In Becoming Creative, Juniper Hill speaks to musicians in Los Angeles, Cape Town and Helsinki about their personal histories, experiences, and viewpoints to trace patterns of creation.

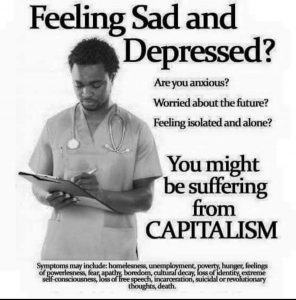

Pathologies of Capitalism: An Interview with Michael Arfken

Dr. Michael Arfken is a psychology professor at the University of Prince Edward Island, with specialties in phenomenology, sustainability and ecopsychology, among others. One of his ongoing interests is the relationship between capitalism and psychology, which he’s argued are codependent bedfellows. He’s organizing a conference that takes place in New York later this year, “Pathologies of Capitalism: Critical Psychology in the Age of Uncertainty,” at which scholars will present findings from their various fields of inquiry. Arfken speaks with us here about capitalism, community, and the value of protecting authentic experiences.

Explain a little about the name of this conference, Pathologies of Capitalism. Where are you coming from?

This extends from a previous conference I organized in 2010 on Marxism in psychology, and after some early debate on the development of the idea, we decided to include Marxism as one perspective of many into what we’re referring to is the pathologies of capitalism. Each speaker will be able to present ideas from their work as relates to four themes: Systems of Oppression and Privilege, Neoliberal Practices and Knowledge Systems, Colonizing Space and Place, and What Is to be Done.

The “pathologies of capitalism” is simply a way of linking research in critical psychology with the existing economic structure of society, and saying a lot of the things that people deal with in psychology that are treated as individual pathologies, we think are more a product of the economic structure in which we’re embedded, namely advanced capitalism. So, as critical scholars, we’re asking ourselves how can we engage with this and say something interesting, especially at this critical time. For me, this took on a certain urgency given the last U.S. presidential election, where we didn’t have a particularly good group of candidates to choose from in terms of electoral politics and where we also had the emergence of a candidate who unabashedly talked about being a socialist—which is a really big movement in American political history, which created a generational shift in what that the term means. So, it just seem like a really exciting time to explore these ideas, particularly in the belly of the beast; I mean you can’t get any more capitalist than Manhattan.

What are those signs of pathology?

In my own work, I think the very notion of a psychology is pathological. The very idea of psychology is just a euphemism for alienation. Modern psychology in research and practice takes on many of the same assumptions that organize the capitalist mode of production: the focus on the individual, the setting of the individual at the center and moving out into the social reality, rather than beginning with the social and how that constitutes whatever we call the individual now.

The very idea of psychology is just a euphemism for alienation.

Let me give you an example. I just met with one of my former honor students and she was talking about attachment theory, roughly about how the early childhood relationships that you have especially with your primary care giver shape your understanding of future relationships. She’s Canadian and was down doing her grad school down in the States. She was teaching a developmental course and talking about attachment theory, and said something to her students about children going into day care “after the 9-month maternity leave,” and the impact of that, and the students had no idea what she was talking about. They said day care started at 3- or 4-weeks old. She thought that had to be wrong, because she’s Canadian, which has protected maternity leave. However, the U.S. does not. So, the implications of this really blew my mind. Thinking of attachment theory, if you had an entire society where people were not given those primary early childhood experiences and were instead shipped off to day care, because of the need to generate income, at 3- and 4-weeks old, you would develop an entire society and generation of people with really insecure, maladaptive attachment behaviors… and it would look a lot like the United States as it is now.

So, I’m actually interrogating the notion of psychology itself, and how psychology and capitalism form a symbiotic relationship. They’ve evolved together and reproduce one another.

Canada is capitalist, too, though. So using this example, how do we explain the difference between the way capitalism materializes in two neighbors?

The difference is that Canada is a modestly stronger welfare state, and so that’s where the example of attachment theory could materialize within two capitalist frameworks. For me personally, I like to move beyond that sort of specificity and ask what is it about capitalism in general, whether you have a weak or strong welfare state, that creates certain types of people or creates people with certain types of expectations and encourages people to think about themselves in particular sorts of ways.

When you bring this within modern times, you have what’s sometimes referred to as “the entrepreneurial self.” It’s the idea that we have become entrepreneurs of ourselves: we’re selling ourselves or we’re understanding ourselves in market terms or in terms of human capital. We have all these market capitalist narratives that structure the way we make sense of our everyday lives. People haven’t always experienced themselves in this way, so where did that come from? And, how has that contributed to the type of people that we are and how does that reinforce a particular way of engaging with one another?

How do we achieve decommodification? Or, how do we decouple labor and the market forces?

One of the ways I try engaging with decommodification is through an ecopsychology course that I teach. One of the things the students do throughout the semester is to learn to make the things that they typically buy. We use a book about “radical home ec,” and it gets people thinking about what it’s like to make the household things that we use on a daily basis, whether it’s cosmetics or toothpaste or dryer balls—I mean, just ridiculous shit. We get something out of creating, but under capitalism, most of the things that we create are for other people and they tend to be under coercion, so they tend to be things we create not because we want to but because we have to survive.

So, in the process of decommodification, you try to take incremental steps outside of a market economy, you start to make things yourself, just take note of how you become different as a person. At that point, you’re moving in the direction of what philosopher Kate Soper referred to as “alternative hedonism,” the idea that you can derive pleasure from these really simple, basic forms of engagement.

This isn’t about giving up Facebook or some other technology, but about becoming full people.

Now, at this point, most people say: You just want to go back to living in a cave, you’re not a part of progress, you’re taking a romantic view, you’re not moving forward in the way that we should be moving forward as society and as a people, and so forth. But you eventually come to realize that all the steps forward that we’re taking come with a cost in terms of the type of people that we become. And once you start to engage in these types of practices, and enjoy them and simplify your life in certain sorts of ways, you start to realize that you’re not giving up things, you’re actually gaining things. This isn’t about giving up Facebook or some other technology, but about becoming full people.

Marx said, under capitalism, we’re in our pre-history. So then, what does it mean to be people in the full sense of the term? What does it mean to become these entities that we thought we were, but we haven’t yet become? I think once you realize it’s a game, and there’s room to play in these different types of practices, you can create a movement of people who are willing to step outside of a traditional market economy.

Are there not only full people but full societies?

A sociologist named Szasz has a notion called, “inverted quarantine,” to describe the way we tend to deal with issues today. If we’re concerned about water, we get bottled water. Back in the ‘50s, if we were concerned about war, we made a bomb shelter. We find individual, consumer solutions in order to address our problems. That’s an inverted quarantine. A quarantine is where a situation where someone has an issue and you put a bubble around them to protect everyone else; an inverted quarantine is where you see an issue and put a bubble around yourself to protect you. I think we have all sorts of problems within our society today and we’ve been taught through a consumer culture to purchase our way out of those problems to protect ourselves as individuals. I think once you start getting together with other people as communities, you start to look for community solutions, and you start to look outside of market solutions that protect individuals and look for community solutions that protect everyone. So, it’s just shifting our way of thinking about these things.

How do you arrive there without taking things away?

It’s not about taking things away, but realizing that there are other ways to do things. For example, social media. Part of the reason I never got on social media is that I got mad that I was being told that this is what a social relationship looks like now: if I want to be “social,” this is how it’s done now. I find that really, really offensive. I’d much rather speak to you as we do now, once every three years, than see what you’re eating for breakfast on a daily basis and make you feel uncomfortable because I didn’t “like” it. We need to step back and see what our world has become.

People in our generation have a particular responsibility to the younger generation in helping them navigate this, because you and I were at this point where we saw the before and after. We didn’t have email and internet, and then we did. We lived in both worlds, and so I think we take on a particular responsibility for helping other people understand that the way things are today, they don’t have to be that way.

We need to step back and see what our world has become.

Getting back to what it means to be a “full person,” I feel like there’s a lot of pollution around the word “authenticity,” or what it means to be “real.” Are there such things as real versus unreal experiences, and if so what do they look like?

Yes, there are, and it’s important to keep alive the distinction between real and unreal, or authentic and inauthentic, because once you start to blur the boundary—and people heap a lot of scorn on postmodernism for doing this—you don’t have anything to fight for. If everything is just unreal, then anything can be just as good as anything else. So, I think it’s important to keep that notion of authenticity alive. By the same token, you have to be sensitive and vigilant about how those words are being appropriated. The vacation industry is a good example of fabricating “authentic” experiences, but even when you get into cultural politics, you have people trying to defend, for example, what it means to be a “real” Indian. That is, neoliberalism is accused of destroying what it means to be an Indian, but to figure out if that’s the case, you have to ask questions like, what does it even mean to be Indian? Well, what are the parameters of Indian-ness? What flexibility is there to step outside what it means to be Indian, and who gets to decide what constitutes proper Indian versus non-Indian behavior? So, it cuts both ways, and there’s no easy way of navigating that, but I think the last thing you want to do is get rid of the notion of authenticity.

What do you think then are the signals or symbols that you’re going in the right direction of authenticity?

If you’re not paying for it, that’s a good indication. I think if whatever you’re doing plays some role in reducing human suffering, there’s something authentic about that, and if you’re doing something that increases human suffering, there might be something inauthentic about that. I do think there’s an ethic around it, for sure, and it’s not a complicated ethic.

There’s a philosopher, Albert Borgmann, who talked about the notion of “focal practices.” He says, when you’re involved in a focal practice, you should be able to affirm the following four statements: There’s nothing I’d rather be doing. There’s no one I’d rather be doing this with. There’s no place I’d rather be. And, I will remember this well.

If you can affirm all those four statements, you’re involved in a focal practice, and that is to me a good barometer of authenticity.

Let’s talk about post-productivism, which is I think still a bit of a fringe concept, so maybe you can start by just laying it out as you understand it.

Let’s start by explaining that the aim of capitalism is to develop the productive forces of society. So, within society you have a certain amount of productive forces, and through the capitalist mode of production, you aim to increase efficiencies so you can increase the productive level of society. For example, I had to clear the weeds on my property, and if I just had a rake that would take me forever, so I take my fuel-powered car to get to a shop and rent a gas-powered weed whacker. Through capitalism, you can create efficiencies and develop technologies that make people have to use less work in order to do something.

Now, the promise at every step of that, is that once the next level of tech comes into existence, we won’t have to work as much. We’ll create these technologies, and eventually we’ll get to sit back and our inventions are going to do the work. Well, of course that’s never happened. What’s happened is that these new technologies have been used to increase the pace of work. So, you end up working just as hard, if not harder, and producing a tremendous amount more than ever could’ve been produced before, and that tremendous production is then appropriated by those who own the means of production in order to lead to the gross inequality and wealth that we see in our present age.

New technologies have just been used to increase the pace of work. So, you end up working just as hard, if not harder.

The idea behind post-productivism is about recognizing that we already have a greater ability to produce things than has ever existed in our world, and seeing ways to reduce or eliminate coerced work. How can we use the productive forces of society, which have been built collectively, not for the benefit of the few but for the benefit of everybody?

These are systematic forces at play though, so what are my responsibilities as an individual, or how can I affect this?

Any system that we have was created by us, so I think we as people have a responsibility to produce systems that are to the benefit of the greater part of humanity and destroy systems that aren’t. Post-productivism asserts that we can reorganize systems in such a way that they’re to the benefit of the greater part of humanity.

Well, can I as an individual overthrow or destroy a system?

No, I think it has to be done collectively.

This gets back to your argument that the pathologies of capitalism don’t exist in our mind, but in the social relations of modern society. How do social relationships “contain” ideas or beliefs?

The metaphor that I normally use, drawing on other scholars, is the distinction between the map and the territory. The territory is our concrete everyday experience, and the map is the representation of that territory. The argument I make in some of my work is that we’ve moved away from everyday, concrete interactions with one another into a society based simply on exchange of products that we’ve created through our labor, or that we sell our labor on an actual labor market. Marx refers to this as “commodity fetishism.”

The idea is that we live in an abstract world. And you see this in psychological theory—most theories in psychology involve some degree of what’s referred to as “indirect perception.” So, I’m not encountering you, I’m encountering my representation of you, and you’re encountering your representation of me. What I argue is that is not a feature of basic psychological functioning, it’s a feature of living within a particular commodity-dominated society. So, psychology itself, as an institution, is just a mechanism of capitalism.

There’s a difference between a real and a non-real conversation, right? Have you ever sat down and talked with somebody and you didn’t want it to end, and there was something about a to-and-fro where you weren’t trying to assert your own opinion or dominate, but you took some subject matter and played with it? In that process of engagement, you feel the difference, and in that sort of real conversation, it betrays the irreality of most of our everyday interactions.

Right, but those are typically peak states, rather than something we can just connect to instantly. It takes a certain amount of scaffolding.

I think some of us find ourselves in positions where we have more time and more ability to do that.

Well, I want to walk this back a bit, actually. Some people argue that their experiences are somehow more real than other people’s, or that they know what “real” is and other people don’t, and I don’t think that’s valid. This is arrogance.

Yeah, I agree and I think that’s to be avoided. We all have the potential to experience this, and in our moments we do experience them, but what I’m saying is that within a certain economic structure, it’s designed to either not let us have those experience or to substitute inauthentic ones for authentic ones, and that’s something to be resisted. I mean, if everyone can tell the difference between having that experience and not, I don’t think anyone would ever accept one over the other.

Yet people often do accept one over the other, simply because it’s a peak state that requires a lot of scaffolding to get there. You can’t just say, “I’m going to have a real moment now,” you have to set up circumstances around you to allow that to flourish.

I totally agree with that, and I want to argue that capitalism is not that scaffolding, to use your metaphor. And socialism is.

Why?

Socialism is oriented to meeting human needs rather than generating profit, and that’s the sort of scaffolding you need for those sorts of authentic experiences. I think socialism provides the background conditions against which human flourishing and full human potential can be reached.

So, let’s think about the relationship between work, jobs, income, and purpose. How do we pull these apart from one another?

I think we start by taking an inventory of the things that we need and the things that we don’t. And, of the things we think we need, how many were produced? This helps us better understand how much of that need is really propaganda. Once we realize that the things that we want, we don’t actually need—our authentic versus unauthentic needs—we can start rebuilding.

You see this phenomenon in transition towns. They organize as communities in order to build up an infrastructure where they can continue to exist and flourish in a post-non-renewable society. Oftentimes that revolves around simplicity in certain areas, but not all, a reduction in consumerism, and focusing on community… things like that. It doesn’t mean being that person who goes to live off in the woods in a cabin by themselves, it involves doing this at a community level.

Another thing, modern social justice struggles have been largely oriented along the ideas of identity, which is really important in certain respects and has done a lot of good in a number of areas, but has also created a really big divisiveness. I think we need to integrate within modern social justice struggles a bigger critique of economic injustice, and not just by increasing the welfare state but by actually challenging the capitalist mode of production itself, which I think can be a very unifying rather than a divisive sort of politics. That needs to become a part of a social justice struggles in a way they haven’t been in the past, which is why what we saw with Bernie Sanders in the last election was very inspiring.

Once we realize that the things that we want, we don’t actually need, we can start rebuilding.

As a university professor, you’re dealing with the younger generation of emerging adults. Tell us, how do they receive these types of ideas? What’s the temperature?

It’s cold. (laughs) I haven’t found my students to be terribly engaged on these issues. A couple of them really take this stuff and get excited about it, but by and large, reflecting on my own experience of teaching… students are wrapped up with this stuff. I mean, they’re plugged in.

It kills me to see the way that social media has colonized their way of understanding themselves and relationships. I can’t even get students to talk to me; they feel more comfortable sending an email than actually talking to me in person. That’s something we need to work on. And it’s something I work on in my courses, like with the ecopsychology course. But for students today, university is an interesting thing. I mean, there’s no guaranteed job, especially not in psychology. A lot of people are in university because of the cultural narrative that this is the next thing you’re supposed to be doing in your lives, you know? This is the story. This is the way one lives one’s life. I try in my classes to directly interrogate that, but it’s a struggle.

Is there possibly a “gateway drug” for socialism? Something that breaks the resistance that makes it seem not just palatable, but an actual way of life?

These make-it-yourself projects that students do in my class seem to work. Once they get a taste of that, and they start working with other people, it opens up a whole new world for them. Some of them tell me how they’ve started making things for their family and friends, as well as themselves. It’s getting people to realize they’re capable of more than they think they are.

Not everyone wants to move out to the country though. How do you take the best of a technologically advanced society and leave out the parts that eat us up?

In my life lately, I’ve been thinking about cycles. Things just move in cycles, and the older you get the more you start to see those cycles. A lot of the joy I’ve found lately is finding cycles in various places and inserting myself into those cycles, not to dominate but just to participate within them.

For example, I have chickens now, and I compost and farm. I feed my chickens our scraps, they give us eggs that we then eat, then the chickens poop and I put it on the compost, together with our other scraps, that creates new soil that I feed to the vegetables that then grow up that I feed to chickens. In homesteading you see it a lot, but you can find cycles in every part of your existence. I can see it in my learning and teaching, I can see it with my kids. The more that I participate in cycles, it’s like I’m preparing for my own death—in a positive way. The more I do that, the more I see myself as part of a larger cycle, and know that now I’m going to do this, and then I’m going to not be here, and I don’t know what’s going to happen then, but these things will continue.

Learn more about Michael Arfken on his website.