"Even as a young girl, it was very obvious to me that my body - and the way people viewed my body - was going to be part of my experience as a human on this planet. "—Jamie Schofield Riva, in our interview on the power and scrutiny of beauty.

The Profane and the Divine: An Interview with Pierre Liebaert

Belgian photographer Pierre Liebaert dives deep into the thin boundaries between the real and the unreal, the abstract and the visceral, and the profane and the divine. In his latest series, “I Believe in the Nights,” named after a Rilke poem, Liebaert presents a look at the metaphors of ritual. The photographs, a selection of which were exhibited at this year’s Unseen Amsterdam photography fair by Archiraar Gallery, are taken at ritual celebrations like Carnival in many cities, but the images are strangely detached from their specifics. Liebaert separates himself from the descriptive to evoke an animalistic reaction to the raw encounter of the human symbolic act. In this interview, we discuss how he has changed as an artist and person since our last interview, the meaning behind rituals, and how metaphor can bring you back to yourself.

Your latest series, which is still in progress, is about ritual. Can you tell us about it?

In my native city in Belgium, they perform an annual ritual, which is a reenactment of the fight between St. George and the dragon from the 15th century. It’s a mad, mad moment, where people have to catch the holy hair of the dragon. It’s set in the center of the city, in a kind of arena that’s separated with yellow sand like gold. The people can approach this zone, but never enter it. It’s a big fight and I was very shocked by it—although I don’t like the word “madness” in this case, because I see this event as very necessary. It comes from your innards. The people don’t really know why they are here, but they have to be here, and I love the moment when you’re not thinking about what you want to do, you are just compelled.

Maybe the heart of my question is: What does the ritual fill in you? What does it represent, this invisible part of you? For me, rituals bring us in touch with the realization that life is chaos, but they also establish and prolong something invisible—and something disappears.

What disappears?

Time is flowing. Everything is flowing, and inevitably disappearing. You can’t catch life. You can’t catch the people you love. A ritual takes place for you to accept that things disappear. This is the most difficult and painful thing for us to accept, because it’s very hard to understand that, actually, nothing really disappears, it just moves from one form to another. Everything changes and sometimes you just want to stop this flow—to stop everything.

It sounds like you’re describing the concept of detachment.

Of course.

So, is the point of the ritual to let go of your attachments? Or to spend time in attachment?

So, is the point of the ritual to let go of your attachments? Or to spend time in attachment?

It’s very paradoxical. Ritual is always the link between two polarities: between the highest and lowest, the profane and the divine.

You know, we humans are a kind of mistake. The ritual is maybe the reconciliation, the place where humans come to the right place. Rituals are always about myth, which is derived from the Greek prefix mu (μύ), which means to keep silence. But, in my view, we are mistakes. It’s very clear that we shouldn’t be here. There’s a kind of humor there – humanity is a big and beautiful project, but we failed. I’m sorry, but we failed.

In what way are we mistakes? Do you mean a biological mistake, a divine mistake?

It’s absurd that we are here and we have no reason to be here. We are weak, we are poor, we are without defenses. We just survive every day. Nature is much stronger and breaks everything. We have only our minds to resist. Maybe it’s best to abandon yourself, to just let go. To submit.

I love this word, to submit, because it means that you put yourself into something else. You accept that you’re within something that embraces you. And for me this means there is a movement. During these rituals, or Carnival, you’re always moving—smashing the floor, making noises, or in a procession or dance. It’s to keep your community in movement. Maybe the most beautiful thing about Carnival is to reintroduce you to cosmic movements, to reactivate something. Maybe God is movement, if we have to name something. For me, this word is unpronounceable, but it’s movement. You know, this thing happens, and when it happens, it provokes movement, energy and materials. Something becomes visible.

The way you talk about movement makes me feel like we are not a mistake, we are part of it all.

Yes, of course, and yet, we are also outsiders because we have a consciousness. We know that we have just a short period here, and this knowledge provokes a kind of lie. You can embrace the condition but you can also create diversions for yourself. There is the divine part of yourself, the part which is luminous or transcendent, but you can choose to ignore that and explore the poorest, most vulgar parts as a diversion. That’s why, for me, we are a part of it all but also outside. We are sinners.

In Greek, sin is hamartia, which refers to the fact that you lost your center. You are there with your bow and arrow, trying to aim, but a sinner is somebody who lost the center. I love this image of us: we always want to be in the center, to make good decisions, to be in the right place… but we are always outsiders, losing our aim.

Where were the photos taken?

I began with the rituals of my native city. It was the first time I thought I was seeing a kind of illusion: there is a procession with bones inside of gold boxes, and for a young person, it’s very strange to see gold on something so brutal and static – bones. For people who grew up with it, it’s normal, but if you take another perspective, like looking down from a hot air balloon, it’s something very touching and strange. I felt something when I encountered it.

I also went to Switzerland, Spain, Holland, Germany, and Italy. I’m not trying to have an encyclopedic look at rituals, but to say something about how we are linked by something more than our biology, but also spiritually. These two parts of us are intertwined, our biology and our spirit, like sisters. The rituals just take a different form, because people have different realities. Mountains, sea, flat country, agriculture, shepherds—these are different realities, and rituals have different gestures because of that.

It’s important to say here that your pictures are not descriptive. They don’t try to describe these rituals in a documentary way, but rather, they speak in metaphors.

I tried to erase the anecdotal. This gives space to think about the darkness, to get closer to the root of the rituals, why they speak to us, and what they say about us or the material of this reality. For me, there is no darkness, we are just blind. You know, St. George never really killed the dragon—he just put light inside. It’s like Perseus and Medusa. He didn’t kill her and St. George never killed the dragon. They just embraced a part of themselves and filled the dark with light. Medusa was beheaded, but it’s a metaphor to illustrate that what you are doing is irreversible. There is no way back. When you do something very important, you change deeply and it’s impossible to go back. Every cell in your body is changed. This is why you have to be prepared.

You said to me in our last interview that death is the great motivator of our lives; everything we do is because of death. What does it say about these rituals that involve the threat of death or the metaphor of death, but nobody actually dies?

Death is a transition. Life refuses to die. It’s a mystery, but life wants to live. It’s like an acorn holding the potential of the tree inside. It gives me a kind of vertigo to look at an acorn, knowing that a tree will emerge from it, but also that the seed must die to begin something else. Ritual puts you at these very thin moments, between one thing and another. We can learn a lot from death, whether we keep our silence or play a role with a mask. Death has a message for us and, through these rituals, it can speak through us, if we let it.

We are traveling in this vehicle—our bodies—like a train. For something to happen, it has to be carnal, visible. They need the materiality to exist, things have to be somewhere.

Since materiality is so important for us, what can the immateriality of a ritual give us?

To show us that the most important thing is not here in front of us. It’s in between. Maybe the most important thing that a ritual does is to solidify and to reactivate the links between contrasting ideas to understand that everything is linked to something else. And yes, for me, the most important word is religion, which came from religare in Latin, or religere—it’s two words. Religare means “to link.” In French it’s relier, it’s to put two things together with a thin line. This is very beautiful, because religare means that we link with others but you also link with yourself. So, it also means to reunify yourself. You take all your fragments, all your attempts every day, all of your life—and you put it together.

You can be one with all you are seeing and all you are feeling, and with all the deaths of your life. We die every day. Every day parts of you decay and the things around you, too. Through a ritual, you can reunify what you have been, what you are, and what you are becoming.

The other word, religere, means to re-read. Like when you open a book and read it again. In French, lire is to read and relire is read again. When I read a book as a 20-year-old, it’s not the same when I’m 30. For me, this is why art exists. It’s to have something fixed and you pass through. Art is fixed, life is moving, and we are passing through. So, texts have to be read, read again, again and again. It gives you the possibility to read yourself again and again.

When we talked about your last project, you said that you thought it broke you, or that something was now broken because of it. So, as we speak now about transitions, how is the current project affecting you?

At the beginning of this project, in 2016-17, I began to go to the monasteries in Belgium. The monks there share my love of words, stories, questions, and doubts. It seems to me that this stance of curiosity, humble and ample, is essential in a monk’s life. The monastery is a kind of laboratory of yourself and of the world: It’s a place where you can observe and everything comes to you. When I started going, I would stay far away from the rituals. I sat at the back of the room and was very discreet, because I was a little bit lost there. I felt bad because I saw the church as a big authority figure. I didn’t grow up in a Catholic family and never had much contact with Catholic culture, but I was very curious as well. I know that religion can hurt very deeply because it lives in a very, very intimate part of ourselves. I can really understand how religion hurts people and compresses them.

I was staying in Rochefort Abbey, and I was in the sanctuary together with the worshippers, behaving like a very proud person. I just wanted to show that I don’t believe, you know? I was on the bench, but without the paper to follow the ceremony, so I was alone and could stand somehow apart from things. One day, a person behind me just whispered, “Psst!” and handed me the paper. I froze up and took the paper and I began very shyly to sing—to participate. And I felt something. Four or five years ago, this would have been impossible for me, it was all too foreign. I was too proud to get on my knees. I was very controlling.

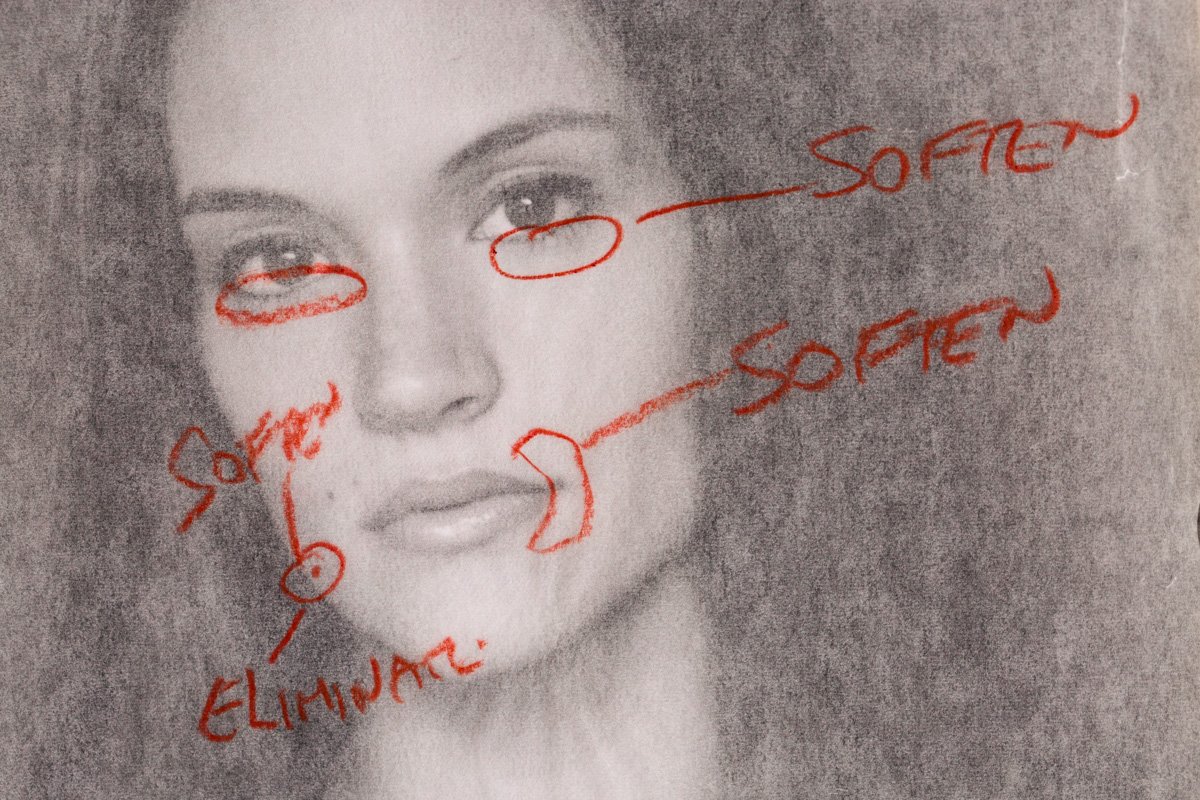

In my last project, I was closed, totally closed, while the person in front of me was totally nude. It was a very strange, unbalanced relationship. I was playing a big role but it was very important for me at that moment, so I don’t judge myself for this. Now with some distance I can look at it. Before I was too close to it, too close to the strange feelings I had.

So, now you can experience it more? Not just watch and stay in control, but participate and maybe lose control?

Yes. Maybe what I want to say is that now I try to say “yes” to everything. “Yes” to what happened. It’s like “amen,” you know? I have to say yes, because there’s no other choice. We have no other choice.

Well, you were able to say “no” before this point…

Maybe it’s the story of the acorn again. To begin something is just to be in movement. When you reach the highest point you begin to fall—it’s what the “climax” suggests. There’s a kind of acceleration or momentum to this fall.

The depression is a very important part of ourselves. We must accept everything: accept sadness, accept mysteries, accept darkness, accept the moment in which you lose everything. Maybe for me, to love is to accept that the person or the objects of your love are distant from you. That’s one of the symbols of Easter, you know? The person you love will leave you and never come back. You have to love this big distance between you and another person, between you and what you see. You don’t love the person, you love this distance between the two of you.

Love is distance? This sounds like the opposite of intimacy to me.

In this distance, you preserve the place of the other. You accept that the person has his own world, his own imagination, his own place. The image that comes to mind for me is the intersection space of a Venn diagram—mandorle, in French. The almond. For me, it’s the mystery of relationships. It’s the intersection where we connect.

At Carnival and in other rituals, people come together. Everybody comes and they walk in the same direction, but everybody has something intimately private going on, too. It’s very moving to see the unity of people celebrating—even celebrating each other’s apartness, even among the many different profoundly personal reasons they each have to be there.

You’re looking at the ways in which these various rituals are similar to one another, like themes of death and rebirth, but in what ways are they different? What other themes are there?

I don’t want to be precise about the rituals—it’s not a definition and, as I said before, it’s not my goal to be encyclopedic. It’s a place where I can find something to build, like a sculpture. I choose what’s interesting for me, and so I move far away from the “postcards” of Carnival, and into the aspects of rituals that engage the full body: rituals with pork bladders, blood, outburst of violence, frights, shit-covered pigs, and where the people eat and drink a lot. There is a certain expression of excess and drama. This is where humanity is playing at something with himself, with the idea of society, with the idea of civilization. What happens when we break all the rules and produce something chaotic? I love to give myself over to this. For a short while, humanity inhabits an irrational zone, where it is pleasurable to play with the limits of shame. To go beyond those limits.

One of the big links between all the Carnivals that I chose is the sacrifice of innocence. It’s maybe one of the big themes in humanity in general: to put all the responsibility of sin into one person and kill him, or kill something that can absorb all the heaviness of humanity. But, also, it’s to preserve something very precious. I think it may be also to accept that something separates you that is untouchable.

The Universe is always expanding, but so are we. Something is developing all the time and at Carnival, where we celebrate expansion, there is the dirty side of things but there is also the silence. In the small extract of the project that I’m showing here at the Unseen fair—it’s just six pictures—it’s about the border or the limit between our civilized and animalistic parts. You can see how closely our skin resembles pig’s skin – little hairs on pink skin. On a cellular level, pigs are very, very similar to us. We could have a transplanted pig’s heart. They’re emotional and it’s very troubling. I’m also showing the limit between day and night – there is a picture where you see six guides in strange clothes climbing a little hill. They appear just in the back of the picture and it’s as though they’re asking us to follow them toward this thin line between the night and day.

Maybe the ritual is the space where these two parts – the inside and the outside – can embrace each other, and that’s why it’s so emotional. That’s why it’s so hard to talk about rituals. Usually, when you ask people why they’re there, celebrating the ritual, they don’t know. They’ll say something like, “I don’t know, because my parents did it every year…” but it’s not a good enough reason for me. It’s just skin-deep. This part of us is inaccessible. A ritual is not with words, it’s with bodies, hearts and presence. It’s the place to find silence, even in the noise, because we can’t find the words anymore. Then we’re able to hear.

Rituals are also a place where the inside and outside are reversed. It’s a tension or perturbation. During Carnival, all the doors are open, and you rebuild the community from strangers. Everything outside goes inside, and everything inside goes outside – like tongues and teeth, innards like pork bladders, blood, everything overflows like a geyser. You provoke something, and it’s all too much. It’s unmanageable.

Does a ritual need to be so extreme?

This is precisely why the rituals are very short, because it’s impossible to maintain this state. It’s very brief, it’s very ephemeral. In my native city, it’s five days, from morning to very early morning. Afterwards, you return back to something very clear. It’s very strange and you cannot share your experiences—it’s too indescribable and unbelievable. It’s like waking up and trying to describe a dream. You put together fragments of events, and maybe you find some lingering marks or signs that serve as proof that something happened.

In our last interview, you described the importance of sculpting your own life, and said you were afraid that one day you may be too tired for this work. Too tired to keep fighting the dragon like St. George. I want to ask if you’re still afraid, or if you feel tired?

I’m not afraid, no, and I’m not tired. Creation means also to be patient. You have to change your position, your point of view. You can’t always be on the inside of something, it’s important to get some distance and just observe that some things happen without you.

I learned that it’s possible to be silent, and something happens in the emptiness.

Rituals taught me that some things happen regardless of me. We are all in something that, well, it doesn’t exactly protect you but it has no intentions against you. Because you are in this stuff, even when you are doing nothing, something happens. And sometimes an arena arrives, and you have to go fight the dragon because, of course, you want to reactivate desire.

How will you know when the project is finished?

When I feel that there are some recurrences. When I go to a Carnival in Switzerland, or in the south of France, I begin to feel that there are echoes. I don’t know the city because I haven’t been there before, and I don’t know the gestures particular to this ritual, but at the root, I see something similar. I can recognize something in the feeling of the picture that I believe I’ve already communicated. At least, then I know that maybe it’s time to change my position, or to introduce something new.

It’s paradoxical, because to reconnect with life, you have to create something very far away from life and this tension provokes something very close. The masks of Carnival have this goal: the artifice of the mask forces a distance between you and what you’re seeing, but it also forces you to become closer to yourself. With the mask, you wear it on the outside of your body to turn inwards. It’s the same with photography: you position yourself very far away from the subject but still feel very close, and this provokes something in you. You have to be far away from yourself to get closer to yourself. You become a stranger to get closer.

Art is very close but also very far away from the things that are captured. To me, art exists to shine a light on something and to be with forgotten things. A lost reality. I love the idea that artists are there to invite lost realities and lost people and lost feelings.

What lost reality currently occupies you?

The infamous, the ugly, the wicked, the grave, the vulgar, the religious.

For me, there is no darkness. There is just the absence of light. There is no cold, there is just an absence of warmth. And there is no wild dragon. A dragon is just the part of you that you reject. Rituals let you offer your hand to what you reject. Art, too, gives you the possibility to extend your hand.

When a picture catches you very intensely, it forces you to be silent and to be patient. You let the picture into the deepest part of your eyes and your brain and your body. The picture has to install itself in you to produce something, to change you. It’s why, for me, it’s very important to take time to look at things that are alive but also to look at some things that are still and fixed. Art is like a friend, you know? It’s a friend who shines a light on your rejected parts. Your dark side is very important. It’s where something can be installed that will maybe move something in you. It’s the essence of art: to move something new.

Earlier, you said God is movement. Art is movement, too?

Exactly.

See more from Pierre Liebaert on his website, or through Archiraar Gallery.