"Maybe the ‘love’ metaphor is an interesting one; we shouldn’t fall in love with the future, it’s too dangerous. We need to keep a distance, have a mature relationship."—Andrew Keen, in our interview about his book How to Fix the Future

Putting Peer Pressure to Work A Review of Robert H. Frank's book Under the Influence, in the Time of Coronavirus

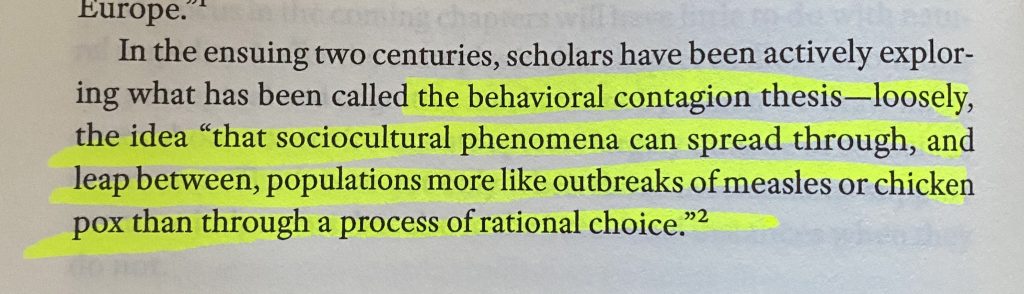

In the new book Under the Influence: Putting Peer Pressure to Work, economist Robert H. Frank makes the case that, given the powerful way that behavior is transmitted from one person to another to many more—a behavioral contagion, spreading much like an infectious disease—it is prudent to put this aspect of our humanity to good use. In particular, when the behavior that spreads has a negative impact on society, we have an interest in curtailing it, if not by influence then by law. While many complain about the overreach of mandated protections, crying out against the “nanny state” and for “individual liberty,” Frank argues these are not necessarily valid reasons against enforced collective action for good. After all, behavioral contagion is already put to plenty of poor use for antisocial gains.

In the new book Under the Influence: Putting Peer Pressure to Work, economist Robert H. Frank makes the case that, given the powerful way that behavior is transmitted from one person to another to many more—a behavioral contagion, spreading much like an infectious disease—it is prudent to put this aspect of our humanity to good use. In particular, when the behavior that spreads has a negative impact on society, we have an interest in curtailing it, if not by influence then by law. While many complain about the overreach of mandated protections, crying out against the “nanny state” and for “individual liberty,” Frank argues these are not necessarily valid reasons against enforced collective action for good. After all, behavioral contagion is already put to plenty of poor use for antisocial gains.

It is unsettlingly apropos that as I read the final pages of the book, and sit down to write this review, coronavirus escalates into a pandemic. Frank argues—much like the current news cycle—in favor of policies that we may as individuals be inclined to resist, but when mandated to the whole, benefit us all—not only as a herd but also as individuals. Take as an example a rule declaring that all ice hockey players must wear helmets: When not mandated, individual players may opt to not wear a helmet, to their own great risk, because it offers them an advantage over other players who do wear a helmet, yet when all players are mandated to wear a helmet, all are offered protection at no cost to competitive edge. Most importantly, even those players who opt not to wear a helmet are in favor of enacting helmet rules, because they understand the risk they’re taking on otherwise. Pair this thought with the articles published daily now, urgently pleading for people to act individually to reach a collective best interest—because it’s in your own best interest, too. Stay home, even if it’s inconvenient. Maintain social distance, even though it may be boring. Stop hoarding masks, you’re being a jerk and making it worse for everyone.

Frank’s book, Under the Influence, has nothing to do with coronavirus, nor any other biological contagion, and yet, the time in which we are living insists that I make the connection. We are in the midst of witnessing widescale behavioral contagion, of natures both bad and good: the rush on toilet paper somehow became a thing, spreading and escalating until shelves were emptied in multiple cities dotted around the world; meanwhile the concept of “social distancing” as a means of stopping the spread of the coronavirus by reducing contact with others has become a way of, ironically, showing solidarity through isolation. These are complex social behaviors, both coordinated and organically emergent, much like the ones discussed by Frank in his book.

“If social environments heavily influence our behavior, sometimes for the better but often for worse,” Frank writes, “it follows that the public has a legitimate interest in shaping individual behavior with an eye toward its impact on those environments.”

The primary example Frank uses to make his argument is smoking; this is because, he says, “It embodies perhaps the simplest and least controversial illustration of my case for public policies that influence the social contexts that shape our lives.” While people feel like they choose to smoke (or not) as free agents, Frank points out that, “By far the strongest predictor of whether someone will smoke is the percentage of her closest friends who smoke.” If one of your friends takes up smoking, they thus increase the odds that you and others in your circle will smoke, increasing the odds that other friends will smoke, and so on. “By far the greatest injury caused by someone’s decision to become a smoker is the harm caused by making others more likely to smoke as well,” Frank writes. Yet, because we believe that people have agency to choose their lives, we still struggle with the idea that it may not be the individual’s “choice” to smoke—we don’t blame others (usually) for our decision to take up smoking, and perhaps more importantly, we rarely are willing to take responsibility for other people’s decisions. As Frank puts it: “Even those who fully appreciate the extent to which our own behavior is influenced by peers have tended to ignore the significance of causal arrows running in the opposite direction: what we ourselves do also influences the behavior of others.”

Phenomena such as this demonstrate the curiosity that is humanity. We are animals with a strange kind of consciousness: we have sufficient sense-of-self to claim individual desires and to reflect on ourselves and to state that we are “independent” or “free-thinking”, yet we are also a highly social species that cooperates (at scales both small and large, on anything from a crossword puzzle to international air travel infrastructure) and that absorbs most information (about everything from moral concepts to fashion choices) from others rather than our own perceptions or earned knowledge. We are so accustomed to our pervasive social aspects—even the introverts and awkward among us—that it is difficult, if not impossible, to determine which of “my” beliefs, behaviors, thoughts, and knowledge actually originated in me. Likely very few. This flawed sense of individualism has many advantages, but it also, as we’re learning in high-speed alongside efforts to control the pandemic through public behavior, has many disadvantages.

In an article for The Atlantic, “The Shift Americans Must Make to Fight the Coronavirus,” Meghan O’Rourke argues that Americans (and I would extend that to include most Western nations) must shift their thinking “from an individual-first to a communitarian ethos.” While we may feel ourselves to be discrete entities, held separately by the boundary of our skin, she clarifies that, “the body is a social encounter, not just a vessel for our hyper-individualism.” If we consider the controversy generated by all social mandates when they’re first introduced, from smoking bans to universal healthcare or social security, it’s apparent that many people still believe themselves to be wholly self-contained. Perhaps it takes a pandemic to get through our thick me-skulls.

“It’s a different time right now,” mused Dr. Sanjay Gupta in an interview this week on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, “and I think what I’m really struck by is that never before—and I’ve been doing this for a long time—have I found a situation where how I behave so dramatically impacts your health, and how you behave so dramatically impacts my health and all the people [around us.]” Colbert was quick to point out that, particularly in the case of coronavirus, it’s not just a matter of the you and I who are present, but aging relatives, who are more at risk, also become part of the interaction. Gupta agreed, continuing: “That’s right, these concentric circles around you—that has to be important to me. I have an obligation now, not just for my health [and] my family’s health, but for your health and your family’s health. We are co-dependent on each other in a way I’ve never seen before. There’s an obligation now.”

The obligation, sometimes social convention and sometimes mandated by law, seems to be the only thing that curtails the contagion of unhealthy behavior. In Under the Influence, because Frank is an economist, the solution he proposes is fundamentally a practical one: tax antisocial behavior. It is a solution that has proven effective before—to return to his prime example, the taxation of cigarettes having led to reduced smoking—so he argues that we ought charge taxes for any activities that damage the environment. Frank early on names climate change as one of the most urgent matters of our time—something that, until coronavirus, seemed indisputable—and describes the tax approach needed to curb the behavior that otherwise will not self-regulate. Indeed, businesses often influence us in ways that we would not allow from the government, simply because they don’t hold the same burden of transparency and accountability to the public. Frank writes: “Businesses have fully grasped the power of peer influences and are heavily investing in new ways to harness them in the service of corporate goals.” He continues: “When it suits them, they deploy every weapon in the modern marketing arsenal to induce us to engage in deeply self-destructive behavior.” Meanwhile, when it comes to government policy introduced for social good, people cry “overreach.”

Frank takes a relatively philosophical question, whether public good ought to be mandated through policy, and breaks it down into its most practical parts: Are we actually influenced by others? Yes. Is that influence more positive or negative, on balance? More negative. Can we control this influence as individuals or does change only happen at the macro-societal level? Mainly the latter. What about personal responsibility? Well, behavior turns out to be mainly determined by environmental forces, rather than individual control. What do we do about it? Tax activities harmful to society and the world. Do those changes involve individual sacrifice? Actually, the end result is typically neutral or positive to the individual.

In the service of climate change, Frank makes a compelling argument not only for the effectiveness of public policy and a harm-based tax, but our obligation to enact it. However, he also demonstrates his belief in the significance of behavioral contagion by acknowledging his limitations: he alone cannot do it all, it will have to spread through the population. “If my ideas are to affect those debates, it will … have to be because others became motivated to continue talking about them.”

When I carry the message of Under the Influence into the immediate concerns of the day—that is, coronavirus—it becomes clear that social contagion will continue to be significant in shaping individual behavior, both healthy and unhealthy.

Most Western nations (at least) have seen for themselves how antisocial it can get, as people flout the official “advice” of social distancing, and continue to go to parks, bars, and city streets. It’s true in the UK, in the Netherlands, in the US and Canada… and even in Italy, which has become the epicenter of the virus in Europe, and famously overwhelmed by cases such that they’ve become a cautionary tale. It becomes apparent that people whose realities depend on individual freedom are ill-suited to self-regulate, while the extreme population movement control measures in China, impossible to even think of implementing in a democracy, have begun to lead to positive results.

We are left with something of a “ice hockey player dilemma”: individually, people want to do what they want to do, and they don’t want to be the sucker who follows the doctor’s advice when everyone else is out having fun, but if everyone were required to conform to the same rules, there’s less tension to be resolved. That means to rely on action through social obligation alone is insufficient; it is also necessary to enforce from a policy level. As Frank argues in Under the Influence, to reduce antisocial behavior, both by persons and organizations, it must be seen as costly.

Whether speaking of the immediate, and hopefully short-lived, concern of coronavirus, or the long-term problem of climate change, the ultimate outcome may be found in a question in the book, posed by David Wallace-Wells: “The question of how bad things will get is not actually a test of the science; it is a bet on human activity. How much will we do to stall disaster, and how quickly?”

Under the Influence: Putting Peer Pressure to Work by Robert H. Frank is available from publisher Princeton University Press.

Under the Influence: Putting Peer Pressure to Work by Robert H. Frank is available from publisher Princeton University Press.