Join me for a photo workshop in France and soak in the pleasures of photography, food and wine.

Too Tired for Sunshine: An Interview with Tara Wray

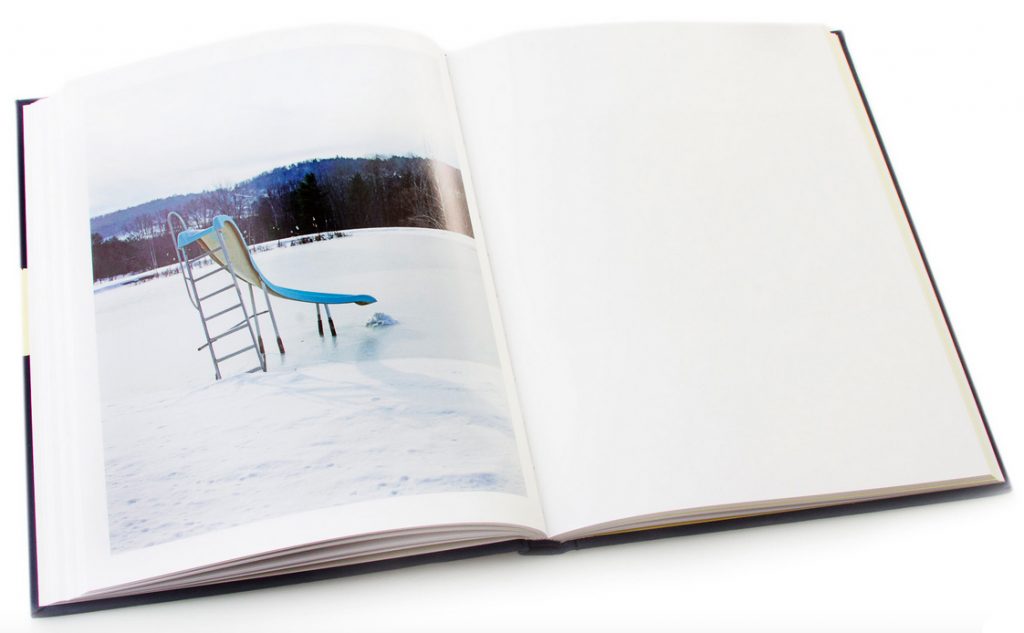

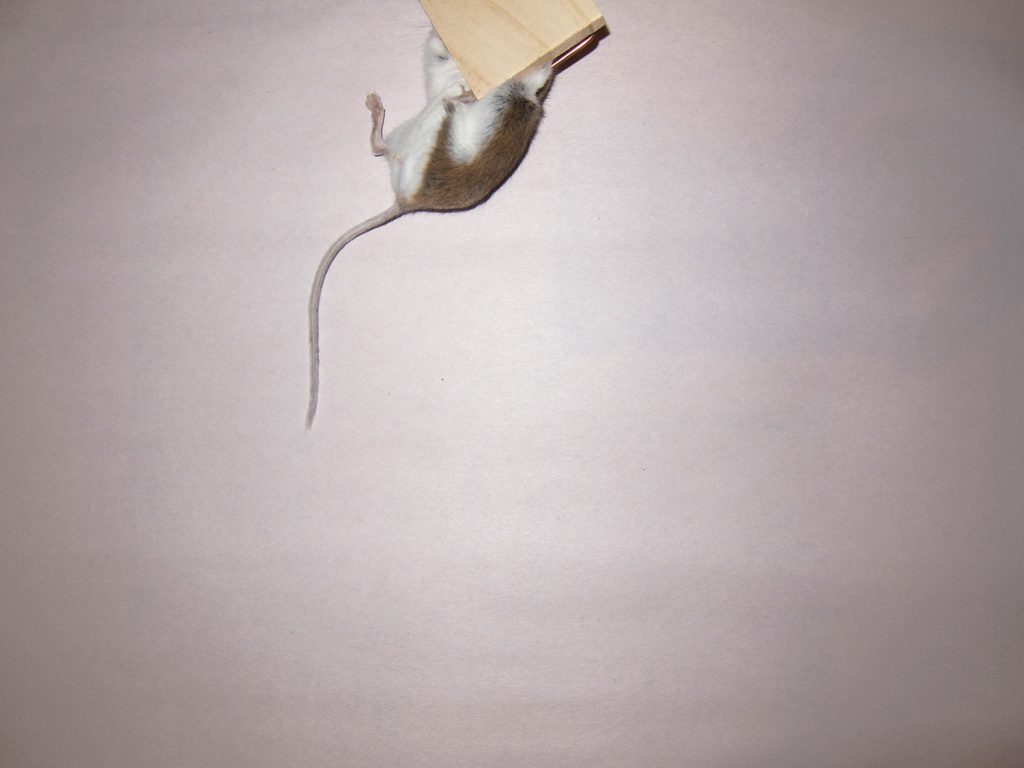

American photographer Tara Wray is too tired. Too tired for sheepish dogs, too tired for playgrounds in winter, too tired for flowers. At the heart of her photobook Too Tired for Sunshine is an exploration through the exhaustion of depression. Yet it’s not all doom and gloom: Wray’s observational photographs bear a wry smile, with each joyful object imbued with a bit of sorrow and each lonely scene managing a touch of the playful. Her book hit a nerve, and has since become the dark horse catalyst for a movement: photographers worldwide who also express depression through their images contribute collectively to the Too Tired Project. In this interview, Wray speaks about the project, the grey area between the therapy of art and art therapy, and her own relationship with creation and depression.

American photographer Tara Wray is too tired. Too tired for sheepish dogs, too tired for playgrounds in winter, too tired for flowers. At the heart of her photobook Too Tired for Sunshine is an exploration through the exhaustion of depression. Yet it’s not all doom and gloom: Wray’s observational photographs bear a wry smile, with each joyful object imbued with a bit of sorrow and each lonely scene managing a touch of the playful. Her book hit a nerve, and has since become the dark horse catalyst for a movement: photographers worldwide who also express depression through their images contribute collectively to the Too Tired Project. In this interview, Wray speaks about the project, the grey area between the therapy of art and art therapy, and her own relationship with creation and depression.

You describe the Too Tired Project as a “photography initiative committed to helping those struggling with depression by offering a place for collective creative expression.” How did your own work transform into this community project?

I started the project in 2018, about a month after my book Too Tired for Sunshine came out, and it was essentially a response to people writing to tell me that they had seen my book and that they used photography in the same way. I couldn’t really find anywhere online that provided an outlet like that, and so I came up with this idea around 2 o’clock in the afternoon and by 5 o’clock that night had started the Too Tired Project Instagram, and it hasn’t stopped since then. People submit their work using the hashtag #tootiredproject and share some words about how it relates to depression, and that can be as oblique or head-on as they want it to be.

Then, in March of this year, Polish photographer Zuzanna Szarek joined as art and communications director, and she’s been doing a ton of work with me on everything from the slideshows to curating the Instagram to finding artists for the Sunday Spotlight series, and was instrumental in organizing the #tootiredwarsaw slideshow at Leica Gallery.

Do you set curatorial guidelines for the project or do you see it as a public podium for all who care to share?

Both. Being really interested in photography, my first thought is to ask, “Is it a good photograph?” but there are also times when I’ve published sort of an “amateur” photograph with a story that’s incredibly powerful and is bigger than the picture. So, the Instagram is a combination of both, though now we’re expanding into other platforms that take other approaches. We do slideshows, which are essentially photo exhibitions, so I definitely want the level of work to be pretty high, and also, because there’s no text, the image does have to speak for itself. I’m also going to do a book of the work, and I certainly have expectations for a pretty high level of photography with that.

What sort of stories grab you?

Sometimes it’s just recognizing somebody sharing a truth that maybe they haven’t shared elsewhere. Why we put these things on the internet at all, I don’t know, I’m not the person to figure that out, but that’s what we do as a species now. There’s so much garbage, so much negativity, and so much fear online—I mean it’s really the wild, wild west—and so I’ve tried to carve out a place that’s non-judgmental and welcoming. It’s not a place for any kind of hate, and I think people respond to that by sharing something that’s as real as you can get online.

You said people reached out to you when they found your book. What did they say to you that made you realize this was needed?

It’s hard for me to say, because I don’t really like saying about myself the kind of things they said, like, people thanking me for sharing my story and for being brave. I don’t necessarily think of myself as brave at all, I’m a pretty anxious and shy person until you get to know me. It just seemed necessary; I couldn’t hold all the things that people were saying to me on my own, and some of it got pretty serious and pretty dark. People were telling me that I was the one who could understand them, and that can be intimidating, certainly, when you’re going through your own shit!

But it seems like this space that I’ve created has become a place where people can in some small way depend on each other, even if just for a second. I mean, it’s all scrolling and likes, but I think there is a real connection. People tell me there is.

Let’s talk about your book, Too Tired for Sunshine, since it was basically the catalyst for all of this. You started with shooting, rather than with a project in mind. At what point did you realize you had a project?

August of 2016. That summer and fall I had a lot of anxiety, sensing the direction the country was heading and feeling like I needed to gather my thoughts and assess what I had been doing. It was probably a little dramatic, the way I was thinking—Oh my god, this political event is coming and we need to prepare by creating work!—but that was part of it. I went through all the photos I had made in the past eight years, from the time I had learned to use a camera, and printed out a whole bunch, put them on my floor, and just started moving them around like Tetris, trying to find connections and throwing things out that I loved but that didn’t work in any other way other than being a pretty picture. So, I really started thinking about it as a book around that time.

Once I decided how the pictures fit together and thought about what was going on in my mind when I took some of them, I saw the connection: I very often photograph things that represent my emotional moment and a lot of those moments were pretty dark, but they were also absurd and funny and scary and sad—all the things that life can be. That was pretty much the end of 2016 and the book came out in the summer of 2018, so it was a bit of a hike but really worth it.

In describing it, you sound self-assured about what it is, but the subject matter you’re working with is rather abstract. Did you have to do some internal negotiating on what it meant?

I mean, I still do that. The book is out—and even sold out—but I don’t think I’ll ever stop that negotiation. It’s just how I operate. It takes time to tease out the narrative obviously, and doing that with an editor and a publisher helps clarify it, but I know what my work is about in this book because I lived it and it’s mine, you know? I don’t think that negotiation ever ends but when something is out in the world it’s really hard to put it back.

People often comment on the “dark humor” of your work, and the title especially strikes me as dark humor if not fully ironic. You’re saying you’re “too tired,” but there’s a certain frenetic energy required for all the activities of producing the work, editing the work, creating a publication, and so forth. How did you get this project off the ground?

That’s part of the beauty of making the work over such a long period of time; I could’ve taken one picture in June and not made another one until September. The doing of the project gave me energy and life and purpose and all those things that I’m not feeling on the days when I’m too tired. It’s a self-perpetuating project, so, the more I do, the more I want to do. There are definitely days when I don’t have the energy, and today is a day I’m struggling. It’s been a shitty day and I’m glad I forgot that you were calling me today or I would have been sitting and ruminating over it for hours and, instead, I didn’t even brush my hair! [laughs] It really is fighting every day and the project gives me something to fight for in a productive way that’s bigger than myself, which seems to be good for me.

Let’s stick on this point of it being a self-perpetuating cycle because I think a lot of people resonate with that. If you’re already in motion it’s usually easier to keep going, but what happens when you have no energy? How do you get things moving?

I’ve been fighting with that. You know, part of what’s difficult about this project is that now I’ve put myself in a position where I have to talk about myself in this way. I talk about the fact that I take medication, and if I get to a point where I’m too tired, I’ll look at adjusting my medication. I’ll look at how I’m eating or if I’m exercising or sleeping. I look at all these things constantly; like spinning plates on a stick, you’re always monitoring just to stay at a certain level. I’m 40 years old so I know a little better when I’m dipping and what to look for and how to head it off. It’s just an awareness. It’s a mindfulness a lot like making photos—you focus your energy and pay attention to your surroundings, what you’re feeling, what you see, and how the world around you is responding. It’s the same as dealing with mental health for me. I have days when I don’t take out my camera just as I have days when I don’t want to get out of bed. It’s all part of the same continuum.

You said in an interview that “Photography had been taking care of me in ways that I wasn’t always conscious of.” How so?

Well, I think in some ways it’s a comfort blanket. Having my camera gives me something to do with my hands and gives me a reason to be somewhere that I wouldn’t be otherwise. It helps me feel less awkward in a way because I can focus on that instead. It’s just a tool, really, for me to take care of myself and try to understand myself. Photography is my friend, I don’t know how else to say it. It’s a vital, important, necessary piece of my life.

Do you see a distinction between the therapeutic value of making art and what’s called “art therapy”? What elevates the work to something worth sharing?

That’s a tough one, because some part of me considers myself an artist—wants to be an artist. I want to make work that is at a level that you maybe wouldn’t see if you were in an art therapy class producing work just to say something that you couldn’t say. That’s a tough question that I’m dealing with on the Instagram project, too. Is this art? Is this therapy? Is it both—can it be both? I think the work produced from art therapy could be seen as “less than” in an art world setting, but it’s not really meant to be in that setting. I wouldn’t want to criticize anybody’s work that was made in a therapeutic setting as not being art because it has a different intention.

For myself, I want to make photography that speaks about myself and my world, and I want it to be bigger than me. Maybe an art therapy class is about discovering something, but that’s the same as what I’m doing. So, it’s very much connected.

View this post on Instagram

Submission from @annapaulinefranz for @tootiredproject #Repost @annapaulinefranz ・・・ 👛 #hundredyears

What is the range of work that you receive through the hashtag submissions?

Well, it’s Instagram, so it really runs the gamut. It’s coming from all ages, all over the world. Sometimes people just use the hashtag because it’s suggested and they may not know anything about the project or what it means, and that’s fine. I see every submission, and a good portion of it comes from photographers who I know personally and I’ve asked to consider taking part. It’s a delicate thing to even pitch—Is your work in some way related to depression?—but pretty much everybody I’ve written to has said in some way that their work fits. It doesn’t have to be straight on, like, “this is a photo of my depression,” it could be, “my mother is depressed and this has trickled down to my life and the work I make.” It’s all related. I don’t know anybody who hasn’t been touched in some way by mental illness, directly or indirectly.

In terms of the photos, you get a lot of people sitting in bathtubs, a lot of backs… there’s definitely an aesthetic when people think of pictures of depression, but I’m trying to look beyond that and find the unexpected pictures. In any case, I think it’s important to say that I’m really proud of the work that’s on there and I’m proud of the people who have shared. I also know photographers who have said they’re not ready for this yet, but when they get there they’ll share, because they get what I’m doing and say it’s… [pauses] important.

The way you paused… I can see you still don’t like to think of yourself as brave, even at the same time that you compliment others for their braveness in sharing. I think it’s important to underscore that it takes vulnerability to put these things out into the world, because even though depression is very common, it still carries a lot of shame and embarrassment.

For sure, and I still struggle with that. That’s one of the things that I really hope to bring to light: if I can get through it then maybe other people can, too. It’s not something I talk about with everyone in the real world but I do when I go online; it’s kind of a strange paradox.

How do you think of your own relationship between your emotions and your creation? Are there some states in which you can or can’t produce work?

No, it’s totally inconsistent. And that’s frustrating. Sometimes I just feel more attuned to the world and I’m seeing it in a way where everything could be photographed, and then other times, I’m just like… I can’t do this. My kids are screaming in the back seat, I have to figure out dinner, I’ve got a sick dog…

There’s life and then there’s art, and sometimes they converge and work together and sometimes neither of them work. That’s definitely a struggle.

Last summer I went to Kansas to work on a project—which was far removed from anything I’ve done before, it was a collaboration with a poet who was writing restaurant reviews of mid-American chain restaurants. Taking those photos took me back to Kansas, which is where I’m from. That was my initial excuse for even contacting the poet and saying, “Hey, can I make photos for these poems?” That was amazing. It was just a few days and I took thousands of pictures. Things like ants crawling on french fries were really exciting to me; I saw that as a picture, whereas today I don’t know that I would. I had a heightened sense of excitement and awareness and clarity—which doesn’t come very often, so it was kind of a wonderful little photographic and creative respite.

But you don’t see a pattern or predictability regarding what emotional states work…

No. It’s kind of a mystery. I think it works if I have my camera out. That’s the truth of the matter.

Do you see any difference in the modes of making art versus editing?

I like editing. I read everywhere that photographers are not good editors, but I think curating the Too Tired Project has given me an editing insight. I like finding the connections and putting things together. You can have an image that is nice, but when you put it next to something else it tells a whole story. Finding those moments is really rewarding.

When it comes to creating, I can’t really go out with the idea of making work; it finds me and if I have my camera ready then it’s a match. With editing it’s different; there’s a kind of a mindlessness to it, you’re just going through work—no, no, no, yeah—and that appeals to me. Sometimes I just need that. I like the tangible part of it too, when you put the pictures physically in your hands and move them around. There’s something meditative about it.

I also like looking at old pictures in this way: it gives me that time back. If it was a dark moment, I can look at that today and think, I got through it, but I like how you can move it around in your hands and have a different experience with your past.

You’ve said before that “being healthy is a process.” What does that mean to you?

I think it means paying attention to my environment and to where I’m at in my thinking patterns. Sometimes I can get into a loop of negativity or fear or shame or anxiety or depression or whatever, and if I get too far into it, it’s hard to get out, so it’s a lot easier when I can cut it off at the pass. That requires a lot of mental energy, just staying focused and knowing how I’m doing. I don’t think everyone struggles with this, I think some people just go through life, but for people like me it can be a slog and a challenge.

I’m at a better place now then I’ve probably ever been, and that’s because I’m staying on top of meds and food, and—alright, my exercise routine has gone to shit but I’m trying not to beat myself up about it. I have eight-year-old twin boys and that requires just a phenomenal amount of physical and emotional energy, and I’m trying to help them do the things that I’m struggling to do, like managing frustration and anger… I don’t even know how to do that! But I’m trying to teach them. So, it’s a process. It’s a job.

I don’t know what it would be like to wake up in the morning and go through life as a person who just moves through the world without any of this daily necessary mental work, but I know what the alternative is and it’s not good. So, I’ll put in the work because I have to be healthy for myself and for my family and for my work. There are some red flags I should be paying attention to in my own life, and I am, but there’s only so much you can do.

Considering you said you’re now in a good place, what is the best advice you would give to yourself when you’re too tired for sunshine?

Don’t give in to it. Sometimes settling in the misery is easy and comfortable but don’t give into it. Just put one foot in front of the other, just do the little things, and then everything’s opened up.

That would be my advice to myself… whether or not I would listen to myself, I don’t know. Probably not.

As you said, it requires a lot of physical and mental energy to do it…

But they’re necessary. It’s necessary. An athlete trains, so does somebody who’s dealing with chronic things like depression and anxiety.

Have you heard any other words of wisdom from all the people who are submitting to the project and telling their stories?

I did hear one recently. When you’re in anxiety—in an anxious moment—and your brain is telling you Panic! Panic! Panic!, it’s important to differentiate whether it’s anxiety or intuition. Anxiety is something future-focused that may or may not happen but that you can’t control, it just gives you something to spin out on, whereas intuition is something that you can act on. So, you should try to answer the question: is this intuition or anxiety?

The other day I pulled that out of my toolbox and was able to bring myself back, so that was really useful, and then I passed it on to someone else. I mean, I don’t want to be a self-help network but I did find that useful and practical.

Let’s get back to your own work. When you take into account the submissions that you get now and everything that’s been reflected back to you through feedback about what you’re doing, has that changed your photography?

It’s made me more self-conscious of my own work. I’m still looking at the same things that I’ve always been looking at—animals and dark myth and absurdity, that’s kind of my wheelhouse—but it has changed whether I actually take a photo. It’s a bit like writer’s block, I guess. So, I’ve been consciously telling myself to keep my camera out and just do the work. There’s so much self-consciousness even when you post a picture, whether it’s going to get liked or not. You get way too much in your own head. That’s another reason I like the camera, because it takes me out of all that, and I really am just looking and being present.

Again, though, I just want to express my gratitude to everyone who’s taking part in this, especially the people coming to the slideshows because that’s another level of commitment. You’re no longer just posting online but you’re in person sharing this part of yourself. I think that’s really the key point of the whole project, that taking part brings people together and makes things okay a little bit. Even briefly. I’m really just proud of everyone. For eight years, I was making sad little pictures on my own, and now I feel like the world is open to connection. I feel very lucky. I do.

Photographers can submit their work to the Too Tired Project on an ongoing basis using the hashtag #tootiredproject. The next slideshow will be Too Tired Melbourne on June 14, 2019, and submissions will be accepted until June 5. All submissions will also be considered for inclusion in Wray’s Too Tired Project book, forthcoming from Yoffy Press in 2020. See more information on Wray’s book, Too Tired for Sunshine (sold out), on her website.