be picturing but more like a bulky, full-body cast. It was physically and mentally painful. There were a lot of hospital visits, I had to wear clothes to disguise it, I didn’t want to be touched. I know deeply what it means to be the opposite of the traditional standard of beauty. More than that, I felt betrayed by my body. I thought that I would never be normal, nevermind beautiful. I had to hide my body for years, I was ashamed, and when I looked in the mirror I saw a deformed monster.

I explain all this because it’s important to understand that, yes, I did model but I know the other side as well. I couldn’t fit the perfect mold of society, as my body was forced into a different kind of actual mold for four years. Even after that, it’s not like everything was magically “fixed,” I was living in a body with physical evidence of scoliosis and I lost work because of it. The scrutiny of the beauty industry made this experience really tough to bear. I am very familiar with how it feels to not fit traditional beauty standards, even though I meet many of them and was part of the industry that helps to define and sell those standards, in part because that industry made me fully aware of every way that I didn’t measure up.

They may sell an image of perfection but that tells you nothing about what it feels like to be in that body.

The overwhelming sense I get from your book is one of searching. After all this exploration, what do you know (and not know) about being a girl?

I love that you got that from the book, because you’re right that this work is about the searching. I think like while we’re alive on this Earth, that’s what we’re here to do. We should never stop searching and looking at ourselves. And self-awareness is so important because we’re always changing.

My daughter said to me, “Well, what are you trying to say to the women who do Botox, aren’t you going to offend them?” But that’s not what this is about. There’s no one way for everyone to live, and I’m not judging other people for the choices they make. I want for us to be able to talk about it and feel comfortable in our insecurities, and about what empowers us versus what we feel like we “have to” do and what might be causing us pain and making us miserable.

To answer your question a little more clearly, what I know is that we are under pressure – unrealistic pressure – and it’s damaging and it’s hard. I don’t think it matters how strong you are or how confident you are; If you’re a woman in this world, you feel that pressure from some somewhere, whether you work in front of a camera or not.

That much I know. The rest of it… you know, I’m in it. Some days I feel great, some days I don’t. I still dye my hair. I’m not ready to go full gray, but one day I will be. I think making this work has allowed me to own my choices and show the struggle. I don’t think there’s a place free of all that, but you can work towards it. At least, I’m trying to.

Since humans are social creatures, do you think there’s ever a resolution to that conundrum? I mean, short of being a full sociopath and disregarding what people think, it seems that we’re really hard-wired to care what others think of us.

Right. I think a lot of it comes down to individual personality. I’m definitely a perfectionist in many aspects of my life, and will be hard on myself and judge myself, and some people just aren’t that way. But, like you said, you can’t be a person in the world and not be affected by external messaging, whether it’s subliminal or blatant. Yes, you can be really strong and aware, but if you don’t stay on top of it and keep reconnecting to who you really are and who you really want to be, you’re going to start falling into it.

I think we have to be really careful about what we surround ourselves with: what we look at and listen to, and what we bring into our energy field that makes us feel that we have to be a particular way or that there are a particular set of standards. Being aware is helpful, but there’s nobody immune to it. We’re all consumers of our environments—me too. And, speaking for myself, I can put work out that I hope will shift that, but I’m definitely not saying that I’m above any of it. I’m just here to talk about it and heal it in myself and hopefully others. That’s what I really care about and what I find meaningful.

However, I keep thinking of the privileged position at stake in this conversation, like when a wealthy person says that money doesn’t really matter. So, let’s talk about what that position really has meant to you and your life.

I have gotten reactions to this work like, “How do you have the right to talk about beauty (or aging, or weight) when you still look a particular way?” And I get that. I respect that and I’m very sensitive to that. I think about it a lot.

What I want to say about the experience that I’ve had as a person on this planet is that when you start making a living off of how you look, you’re scrutinized more. My body and face, I mean. I could tell you all kinds of things about my body and face that the average person would never see, because I’ve been under a microscope. You’re in front of a camera and literally have people telling you what has to be fixed, and then trying to fix it or cover it up, or editing various things out of photos that you didn’t even know were flaws. It’s just a part of being in that industry, to be under attack in a different way than a person who’s just out there walking the world. Although, I do think any woman walking the world is also under attack in the sense that she’s never enough.

Also, I think when your beauty is something that you have used as a tool in your life, and you start to lose it in the aging process, it’s also a different experience than if it had never been a major part of your life. And I just have to stop for a second to say how uncomfortable this conversation is for me. I don’t want to talk about “how beautiful I am.” I would never think that way or talk that way about myself, but I have to for the sake of this conversation about the work. It makes me want to vomit to talk about “my beauty” or to say something like “I’m so beautiful.” I don’t walk around thinking that about myself or talking about myself that way, but this is my experience.

You asked me at the beginning about why I made this work. Well, part of it is also that I need to accept that I’m losing my “beauty” – as far as what the world thinks is beautiful, not what I think is actual beauty. There is this “thing” that I’ve had my whole life, that I was given and was able to use as a tool and make money off of, and it probably created opportunities for me. I mean, you still have to be yourself because there are plenty of physically beautiful people who are awful to be around, but it gave me an open door, an opening. And if I don’t have that anymore, who am I then? Who am I and what am I going to do?

I knew that if I didn’t go in and figure it out, and figure out how to age, how to feel powerful and beautiful in my soul when I’m 80, I’m going to be fucking depressed. I’m going to start fighting it with knives and needles, injecting things into my body and sucking things out. I don’t want to do that to myself. I want to love myself. I want to feel good.

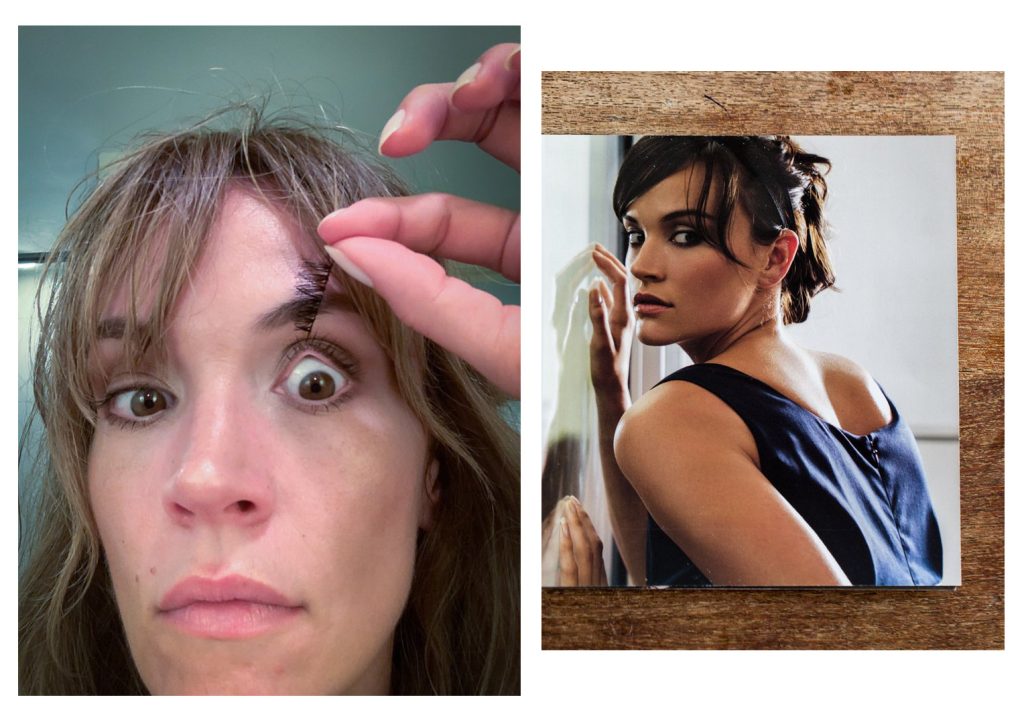

There’s a magazine insert to your book that includes some of your old modeling work, though it’s photographed kind of askew, as though something is distinctly wrong or misleading. How do you feel looking at those pictures of yourself now?

There’s a magazine insert to your book that includes some of your old modeling work, though it’s photographed kind of askew, as though something is distinctly wrong or misleading. How do you feel looking at those pictures of yourself now?

I juxtapose those modeling pictures with my old journals from the same time very deliberately. There I am—smiling and shiny and perfect—but then I’m writing about obsessing over one little pound of weight. I’m torturing my body, I’m hurting myself.

I wanted to really show that whatever you think you’re seeing when you’re looking at these shiny perfect things, it’s not real. For me, it was magazines, and now it’s Instagram and social media with the filters, and everyone is curating their perfect lives and looking beautiful. It’s not real, and even though we all say we know that, somehow it doesn’t sink in. I’ve spoken to so many people in my own life who never know I felt the things I did or thought the things I did. They believed the images.

I would like to share the truth that I still suffered. I still felt the judgement and judged myself. I still never felt good enough or perfect enough. So, don’t look at someone and assume something about their lives. We’re all struggling.

This was just my path and I want to shed light on it. I hope that this will make people feel better. Maybe you see that girl in a magazine and wish you looked like her, but she’s got problems, too. Maybe that girl didn’t eat for four days and doesn’t enjoy her life and she doesn’t get to just go home and curl up on the couch and just be comfy and eat and enjoy life and have pleasure. There is a lot of suffering in the pursuit of beauty. People cause pain to themselves—literally hurt themselves—to fit into some made up idea of beauty that doesn’t even exist. The people in those pictures don’t exist, it’s a setup.

You write that having a daughter is part of what motivated this work, as you had to consider what messages you want to pass onward. Have you fallen into the classic parental trap of “Do as I say and not as I do?” How did having children affect you?

That was really the driving force. Aside from just trying to reckon with my own life and experiences, I’ve always felt a struggle with having a daughter, you know? I just want to spare her or protect her from some of these things. It definitely matters what I say, and even more what I do—you’re right. In the Introduction of my book, I write about one moment, where one day she looked at me and asked, “Why do you need mascara to go to the grocery store?” And I just thought, “Oh my God, you’re right.” I’m talking to her about her ‘natural beauty’ every single day, but then she sees me put on mascara to go to the store. That shifted something to me. I decided to show her that I can go out without makeup more often, because it matters what we say but it matters even more what we do.

So, having a daughter shifted everything—everything. Even just being fortunate enough to get pregnant and to carry and deliver my child, that changed so much for me about my body and how I felt about my body. I decided, from that moment on, I’m never going to let my daughter hear me talk bad about my body, ever. It doesn’t matter what I’m thinking about myself that day, I’m not going to say those things out loud.

So, having a daughter shifted everything—everything. Even just being fortunate enough to get pregnant and to carry and deliver my child, that changed so much for me about my body and how I felt about my body. I decided, from that moment on, I’m never going to let my daughter hear me talk bad about my body, ever. It doesn’t matter what I’m thinking about myself that day, I’m not going to say those things out loud.

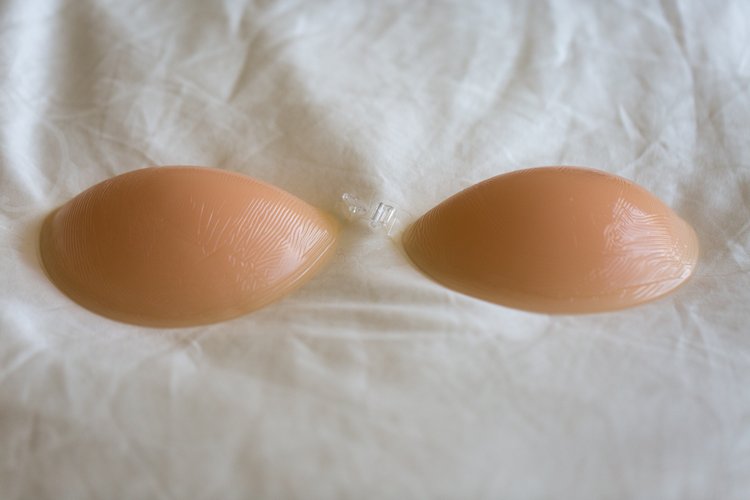

Being able to give birth and carry a child – the fact that I created life with my body, twice – that strength is incredible to me. I just felt that my body should be worshipped. For example, I don’t ever want to feel bad about my breasts again. Like, there’s nothing there, and there’s plenty of options to “fix that” or whatever, but you know what? These things kept two humans alive for two years. They don’t deserve that petty judgment. They kept life alive. They’re majestic.

Becoming a mom did that for my thinking, and anytime I’m feeling down on myself or want to judge my body, I always go back to that.

Being a model is in a sense about drawing people’s gaze toward yourself. Now as a photographer, what do you think it’s important to direct people’s gaze toward?

This work is about shifting that idea of beauty and what defines it for us. I’m very passionate about playing with the definition of beauty, and that’s why I love some of the photos in the work of beauty rituals, these things that we’re supposed to do to make us fit in to the traditional idea of beauty. I like to show it in a way that shows how crazy it is, and how we look so disturbed or crazy while doing them. We make ourselves crazy for it. And I like pointing the gaze on non-traditional subjects of beauty, like portraying myself with a made-up face and hair armpits. I’m passionate about challenging the ideals and I think if we could have more of that in the world, then there would be less pressure to fit one ideal of beauty. Then all of us could feel less pressure, and we can just have fun and feel sexy and beautiful on our own terms.

Girlhood: Lost and Found is available from publisher Daylight Books. See more from Jamie Schofield Riva on her website.

Girlhood: Lost and Found is available from publisher Daylight Books. See more from Jamie Schofield Riva on her website.