"If you care about giving communities stability and a chance to keep themselves safe and produce a civic life, then housing is a big part of that story."—Matthew Desmond, in our interview about his book Evicted.

A Determination to Co-Produce: An Interview with Anthony Luvera

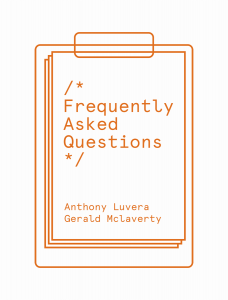

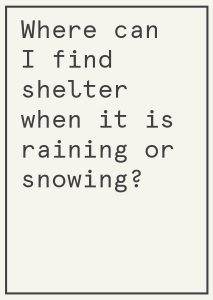

If you were homeless, where would you sleep during the night that is safe? Where would you go to the toilet at night? Where would you wash your clothes, and where would you go to use a computer? These are some of the questions about access to basic human necessities posed in the book Frequently Asked Questions, co-produced by Anthony Luvera and Gerald Mclaverty. Beyond the questions, however, this is also a book of the responses—and lack thereof—from the local government offices of the UK responsible for homelessness. Mclaverty, who has himself experienced several years on the street, and Luvera, an Australian artist based in London, formulated and refined the questions over several years, based on the desire to offer real and practical answers to the matter of active homelessness. After sending these questions out to local governments, however, they realized the answers they hoped for were not forthcoming. Luvera speaks in this interview about the evolution of his work with people experiencing homelessness, his practice of socially-engaged co-productive projects, and the dynamics of collaborating with people in vulnerable situations.

If you were homeless, where would you sleep during the night that is safe? Where would you go to the toilet at night? Where would you wash your clothes, and where would you go to use a computer? These are some of the questions about access to basic human necessities posed in the book Frequently Asked Questions, co-produced by Anthony Luvera and Gerald Mclaverty. Beyond the questions, however, this is also a book of the responses—and lack thereof—from the local government offices of the UK responsible for homelessness. Mclaverty, who has himself experienced several years on the street, and Luvera, an Australian artist based in London, formulated and refined the questions over several years, based on the desire to offer real and practical answers to the matter of active homelessness. After sending these questions out to local governments, however, they realized the answers they hoped for were not forthcoming. Luvera speaks in this interview about the evolution of his work with people experiencing homelessness, his practice of socially-engaged co-productive projects, and the dynamics of collaborating with people in vulnerable situations.

I want to start with what I see as the most impactful part of this book: it is comprised of charts and email text and data. It is in one sense incredibly dry material, and yet, that’s also what gives it such emotional power, which is a really interesting contrast. What’s the story behind the Frequently Asked Questions?

In 2013-14, I was working on a large project called Assembly, with people experiencing homelessness in Brighton. In our plans for putting an exhibition together, as part of the Brighton Photo Fringe Festival, I was keen to include in the gallery space information about support and services available around the UK for people experiencing homelessness, or at risk of experiencing homelessness. I worked with a research assistant who was also a residential support manager for the Brighton Housing Trust, the homelessness support service that I was working within, and we gathered a lot of information from a range of charities and local authorities, and pulled it all together. It was really striking how general the information was, and how it seemed to serve a purpose of marketing for the organization, rather than actually providing practical answers. So, I struck up a collaboration with Gerald Mclaverty to come about gathering this information in a different sort of way.

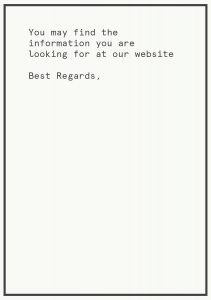

We sent out an email to 44 local authorities, the largest by population around the UK and all of the local authorities in London, asking a simple set of questions written from the experience of someone experiencing homelessness—from Gerald’s point of view. We thought we’d get lots of really useful information sent back to us that we could then put into the gallery space, but what we got was a bunch of auto-replies, where very rarely do they follow-up or answer or honor their timeframe pledge. And that seemed to say as much about the state of legislated support services for people experiencing homelessness than anything else. So, we put together printouts of the initial emails and all the correspondence into a kind of dossier on clipboards and put them into the gallery space on tables for people to consider. That was the first iteration of Frequently Asked Questions.

The book is effectively the project’s third iteration, right? After sending out questions again in 2017 and 2019?

Yes. A few years after that, in 2017, I struck up a relationship with the Museum of Homelessness, which is a really interesting model for a cultural organization. It doesn’t have a physical premises, but it operates within the frameworks of other cultural institutions, as well as doing a lot of lobbying and direct action to provide support and services around homelessness. They were planning to put together an exhibition in the Tate Liverpool and offered to platform the work, so Gerry and I got back together and thought about to how to further develop the Frequently Asked Questions project. We decided to expand the number of local authorities for the email, and then to spend time analyzing the responses.

We wanted to present the work on a 13-meter wall, so I hired a graphic designer, Will Brady, to help with that side of things. Gerry and I discussed with Will that we wanted to use the architecture and the interface of online communication to inform the design decisions, to tell the story of sending out these emails, as well as providing a way for audiences to better understand how their local authority performed.

The show at the Tate Liverpool was in January 2018. A little later that year, the Homelessness Reduction Act came into effect, which placed greater duties on local authorities to provide care for people experiencing homelessness or at risk of homelessness, and was the first major piece of legislation related to homelessness in around 15 years. So, a year after that, in 2019, Gerry and I thought it would be a really good time to revisit the project, and we sent out another round of emails. We designed the show that was exhibited at the People’s Republic of Stokes Croft at the end of 2019, and at The Gallery at Foyles in London in January 2020, as well as the book.

The show at the Tate Liverpool was in January 2018. A little later that year, the Homelessness Reduction Act came into effect, which placed greater duties on local authorities to provide care for people experiencing homelessness or at risk of homelessness, and was the first major piece of legislation related to homelessness in around 15 years. So, a year after that, in 2019, Gerry and I thought it would be a really good time to revisit the project, and we sent out another round of emails. We designed the show that was exhibited at the People’s Republic of Stokes Croft at the end of 2019, and at The Gallery at Foyles in London in January 2020, as well as the book.

I think you’re right, at the heart of the presentation of this work there is a kind of disjuncture, or a friction, between this bureaucratic process and the emotional punch of understanding that there’s an individual in the middle of it all, who is trying to understand, to receive answers, and to receive support about their rights to access—the kind of basic living conditions that we all take for granted.

How does the collaboration with Gerry work?

In the three iterations of Frequently Asked Questions, Gerry and I made decisions together—around where to send the emails to, what kind of questions to ask, and the visual identity of the exhibitions, posters, and book. We meet periodically at the public library in Brighton, and throughout the pandemic we have continued to talk on the phone. Gerry has access to email, and we regularly communicate with each other through email as well.

Also, it’s important to mention, a big part of this project is not just the information that it presents in the exhibitions and book, but is the program of public events designed to activate and animate this information. Gerry has a say in this side of the project as well, both in terms of the planning of the events and attending and contributing to them when he can. Gerry has been an extraordinary collaborator. As someone who’s experienced homelessness, he feels very strongly about it. The systems and services in place, purportedly to help, often can’t or don’t, because of the way that they’re constituted or enacted. Often, when I’m invited to speak publicly about the work, I’ll invite Gerry along. When we were invited to speak at an event at Tate Modern, Gerry came along and addressed the audience, as well. When he’s not able to come along and take part in events, he has created audio recordings that I can use.

So, he’s very much a co-creator in this project. I mean, the whole idea of authorship is interesting when it comes to socially-engaged or collaborative practices, because there’s an expression of agency that an artist has, which is very different to a participant. And I’m really aware of that power imbalance, so I want to open up the decision-making process as much as I possibly can with Gerry.

What are the public events you mentioned?

At the Tate Liverpool, for instance, there was a program of events that included a practical workshop with a collective of activists, Established Beyond, about how to squat commercial properties; a panel discussion with Liverpool Salon involving academics and CEOs of local homelessness support services; a film screening with local activists; creative workshops; and a performance in the exhibition by The Choir With No Name, a choir of people experiencing homelessness. At the exhibition in Bristol, the events program included a two-day creative response workshop with IC Visual Lab and Rachel Kiddey, a collaborative archaeologist, as well as a reflective space hosted by the Museum of Homelessness for the Dying Homeless Project for people to come together to remember and commemorate individuals who had died whilst experiencing homelessness. At The Gallery at Foyles, there was a day of talks with more than 18 speakers working in a range of fields in relation to homelessness, including participatory theater, legal representation, employment services support, psychology, nursing, history, literature, as well as people experiencing homelessness, that were all brought together to consider the different kinds of creative tactics we can use to shake up preconceptions of homelessness and lobby for housing justice.

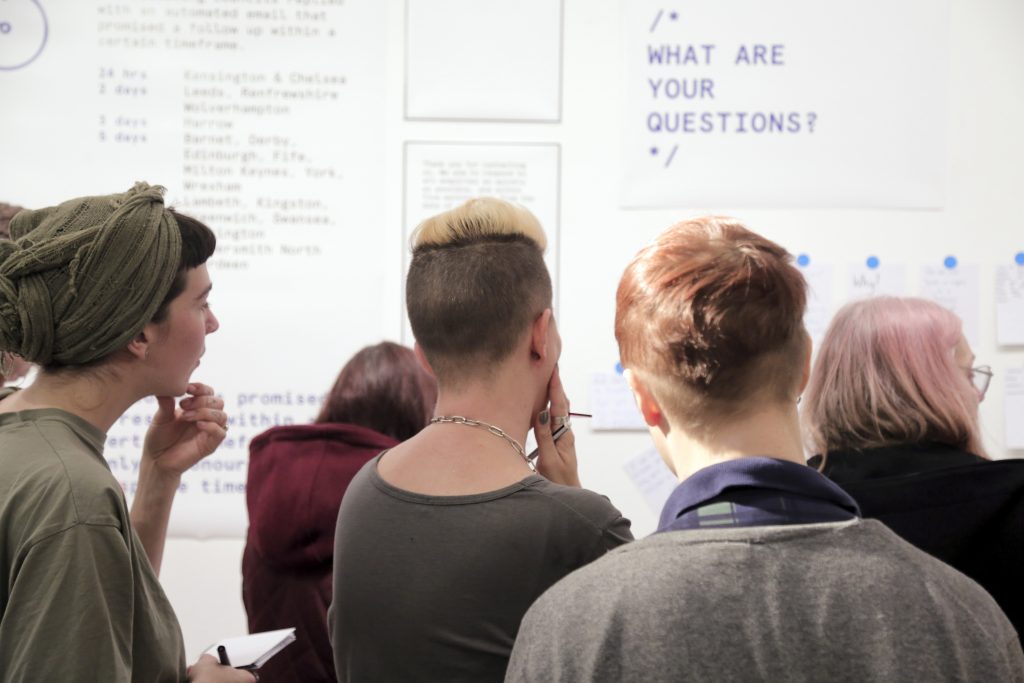

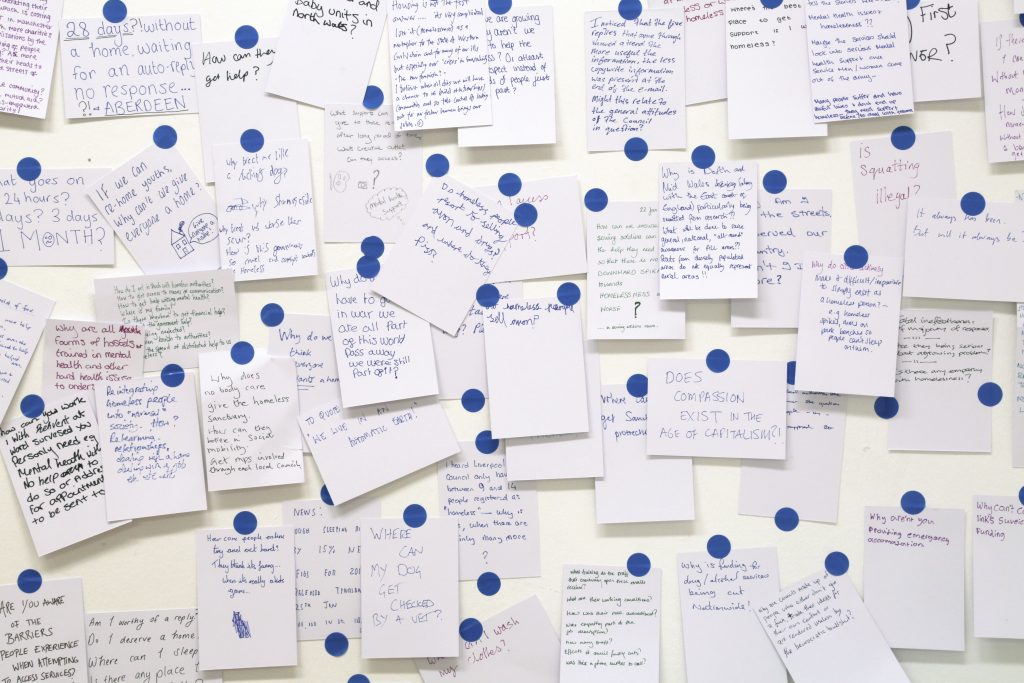

So, for me, Frequently Asked Questions is as much a presentation of data as it is about finding ways of engaging multiple audiences in different ways to consider the information. Also, the exhibition of the work in the gallery space always has a section called, “What are your questions?” where the audience can suggest further questions or share responses, that get folded into the life of the work.

I’m glad you mention the audience; social issues tend to be niche and I want to ask you if your intention is to reach a wider audience to raise awareness or if it’s mainly to speak to those who are already primed to take action on the topic of homelessness?

I’ve always thought of audience in the plural sense for this work, so when putting up exhibitions, I’m really interested in finding spaces that have an adjacent role to the art world. For example, the show in Bristol was at the People’s Republic of Stokes Croft, which is an activist-run community center. They have an existing audience, who may certainly be more familiar with and engaged with the kind of social issues that homelessness is a consequence of, and it’s also relevant that the space doesn’t function as a white cube gallery space. So, there isn’t that sense of exclusion that a gallery can sometimes have. Or, take the Foyles exhibition—Foyles is a five-story bookshop in central London, which has a public gallery on the top floor. There are approximately 30,000 visitors a week who come through that space. It’s really interesting for a gallery because it’s a mix of public and public space, and the people who come into a bookstore are potentially already geared towards thinking about ideas and to want to read and spend time considering information. So, the choice of location is one that I’m consciously thinking about, to be able to subvert the normative behavior expected of the function of an artwork in relation to the audience, and to shake up the expectations of how audiences should behave in an art gallery. And, of course, when it comes to the public engagement events, each of those is designed to bring in a different type of audience.

With the publication itself, the primary audience are MPs, councillors, and people working in the homelessness support sector. The first distribution of the publication was a mailing sent out to around 300 people working in positions of power at the local and national level, who have a stake in decisions that are made in relation to homelessness. The response from people working in support services and at a grassroots-level was really encouraging, both in terms of the work affirming what they already know, but also because it disrupted their expectations, as well.

There is—and I mean this in a good way—surprisingly little of you in this publication. That is, you’re an accomplished photographer and especially portraitist, but none of that is on display here. How do you see this as an expression of your work?

You’re right, my long-standing practice as an artist or photographer has been about making images and distributing those images. Frequently Asked Questions came out of my photographic practice, but the progression of this project really has been determined out of a sense that it uncovers information that needs to be seen, shared, understood, and acted upon. A practice of creating images can only go so far in terms of communicating specific information and pointing out the structural circumstances that contribute to the experience of homelessness. So, it certainly was, in one sense, a departure from my practice but in another sense, it’s just a new evolution because at the heart of my photographic practice has always been co-production—a determination to co-produce with participants. I want to build opportunities for dialogue between myself and participants, and also, between the work and audiences.

As artists, as photographers, we’re storytellers, and for me, Frequently Asked Questions is a story that needs to be told.

Let’s speak about what you just said—your determination to co-produce. Why has that been so important to your practice?

My work with people experiencing homelessness came out of an invitation by someone working for homelessness charity called Crisis, almost 20 years ago, back in 2002. It was a well-meaning invitation to go to a large shelter for people experiencing homelessness over the Christmas period to photograph them. But I felt very uneasy about doing this. At that time, as I continue to be, I was very interested in the politics of representation. The critiques of documentary photography representation—I’m thinking of work by artists such as Martha Rosler and Allan Sekula, and writers like A.D. Coleman and Abigail Solomon-Godeau—suggest that if you’re involved in image production, then you need to be really mindful of how you’re treating the people you’re representing, and how you use the contexts in which to communicate that representation or the images you create. Rosler uses the term, “representational responsibility”, which has always stuck with me.

So, after I turned down that original invitation, I was doing some consultation work for Kodak on their disposable cameras, and I found myself in a position of being able to access a large number of single-use cameras and processing vouchers. I went back to Crisis and said that I’d like to see what the people I’d meet would photograph. What I learned was the people I was working with were the best-equipped people to be able to communicate their points of view, their experiences, and the things they’re interested in. And this really sparked my interest in participation, collaboration and co-production. It’s been a quest ever since to find new ways of doing this, and in doing so, to consider the kinds of questions it raises, the problems it poses, and the opportunities it may bring about.

There’s certainly no shortage of horrifying work that demonstrates a complete absence of representational responsibility, so it’s clear that good intentions aren’t enough—though it’s certainly a good start. How do you think an artist should challenge themselves to be sure they’re being mindful? What are the questions that you ask yourself to make sure you’re staying mindful?

Generally, when I am creating a new project, and particularly when I’m working with people experiencing homelessness, I’m really keen to develop a relationship with a support service that has a toolkit of specialisms to be able to support individuals. To give you an example, I’ve been working on a new project with people experiencing homelessness in Birmingham since 2018, commissioned by a photography organization called GRAIN in collaboration with a support service called SIFA Fireside, which is the main day centre for homeless and vulnerably housed adults in Birmingham. I spent over a year getting to know the staff of the organization and the people accessing the services there, by going in and spending time working in the kitchen, serving food, volunteering on the floor of the social space, and simply spending time getting to know people. For me, this process of getting to know people is not only about establishing relationships and developing trust, but it’s also a process of asking questions. So, before I even bring in camera equipment, I’m spending time to ask questions about whether or not I should even be there. Is this something that would be useful? If so, when—what sort of day? How long should it take? Where in the building? Are there particular individuals that would be good to speak to about this idea? Getting this sort of feedback helps me shape decisions about carrying out the work.

More broadly speaking, the questions I tend to ask myself are: What gives me the right to be able to do this? And, what gives me the right to be able to go about it in the way that I expect to go about it? Is this the best way to use photography to tell this particular story? Should I be the person pointing the camera and pressing the shutter at that individual? For me, I’m more interested to ask how can I involve or invite the participant to understand the implications of representation, to understand how the use of equipment will have an impact on how they’re depicted.

There’s a really good question, which I often borrow, by the American critic Patricia C. Phillips: Does it succeed because good intentions are irreproachable? I think that’s one of the best questions, particularly in relation to work that is socially engaged, participatory or collaborative.

What’s your impression of homelessness services in the UK beyond the charts and data you present? You’ve been collecting responses now three times since 2014—has much changed or progressed?

The thing that we noticed in the 2019 iteration, which we hadn’t seen before, was a few local authorities invited Gerry for a meeting or a phone call. I think that is a direct response from the piece of legislation that took effect in 2018, the Homelessness Reduction Act.

Although this book has the presentation of a quantitative data project, and there is a lot of quantitative data in here, which is really useful and valuable, I think the qualitative analysis is most telling. For instance, in 2019, one of the local authorities counts in the charts as having responded to the questions. From a quantitative perspective, you might think, “Oh, good job, they answered the questions, they’re responsive and providing answers,” but when you read the actual responses, they’re outrageously cynical.

Although this book has the presentation of a quantitative data project, and there is a lot of quantitative data in here, which is really useful and valuable, I think the qualitative analysis is most telling. For instance, in 2019, one of the local authorities counts in the charts as having responded to the questions. From a quantitative perspective, you might think, “Oh, good job, they answered the questions, they’re responsive and providing answers,” but when you read the actual responses, they’re outrageously cynical.

The value of Frequently Asked Questions is, for me, less about charting the performance of an individual local authority, than it is pointing out the structural makeup of support services for homelessness, and how the very fabric of that is, in some senses, the problem here.

Indeed, some of the auto-responses that you include seem to be standard boilerplate; things like “We’ll get back to you within 24 hours or within 10 working days at the latest.” If I got that response from a business contact or customer support, it would be completely normal. Yet, in the context of someone sleeping on the street who’s trying to get basic information, those hours and days are critical time to not be lost in bureaucracy. The seeming obliviousness is callous if not cruel. What does this say about the friction between the individual and the institution?

Institutions are made up of people, and people enact their mechanisms. So, at some point, someone turned auto-reply on, and drafted the response to go out to people who had written to that particular email address with their queries about homelessness and housing. Someone within the organization is cognitively making those sort of decisions within this framework that we call the institution.

One of the things that I think Frequently Asked Questions demonstrates, is each local authority has its own operational procedures. From a practical perspective, there’s learning to be exchanged between local authorities about how they operate. From another perspective, it also points out that each local authority, however they respond, is essentially enacting a philosophy of care. When you send out mass communications or messaging in a particular kind of way, that’s demonstrating a particular kind of duty of care. What needs to be uppermost in anyone’s mind that works in the framework of an organization that is communicating with people at risk of homelessness, or experiencing homelessness, is how not only responsive they need to be in terms of timeframe, but also the quality of information they provide by tailoring of information to the individual query—just the human-ness of actually replying.

That’s the thing, really. It’s a demonstration of care, or lack thereof.

Have you seen any direct change or consequence take place following the presentation of this material and sending the book out to those 300-odd decision makers and power holders?

The representative from Exeter city council made contact after receiving the book. They expressed in their communication that they had always felt that Exeter city council had done a good job of providing support and services for people experiencing homelessness, but that this project had prompted them to really take into consideration the experience of the individual on the receiving end of that information. She spoke in her email and on the telephone to me about how the work has prompted a much broader discussion within the city council with different departmental heads about how to rethink the ways in which that they deal with people experiencing homelessness.

The MP [Member of Parliament] for Cities of London and Westminster, Nickie Aiken, reached out to me and invited me to meet with her online to hear more about the project, in regard to her particular local authority and how it deals with people that are rough sleeping. It was really good to have an opportunity to be share that information with her, and hopefully that will impact the kinds of decisions that she then makes.

Gerry and I were invited into the Houses of Parliament to meet with Neil Coyle, who’s an MP for Southwark in South London, but also the chair of something called the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Ending Homelessness, and alongside some colleagues and other people working in support services, we presented our work to them.

So, although this project has been going since 2014 and there’s been three iterations, for me, this feels like a very early stage of the project. Gerry and I have spoken about producing subsequent iterations and after the pandemic begins to settle down here in Britain, we’ll be thinking about issuing the next Frequently Asked Questions, because the homeless support service or sector has had such a shake up throughout this time. It will be really interesting to see how it rebuilds itself, and in doing so, how it takes on the perspective of people experiencing homelessness in the decisions that it takes.

When you talk about taking on that responsibility, in terms of having conversations with MPs and representatives, this starts to sound less like an artist’s work, and more like the job of a consultant or lobbyist or activist. How do you see that as a socially-engaged practitioner? Where do you feel your responsibility begins and ends?

I see it as work that I’m engaged with, that doesn’t appear before a public. That work of reaching out to MPs or councillors, following up those lines of communication, finding opportunities to put this information onto their desk, and to suggest that they share that information with their colleagues—this is a vital part of my practice as a socially-engaged artist. It kind of loops back to that question you asked earlier about audiences. Had I chosen to only show this work in a gallery space, even a public gallery space, it would have felt like a missed opportunity for the work, and the wrong spending of effort.

Look, photography doesn’t need to just appear in publications, websites, and gallery walls. It appears everywhere. It’s part of the fabric of our lives. But I’m just not interested in making “visually stimulating images” of people—the images obviously should be visually stimulated, but I’m far more interested in what more they can do.

On this notion of activism, I primarily identify as an artist or photographer, and as an educator and writer. I’ve never called myself an activist, even though perhaps this work is taking me into the territory. But I work alongside and in consultation with people who really are activists, and when I see the lengths that they go to for the work they do, I think that this pales in comparison, or at least, it does something different.

I share your uncertainty about what the boundaries of that are. Certainly the notion of being an “artist-activist” has its own problems since, as we talked about earlier, a lot of harm can be done under cover of good intentions.

Using photography to point out societal issues needs to go further than just “show-and-tell.” In some ways, what Frequently Asked Questions showed me was that images could only take me so far, in speaking out about the systemic problems that cause homelessness. So, I’ve had to just follow that through. It felt like I’d been told something that was too important not to share, and had I just put it down and not followed it through, then it would have been just the wrong thing to do.

Yes, and for an artist, the success of spreading a project brings its own conflicts. That is, when you work on a social topic and try to get the word out, it might be that you benefit more from that than the issue itself. It raises some really confronting questions like, how do you know if you’re really good, or just acting good as some kind of virtue signalling? Sometimes it’s clearly one or the other, but I get the feeling that other times it’s impossible to say.

I’m aware that as an artist, what I do enables me to build cultural capital. Working with particular institutions opens up further opportunities for me to be able to access resources and audiences—I’m aware of that and that’s part of being an artist.

At the same time, with a project like Frequently Asked Questions, the primary audience is people working in local authorities, the support sector, and parliament. When I push this information, it’s not for any display of cultural capital, but to enable me to put this information in front of people who have the decision-making power.

I just think we can be more expansive about what a photographer is. It’s not always that the photographer needs to be in control of the shutter. For me, in my broader practice, I’m really interested in the techniques used in forum theater to generate participative discussions and the notion of critical consciousness. I’m also interested in the visual research methods used in ethnography and other forms of the social science disciplines. I’m thinking critically about ideas coming out of radical education, about deconstructing the power dynamic between the educator and the student. So, my broader practice of photography is a kind of sublimation of all these different ideas and ways of working with representation, and Frequently Asked Questions is just the next iteration of this really. It sits within but also extends my practice of working with photography.

What’s the most important thing you’ve learned when it comes to making socially-engaged projects?

Well, one of the most valuable lessons that I learned was when I was putting up an exhibition of Assisted Self-Portraits and photographs created by participants in 2005 on the London Underground, as part of the Art on the Underground public art program. I did as much as I thought I possibly could with the participants to inform them about the exhibition: I took prototypes of the posters into the workshop space to discuss with participants, I invited participants to come with me to the exact locations of the billboards and the advertising holdings where their pictures will be shown, I asked people to sign consent forms.

Still, when the exhibition went up, one of the participants was very unhappy. She did not like it, and she wanted images of her removed immediately. So, I got in contact with the curator, and we had them taken down straight away. And then a few weeks later, the participant changed her mind and asked for the work to be put back up, but unfortunately by that stage we didn’t have the resources to be able to do this.

What this all showed me was that consent is a process and it’s a dialogue. Just because someone says “yes,” it doesn’t mean they’re precluded from the capacity to say “no,” later. And to say “yes,” again. But this dialogue is what consent is, really.

You know, when I first began working with people experiencing homelessness around 2002, with the disposable camera project, I had no idea that nearly twenty years later, I’d still be working with people experiencing homelessness. It’s the relationships with people that have held me to it, really. I think about someone like Phil Robinson, who I worked with back in 2003-4 to develop the methodology to create Assisted Self-Portraits. Now, he is housed, he works as a photographer, and he’s always out with his camera. I often see Phil photographing at demonstrations and rallies, and he’s always posting on Instagram. And, I think about Jeff Hubbard, who was a participant in the early years of my work at Crisis with people experiencing homelessness. After I left, he has continued to run the photography workshop at Crisis. Relationships with people are key, and ultimately this is what drives my work forward.

See more from artist Anthony Luvera on his website