"There are definitely days when I don’t have the energy, and today is a day I’m struggling. [...] It really is fighting every day and the project gives me something to fight for in a productive way that’s bigger than myself, which seems to be good for me."—Tara Wray, in our interview about the Too Tired Project.

Kissing Madness: An Interview with Photographer Pierre Liebaert

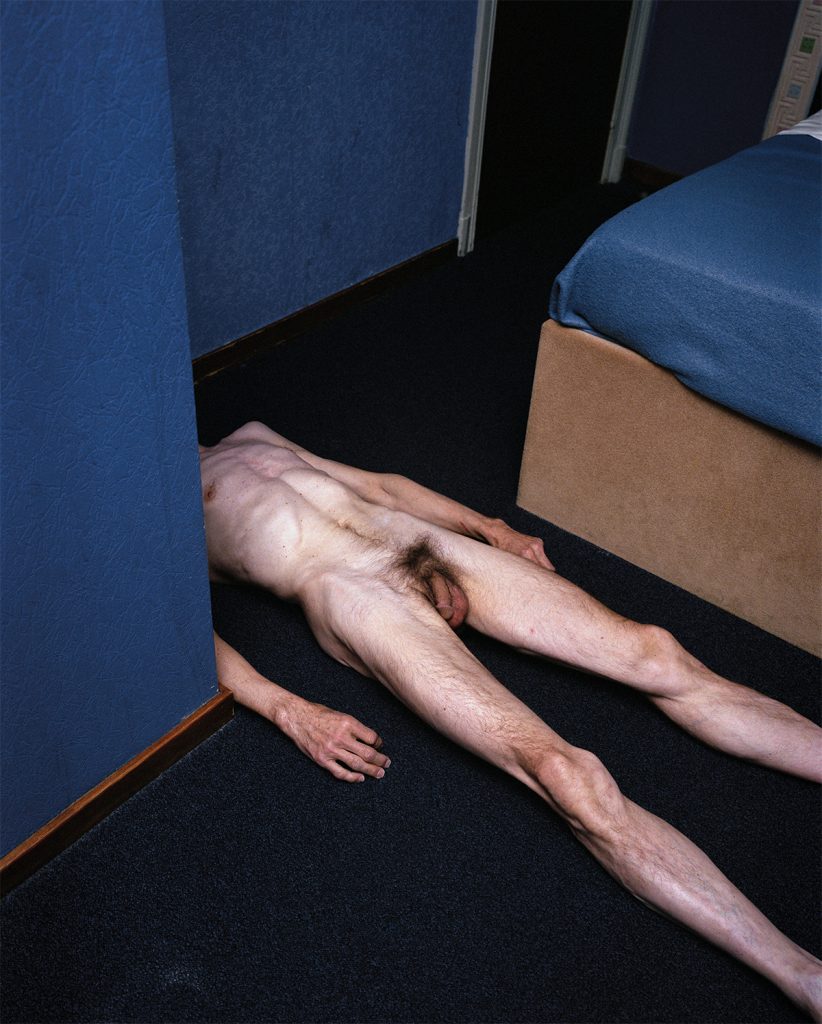

A small room, a closed door … and all the fantasies of the mind unleashed. For his project Free Now, Belgian photographer Pierre Liebaert (1990) placed an ad seeking people willing to participate in a nude photography shoot. Though he was only 23 at the time, and all the respondents were men, mostly in their 40s and 50s, Liebaert met them alone in a hotel room, rented by the hour. While no expectations were set in advance, a certain theatre unfolded between photographer and participant as the men played with the experience, using the freedom of an anonymous encounter to release themselves from the shackles of society. In this interview, Liebaert speaks with us about conjuring the devil for a photograph, the dangerous allure of a secret and the difficulty of being human.

A small room, a closed door … and all the fantasies of the mind unleashed. For his project Free Now, Belgian photographer Pierre Liebaert (1990) placed an ad seeking people willing to participate in a nude photography shoot. Though he was only 23 at the time, and all the respondents were men, mostly in their 40s and 50s, Liebaert met them alone in a hotel room, rented by the hour. While no expectations were set in advance, a certain theatre unfolded between photographer and participant as the men played with the experience, using the freedom of an anonymous encounter to release themselves from the shackles of society. In this interview, Liebaert speaks with us about conjuring the devil for a photograph, the dangerous allure of a secret and the difficulty of being human.

Tell me about the men that you photographed for Free Now. How did you meet them?

It started with photographing people in the woods, for my previous body of work, Big Shit, together with the Belgian photographer Clément Huylenbroeck. On the highways in Germany, Belgium and France, there are some wooded areas next to the highways, and men go there to meet each other. They’re very crude encounters. The men are travelling from their work to their families, and they meet in the woods. It’s not a ‘real’ place – the woods are an idealised place, a place for fantasies. In some stories and mythologies, the woods represent an unknown place, the path to the unconscious.

I met some of the men who go there and spoke with them, and I asked myself: how can a person live with two lives? How can he live with two personas in one person? Or, not only two personas, but three, four, five… This question is the genesis of my work.

It’s not very comfortable to photograph in the woods, though. It’s full of tension, because there’s prostitution and pimps, and this brings hooligans and policemen. Some of the men I met are very ashamed of this kind of life, and the camera augments this shame. It’s a kind of mirror. So, instead, I decided to put an announcement online to organise some nude sessions. I received hundreds and hundreds of answers – from only men.

Only men responded? What did the ad say?

The announcement didn’t specify men, it was just a general call for people willing to pose nude. It was only later, after these sessions, I realised all the people, all the men, corresponded to one type: they wanted the chance to look at their social life from the outside, like taking a hot air balloon ride and looking down from above. And, these men wanted to discover through the photography a second life, their ideal life.

What is this experience like when you’re in the room together? Because you’re not in the woods, you’re in a very small, confined space.

I organise these shoots in a sex hotel, which can be rented for just one or two hours. You finish, they clean up and voilà, there’s a new bed – it’s totally pragmatic. It’s an awful hotel, like a jungle with plastic plants and a baroque sofa.

You meet the woman at the front desk – room 12, second floor – and you go there, lock the door, close the curtains, put on some coloured neon lights… it’s a horrible place, but it participates in the ritual. It’s too much, it’s too different. It offers the models a different state of life. And that’s important because we’re often meeting during their lunch break, between 10 in the morning and noon, or between noon and 1 PM. It’s very efficient: we speak, we take some pictures, sometimes five rolls of film or fewer, then, “Okay, I have to go!”

Living a double life can be considered to be living an un-truth, or living a lie. To what extent do you think this side of them is true – this other side that you experience in the room together?

The truth is situated where you want to see it. (Liebaert laughs at himself, and whispers, “That’s horrible!”)

Maybe, it’s like Carnival: once a year, for three days, you have the authorisation to behave in an inverse way. You have the chance to experience life with the ‘devil’ in yourself. Because you have a mask and you can do anything. Strangely, the photography augments reality, and the truth of the experience. In these sessions, through the photography, they can consider this ‘devil’ part of themselves. These men want to be transgressive, even if it’s only for two hours. It’s a kind of decompression, a purification.

Because, look, freedom is very difficult. It’s very difficult to be free. For society, a free person is not good because a free person has doubts, a free person has questions – very important questions – and these very important questions necessitate time, and after this questioning, he will act. It’s simple to ask a question, but the question drives you to do something, to take some action with your life and to choose. It’s too dangerous for society to have a person who has anxiety, or to have a person who is really free.

It’s like Marquis de Sade, the French philosopher from the 18th century. For society, de Sade is considered a monster, because he chose to live differently, he chose his life. He spent thirty years in prison, because he thought for himself. In his closed cell, he was able to explore his mind, his fantasies and his dark fantasies, to open the walls, escape and discover himself.

Maybe the person in the room with me, masked and nude, is exploring his dark fantasies and he wants to be free – for just two hours! – because society is very oppressive. Maybe in these rooms, it’s a kind of Garden of Eden, it’s a pure place in Brussels.

Is it possible to see it as ‘pure’ when you’re interacting with the ‘devil’ of the person?

Society and the body are very connected. The body has some impurities, like urine, that we have to eject, and society, too. It’s like death in winter and rebirth in spring, it’s a cycle. And in this transition, you create a representation of the devil and kill it. Or, not kill, but control.

Because we don’t kill the night, we don’t kill the noise, we don’t kill the black. It’s a kind of balance. We don’t have to kill the devil, we have to control it, and to play with it. Because otherwise, it will control us.

So, then what is your role in this?

It’s like a priest! (laughs) No, I’m the person who must capture it. I’m the one who generates this session, and then I poke the devil. I play with him, too. But, ‘the devil’ is a very romantic definition. It’s maybe not the right word, because for many people the devil is negative. But, for me, it’s positive – it’s part of us! Like death. Some people try to keep death separate – no! Death is not separate, it’s among us, it’s in life. We have to understand this, because with this concept we can be happier. More peaceful.

Many people are not able to find comfort in the thought of death, though.

But it’s not healthy to refuse to consider death, because all we are, and all we do, is connected with death – all of it. Absolutely all. We consider our life, because death. Time, because death. Art, because death. Love, because death. Children, because death.

It’s too important. It’s our last, our very last experience. It’s a very unique and personal experience. It’s the last experience, and maybe the most important.

What role do the masks play in the process?

The mask participates in this manifestation of the devil, too, in a kind of magical way. Masks are a part of ritual. It’s not a mask to be unknown, it’s a mask to be deep, to find something deep in ourselves. With a mask, we are not human, we are something other than human. We are something higher.

In this case, does it enable the man to become more himself or less himself?

Maybe they discover something different, something powerful. We are very far removed from our animality, we are very human. Maybe too human! We are too much of a thinking being. It takes energy to be human, to be civilised. It’s very difficult to live in a city with five million people, for example. It’s complicated to live with shitty neighbours that make a lot of noise – Ugh! It’s very, very difficult to be quiet, to be calm, to be respectful of another person. It’s difficult to consider the way of life for the other person, to consider their way of thinking and their opinions. It’s very, very difficult.

Isn’t this the essence of being human though?

Yes! And it’s very difficult to be human! We are so far removed from our animality. In nature there are no rules, there is no ‘bad’, no ‘good’. These are human notions, human concepts. Good and evil, god and devil – they’re human concepts! It’s not a natural concept. It’s a concept created by humans to consider and accept their condition. It’s very easy to give our lives over to the hands of a big person. It’s easy and comfortable. It’s easier for human beings to not have questions and doubts, and give them instead to gods…

So, then, do you think what’s happening in the room is animalistic or humanistic?

It’s together, intertwined.

It’s a new notion for me to talk about in this interview, but maybe, it’s about madness. For me, it’s important to experience madness and to control it. Artists have to be mad. For me, it’s essential, but it’s very complicated. We have to control ourselves, to hold ourselves together in our skin, we have to maintain ourselves in rules. And, to be mad or to be an animal, is to be instinctive. It’s very difficult. Maybe to participate in these photo shoots, these sessions, is to kiss the madness. To kiss the animality.

It’s strange because I didn’t think of these concepts at all before I took the pictures, only afterward. When I considered all the pictures and recordings together, it was so impressive to me because it was all the same story, all the same human story, the same need.

And after the session, everyone returns to his normal life.

Yes, it’s like a dream or a nightmare. It’s like a fantasy, it’s not life. It exists outside.

But, they choose to be there with you. It’s something you do together.

I’m very lucky, because in fact, I realised afterward it’s very dangerous. It’s uncomfortable to be in a closed room, and you have in front of you a naked person. But I’m there for the photography, and I have a uniform and a persona. I assume a role, like in theatre.

What is the persona you play?

I take the role of a person in uniform. It’s a kind of domination. You know, it’s a kind of ‘straight’ person, very righteous and very static. I play with it and I love it. It’s very egoistic, but for sure I want to play a game that I’m not able to play in my normal life. I want to be somebody else. I am the photographer: I am very sure, I take charge, command them, and then afterward, I disappear. It’s similar to the models, but also different, because I always say the models are very courageous. It’s more dangerous for them: there are pictures.

But today… I don’t think about this process very often, because for me it’s absurd. These photo sessions don’t really exist for me. It’s something outside of life, supra-life, and this supra-life is like a dream. It’s very hard for me to think about the process now. I can speak for a whole day about Carnival and rituals, but about this process? My motivation, and their motivation… it’s very, very difficult to live with these thoughts.

Last year, I was thinking a lot about this work, about myself, about my projects in general. And I fear this project destroyed something in me. Like, it destroyed my juvenility. Maybe I made this work too young – I was 23. My body and mind don’t connect anymore. I saw something very trivial, very rude, and maybe this broke something.

I went to these sessions very young, very pure – like an angel! – with my camera. And, the men are all old men, 40 or 50, so they’re in a kind of transition. A life transition. And maybe they are excited by a young person. It’s a strange relationship, because they need me, and I need them. And I didn’t control their actions, I only offered to them all the possibilities. I offered the time and the session, and sometimes… they take me inside something I don’t really want to see!

But I also don’t want to control it, because I want the devil to appear, and to observe it and to capture it, and after two hours he disappears. And I don’t want to control the models, because it’s their time and their freedom, but maybe they gave me too much.

Could it be that if you are facilitating this ritual of their purification, serving as the channel, that you are absorbing some of the impurity?

I want to observe the monsters, and monstrosity is very dangerous. Rituals are dangerous for a non-initiated person, and the first session was very difficult for me because I entered an unknown world. I entered something very new, something very special, something very secret. It’s hard to keep all the secrets, and to live with it, because you are alone with this secret. It’s a lot of pressure. It’s like Pandora’s box, it’s very dangerous but it’s fascinating.

But you publish the photographs. It may be a secret meeting, but with the knowledge that you will share it afterward.

Yes, of course. And the photograph is very important to these sessions, because they immortalize the devil. They capture it.

You said that something in you broke because of this experience. How do you think you were changed?

Maybe I didn’t break something and instead I built something. But I feel broken. Maybe because it’s the start of something new: I feel like there was the death of something, but I have no rebirth. I don’t have any reference point anymore. I lost my feet. Maybe it’s this.

But I’m certain something changed because I saw a lot of sadness. I saw some pathetic humans, I saw some very sad people, some prisoners of society. And it’s very sad to see this, to see people who are prisoners of their lives. It’s sad to see people whose lives think for them, instead of the inverse. We have to think our life, we have to build it, we have to sculpt life. And time. We have to do something interesting with time. We have no time.

No? We don’t have time?

No! We have no time.

We have time right now.

Now? Yes, yes, but in life, we have no time. It’s too short, it’s just a quick gasp.

It feels very long to me.

Yes, maybe. But I’m afraid of time, of not being who I want to be. I’m afraid of it. Time and regrets – oh, it’s horrible.

Isn’t the solution what you already described: you sculpt life. And you become closer and closer to the person you want to be.

Yes, but to sculpt our life takes time, and it takes energy. It’s difficult, and there are so many ways to make life easy, like putting on the television.

A myth that comes to mind is St. George and the dragon. He took a grave risk to fight the dragon. St. George braved death, but for me, death is inactivity. It’s immobility. Death for me is a human state like a zombie. It’s dead, but alive. Alive, but dead.

Do you think you are at risk of being a zombie?

Yes! Yes, maybe in twenty years, or even in one year, I will be tired. Tired to always be…

Fighting a dragon?

Yes! It takes time and energy, and maybe one day I will be tired of this. Tired of the devil, tired of the dragon.

And maybe in twenty years it will be you, who is the old man with a devil he needs to release?

Maybe. Because, I spoke about television as an easy way of life, but society gives us an easy way of life. Like an Ikea table. It’s so simple! Get a table and yeah! you can be happy together with your wife and children. For me, it’s such an easy way out of life. It’s like a kids’ life. Poof! and you are happy.

In this project, I saw some sad people who were very afraid of having a transgressive life. A subversive one. They can be transgressive for two hours, but… for their whole life? It’s another question.

Kissing Madness: An Interview with Pierre Liebaert was first published in GUP#49, the Intimacy issue and later as an extended interview on GUP’s website. Liebaert also produced Free Now as a short film, which can be viewed on his website: pierreliebaert.com/film