"Because it was about a state of mind, I knew that it was something that was going to have me throwing myself against the limits of representation. Translating emotionality and personal experiences into a picture is always going to be hard. "—Katrin Koenning, in our interview about her photography.

Boys Who May One Day Be Monsters: An Interview with Elizabeth Clark Libert

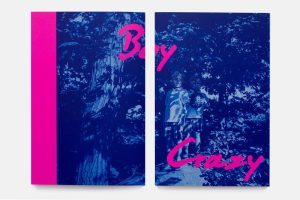

In her photographic monograph Boy Crazy, artist Elizabeth Clark Libert addresses an uncomfortable gendered position: How should she, a heterosexual woman who has enjoyed and endured the attention of men, raise her young boys, who will eventually become men?

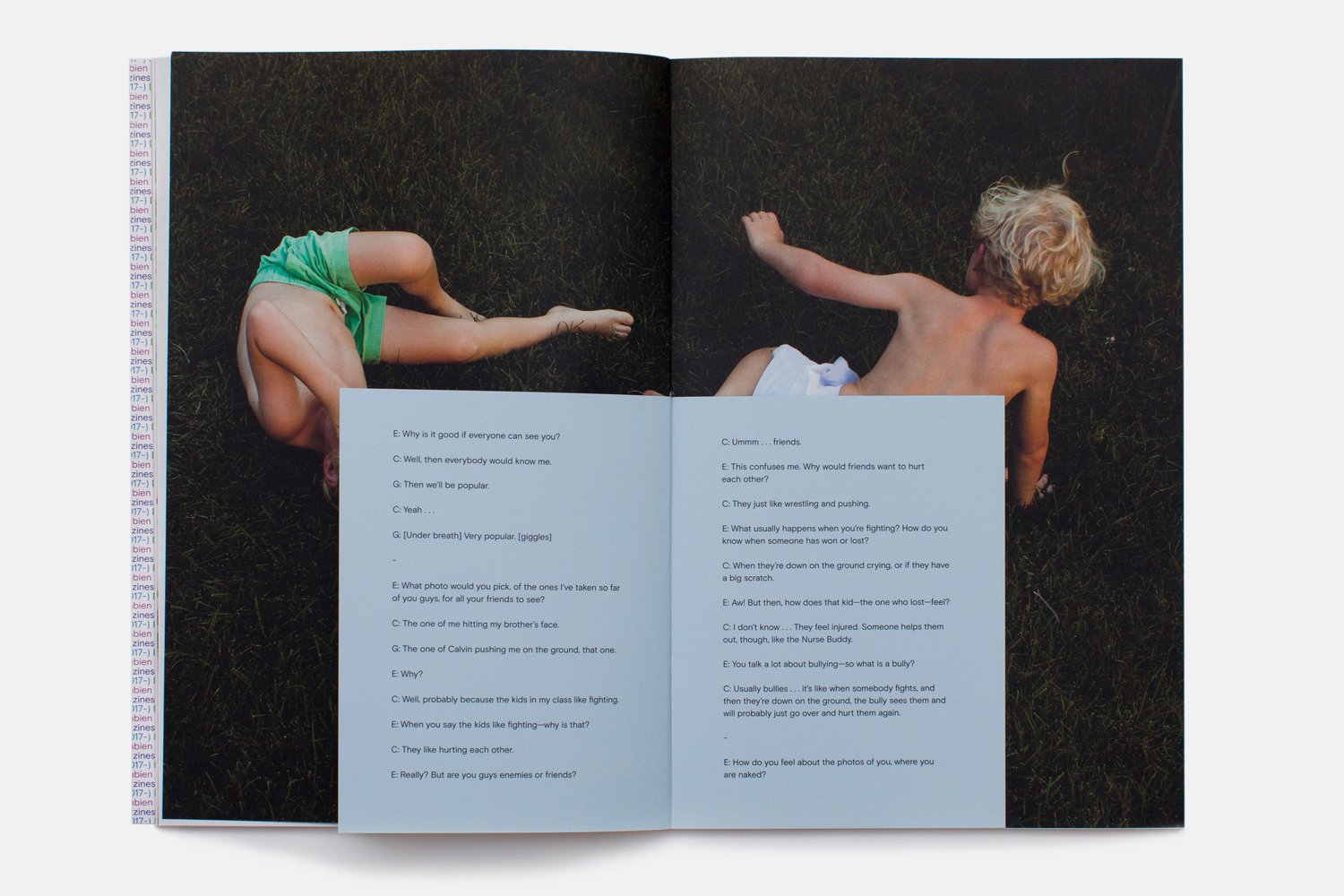

Libert’s attention to this question is deeply personal. In written texts, she unearths stories from her youth on cultivating and capitalizing on the male gaze, and shares gut-wrenching tales of traumatic interactions with a college classmate who stole and distributed nude photos of her, and another young man who raped her. She replays these events, dissecting her experience and its aftermath in a phenomenological portrayal of trauma, which she then interweaves with contemporary conversations with her young sons, and photographs of their boyhood innocence.

The book is a masterwork of gendered relations, speaking to love, desire, hurt and healing. We speak in this interview about processing trauma through art, the importance of making people uncomfortable, and reconciling with shame.

Your book portrays a question of how to raise your sons, who remind you of the boys from your own coming-of-age, but the book is steeped in a history of hurt and there’s an underlying sense of unresolved trauma. So, here we are talking in an interview, but I find myself in a strange position of not wanting to ask you to delve into things. So, where do we begin?

Your book portrays a question of how to raise your sons, who remind you of the boys from your own coming-of-age, but the book is steeped in a history of hurt and there’s an underlying sense of unresolved trauma. So, here we are talking in an interview, but I find myself in a strange position of not wanting to ask you to delve into things. So, where do we begin?

People will ask me, “Has the process of making this book been healing?” and I’ve definitely come to realize that every time I discuss the book, I re-expose myself to pain. But I’ve developed language that helps me navigate it. They say that if you can name the emotion you’re experiencing, that can make the feeling more tolerable, or you feel more confidence sitting with it. I’ve found that to be true. For such a long time, I would just feel pure shame. Now, I’ve slowly gotten to a place of being able to look at that space. Like, I’ve been able to experience the anger, the rage—both at myself, and also at the perpetrators. And I’ve been able to understand that the rage at myself and the shame were not so accurately placed.

So, I do feel like the process of both making and talking about the book, and the trauma therein, has continually helped me get to a more empowered place. It’s given me more tools. I used to get so emotionally overwhelmed that I just couldn’t deal with it, so I’d bury it – “gag it down”, so to speak – and move on. This process has been transformative.

I appreciate that you don’t want to have me re-encounter the trauma, but I believe, at the end of the day, it does me more good than bad to be able to talk about and move through it all.

What’s the “good” that it gives you?

Ultimately, I think the book encourages awareness and conversations about consent. Also, it encourages other people who have had experiences with trauma to be able to process and deal with complex emotions like shame.

One example is the mom group at my kids’ school. They wanted to support me, so many of them ordered a copy of the book. I let them know it was quite heavy material, dealing with trauma, but even with that warning, I think some of them were really shocked. But many of them reached out to me to say, “I’ve experienced similar things and I want to talk to you about it.” Solidarity is a good word. To know that friends want to talk. It was especially important in that particular group because we all have sons. This is a parental concern that we share.

The hardest part of putting the work out there is not so much having the public read it or having conversations like this one with other people in the art world, it’s more the conversations with the people closest to me. My family members, my mother, and especially my sons. They’re not yet at the age where they’d understand the work fully, but they’ve seen some of the images and ask questions, like, “Why are our faces crossed out?”

Let’s talk about the difference between the story as your reality and the story as it’s been aestheticized into a “work.” How did you approach the process of transforming events into work?

When I started this project, I didn’t have any anticipation of the final results or a flushed-out concept. It simply began with photographing my sons. I was, however, very aware that I was creating these images that contained metaphors of lost innocence or taken innocence. I was also looking at my sons and questioning their nature—whether they had that potential to become cruel. To be evil. It’s one of my biggest fears.

I don’t tend to believe in absolutisms, by the way—I think people make mistakes. But when I began to consider these questions and fears as a parent, I was asking myself if they’ll be able to acknowledge their mistakes.

I wanted to elevate the work and make it into a book, though, so I reached out to a designer that I admired, Caleb Cain Marcus. I liked his collaborative approach and that he created books with other photographers that felt like an art object. Caleb encouraged me to reach out to editor Jonathan Blaustein. Then we became a pretty good team. Jonathan was the one who pushed me to think more about the why. I kept saying that I was photographing my kids because I’m worried about them becoming monsters, and he was like, “But why? You’re going to need to give the context of that.”

I didn’t want to. I didn’t want to get into the specifics of my memories, I thought I could just hint at them. At that point, JB encouraged me to write, and that’s what opened up the floodgates.

I realized then that I had a choice: I could go the route of creating something that exposes the depths and messy emotions that I was dealing with and make a clearer statement for an audience, or I could keep it more subtle and poetic and suggestive. I decided to lean in.

There’s definitely more risk to exposing yourself. There are plenty of careless editors or publishers who would be more than happy to squeeze people’s trauma out of them for the salaciousness and the scandal appeal. How did you arrive at that choice to know going deep was the right thing to do?

I decided to give myself the freedom to write in this state of “no constraint”. Well, to be honest, I don’t remember even giving myself permission to do that, but once I started, that was where it went. I couldn’t stop. Clearly it was stuff that I needed to get out. Once the memories were down on paper, I could reflect and understand how that period of my life affected how I was seeing my sons and projecting my own trauma onto them.

I decided to give myself the freedom to write in this state of “no constraint”. Well, to be honest, I don’t remember even giving myself permission to do that, but once I started, that was where it went. I couldn’t stop. Clearly it was stuff that I needed to get out. Once the memories were down on paper, I could reflect and understand how that period of my life affected how I was seeing my sons and projecting my own trauma onto them.

From there, I could be more conscious about how much I was willing to expose and how much to pull back. So the editing process began. Ultimately, I liked the juxtaposition of my raw voice to the dreamy, suggestive images. I wanted to relay the story in a language that was accurate but also artistic.

I also became aware of the concerning parallel between my experience of having my own nude photographs stolen from me, and some of the nude photographs of my sons that I was capturing. I wanted this parallel to be apparent, but I also had to figure out a way to give them agency, as best as I could, while I was simultaneously reclaiming my own.

Some of my family members and my husband looked at drafts and encouraged me to pull back on some of the writings – they want to protect me of course – but I think it became super important to me to get past the shame of what happened. I didn’t do this myself. This was done. This happened to me.

At some point, I found the conviction to bare all.

You’ve just touched on something that I want to get into: your husband. There are these notable absences in the book, in the sense that you don’t mention your husband or your father. Is that a deliberate narrative choice, or more of a personal choice?

A little bit of both. I wrote several vignettes about the relationship with my husband, and ultimately I decided that they were too distracting from the narrative arc. It would’ve taken things off-track, the book would’ve had to be bigger and even broader than it was. I wanted to keep a tight edit.

But you make a good observation. Sometimes absence, or negative space, holds a certain type of information.

I suppose the reason I ask is because, throughout the book, there’s the running question of how you, as a mother, can raise your sons to not be monsters, but I’m wondering about the limitations of that. Is it possible that some lessons can only come from other men?

Probably. I guess I still wrestle with the concern that the book ultimately discredits my husband. That said, the process of making the work has generated questions which led to some difficult conversations that I really needed to have with him. I think he needed to have those conversations with me, too, but perhaps I hadn’t allowed him to know these things, as I had partially shielded my past.

There are currently a lot of conversations in public discourse about gender and the sexes, and this is quite plainly a very gender-focused book. How are these external events shaping what you see and what you bring into the work?

There’s so much going on! One of the initial reasons I started this project, like I write about in the book, is that triggering moment where I see my son’s face and it’s interrupted by a vision of one of the perpetrators—he looks a lot like my son. That was at a time when Trump had been in his first presidency for a couple years. The #MeToo movement has been going on for a couple years at that point, too. We were starting to have a lot of cultural discussion about toxic masculinity and white privilege. My sons were passing their toddler years, and were now engaged in more rough-and-tumble and stereotypically gendered “boy activities”, and I was a little shocked by it all. All those cultural events were coalescing with my personal experiences.

I am currently reading a book called BoyMom, by Ruth Whippman, and she brings up many of the same questions that I, too, am concerned with. I’m not 100% in agreement with everything that she says but, on the whole, I worry about boys. I just do. Women are surpassing men in so many areas. Is that why men are acting out? What is their place in a future world that is less labor-focused? How does society deal with male rage? How do we help them? How do we protect ourselves? Why does it seem like this is our burden as women? As mothers?

Have you gotten any feedback or reactions in general from men about this work?

Not so much, no. I received emails from some male family members, but on the whole, I’ve noticed that men are much more uncomfortable with it. I guess they aren’t the audience for it, which I admit frustrates me.

My husband, for example, was uncomfortable. My editor Jonathan, when it came to the question of what to include, would admit reading certain vignettes made him uncomfortable. When I started to hear this feedback I became even more determined. I thought: It’s a problem that this makes you uncomfortable. (As my sons would say, “This is an ish-ue, not an ish-me”!)

I don’t mean to imply anything bad about either of them admitting discomfort! I was grateful that they told me they were uncomfortable. I know there’s going to be a lot of people who struggle when they start to feel emotions like shame or confusion. That’s a good thing.

Do you feel like there’s any risk of this experience gaining undue weight in the story of your life by transforming it into a book?

Within my own little world, I tend not to dwell on it too much. But yes, that might be a good motivator to keep making new work. Like you said, I don’t want this experience of trauma to define me. But as an object of art, I’m very proud of this book.

One of my biggest concerns is how my sons will understand it. My strategy is to use it as a jumping-off point to discuss tough topics like consent, incrementally, at their level. As an impactful, parental tool for difficult discussions. In time, I hope they’ll understand nuance and have the ability to talk about hard things.

Let’s talk about how “forgiveness” plays a role in this work for you.

There are two senses of forgiveness that I think about in this work: Do I forgive these perpetrators? And, do I forgive myself? There’s been a lot of self-loathing and a deep-set belief that I was partially at fault. In terms of the perpetrators, I tend to assume that they have issues of their own. What did they go through to make them do that to me? And they were drunk, so what role does that play? To what extent do we escape ourselves and who we are and our sense of responsibility while under the influence of alcohol and drugs?

Some of this convoluted inner dialogue plays out in my writing, which I think is some of the most disturbing – and sad – parts of the work, and of the experience. I’m much quicker to turn towards inner-anger, and acceptance and forgiveness of others, as opposed to forgiveness of the self. Self-blame, I guess.

It sounds to me what you’re describing is not forgiveness, but letting someone off the hook. Does that resonate?

That’s a good point. I wonder if forgiveness requires an apology. When you forgive yourself, it’s almost like an act of forgiveness, right? It’s a moment in which you acknowledge the fault and actively commit to letting it go. When it’s for another person, do they need to acknowledge the fault? What do you think?

I think forgiveness has to at least acknowledge the wrongdoing – even if that just happens in your own mind, rather than coming from the other person – whereas letting someone off the hook abdicates responsibility. It hands them an excuse that says it wasn’t even wrong, in a way.

I agree. You can forgive someone without having to give that person knowledge that you’re forgiving them. That’s probably a better way to approach it, if you indeed do decide to grant it.

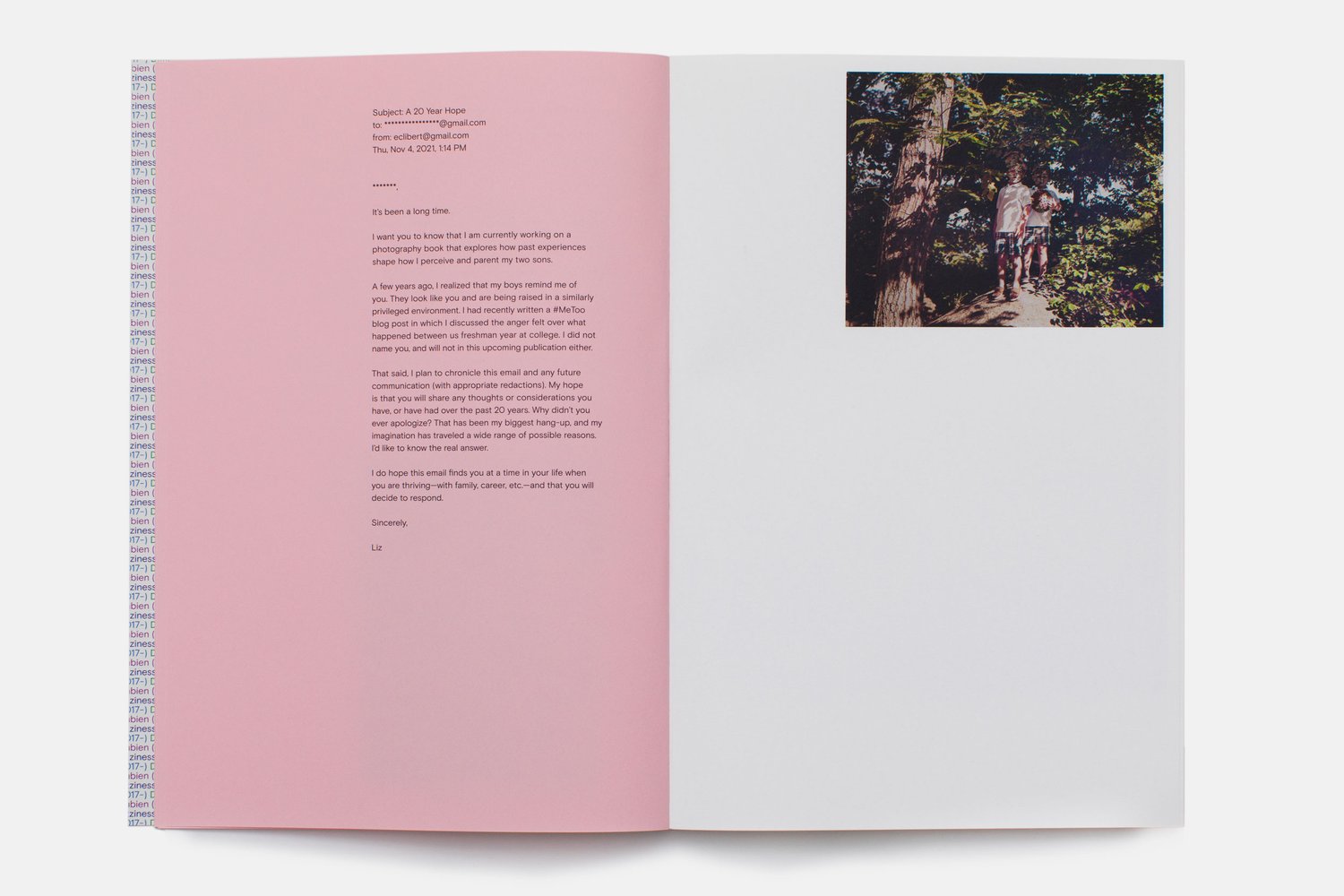

In the book, you document a conversation with one of the perpetrators that you hope will be healing in some way but ends up being rather unsatisfying. I kept thinking about the expression: Not everyone who hurts you cares.

Yeah, I definitely felt that way. I had to take a step back and ask myself, “What am I looking for out of this?” Part of it was the act of confronting him and asking the question of why, even if there was no chance of getting a satisfactory response. There was something empowering in finally having him have to bear witness to my question of it and having to think about it, even if it wasn’t necessarily on the level that I wanted.

I think the bigger moment of growth for myself was revisiting my younger self and saying, “This wasn’t your fault.” I was, in essence, mothering myself. It’s such a simple statement, but continues to be tricky for me to wholly believe. But, at least, I’m now at a point where I can see what that means: perspective, patience, understanding, and ultimately love. This work helped all of that to blossom.

How do you think the work helped achieve that? Was it the process, thinking about the work, talking about the work or editing the work?

I honestly feel lucky because, again, I didn’t set out to make this work with the mission for it to be therapeutic. It occurred organically, step-by-step. An awareness would hit me that I’ve got shit I need to deal with here, and then again here, now. I wasn’t even able to name the self-loathing and shame until after the book was published. I was still grappling with fear.

Even when I confront the perpetrator – that’s obviously a big turning point in the narrative – the decision to reach out was, I admit, partially strategic. In addition to wanting to know the “why?” so badly, I knew the story would benefit. But then, because of the unsatisfactory way in which the conversation played out, that led to the next step of asking, “what do I need to do for myself to feel better about this?”. And so I wrote, and included, my conflicted emotions regarding the conversation. There were all these steps of growth, of deeper understanding, little by little, along the way.

It has let me take the story back and make it my own. Creating the work on my terms has been a practice of becoming more resilient. I’m now at a place where I’m feeling quite proud about it all. The journey. We’ll see, because there are times when I still feel doubt, but I think doubt in a creative context is just good common sense.

Boy Crazy is available from publisher Workshop Arts. See more of Elizabeth Clark Libert’s work on her website.