Ancient maps marked the accomplishments of discoverers, documenting the world as known thus far, the…

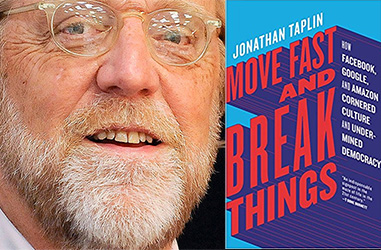

The Intensity of Exposure Featuring the photography of Øistein Sæthren Dahle

The thing about being born a human is that none of us get out alive. Some of us spend our whole lives ignoring that fact, taking time like it’s on infinite tap, while others act according to their fear of death, as though certain cautious steps and right decisions could lead to a reprieve. Somewhere in between these two extremes is the harmony of death exhaling from, and inhaling into, life.

In this manner, life and love seem to me interchangeable, and it is all too common to want the rose without the thorn. We seem to think we can get the great guiding light of humanity without the trouble of all that dark.

Or, the other way around, in a toxic entanglement of emotion some are convinced that pain is proof of love.

How are we to understand, let alone live with, the comingling forces of contrast? Are these opposites even essential? In The Wisdom of Insecurity, philosopher Alan Watts argues: “Because consciousness must involve both pleasure and pain, to strive for pleasure to the exclusion of pain is, in effect, to strive for the loss of consciousness. Because such a loss is in principle the same as death, this means that the more we struggle for life (as pleasure), the more we are actually killing what we love.” This sentiment is echoed by contemporary researcher Brené Brown when she says, “You cannot selectively numb emotion.”

Consciousness is, in a sense, contrast. It seems to be essential to our being that we experience some negative aspects of existence so that we may better understand and orient ourselves towards the positive—should we choose to. Poetics can so easily shape struggle as a necessary component of victory that many will, shy of understanding the victory that they actually seek, orient themselves merely toward ongoing strife and suffering. It speaks to the extent that we as humans need a sense of purpose that we are more willing to fight for nothing than we are to stare into the void of meaninglessness.

Consciousness is, in a sense, contrast. It seems to be essential to our being that we experience some negative aspects of existence so that we may better understand and orient ourselves towards the positive—should we choose to. Poetics can so easily shape struggle as a necessary component of victory that many will, shy of understanding the victory that they actually seek, orient themselves merely toward ongoing strife and suffering. It speaks to the extent that we as humans need a sense of purpose that we are more willing to fight for nothing than we are to stare into the void of meaninglessness.

It takes a brave and resourceful soul to fight for oneself.

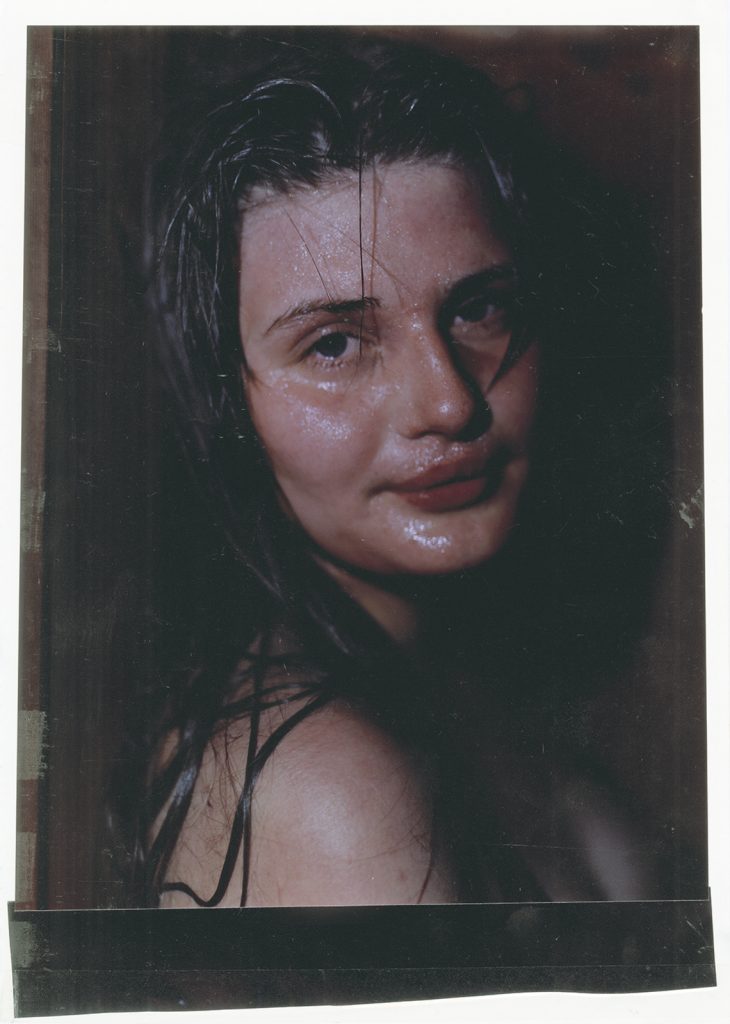

When it comes to love, the threat is existential. We repel from a black hole of loneliness on one side, and another of absorption on the other. The magnetism of belonging, acceptance and love draws us close, before we pull away with equal force to reclaim ourselves. To make love is the perfect fractal metaphor: our bodies seek to blur their boundaries, to conjoin, and yet, the very pleasure that we receive from the act is based on our separateness. We open ourselves up to others with the hope of feeling this ecstatic tension, and are sometimes crushed by the sorrow of unmet affection or the deep disorientation of loss of self.

Most of us only figure out how to live under threat of death, and we only learn to love at the cost of being profoundly alone. “To love means to commit oneself without guarantee, to give oneself completely in the hope that our love will produce love in the loved person,” writes Erich Fromm in The Art of Loving. “Love is an act of faith, and whoever is of little faith is also of little love.”

Most of us only figure out how to live under threat of death, and we only learn to love at the cost of being profoundly alone. “To love means to commit oneself without guarantee, to give oneself completely in the hope that our love will produce love in the loved person,” writes Erich Fromm in The Art of Loving. “Love is an act of faith, and whoever is of little faith is also of little love.”

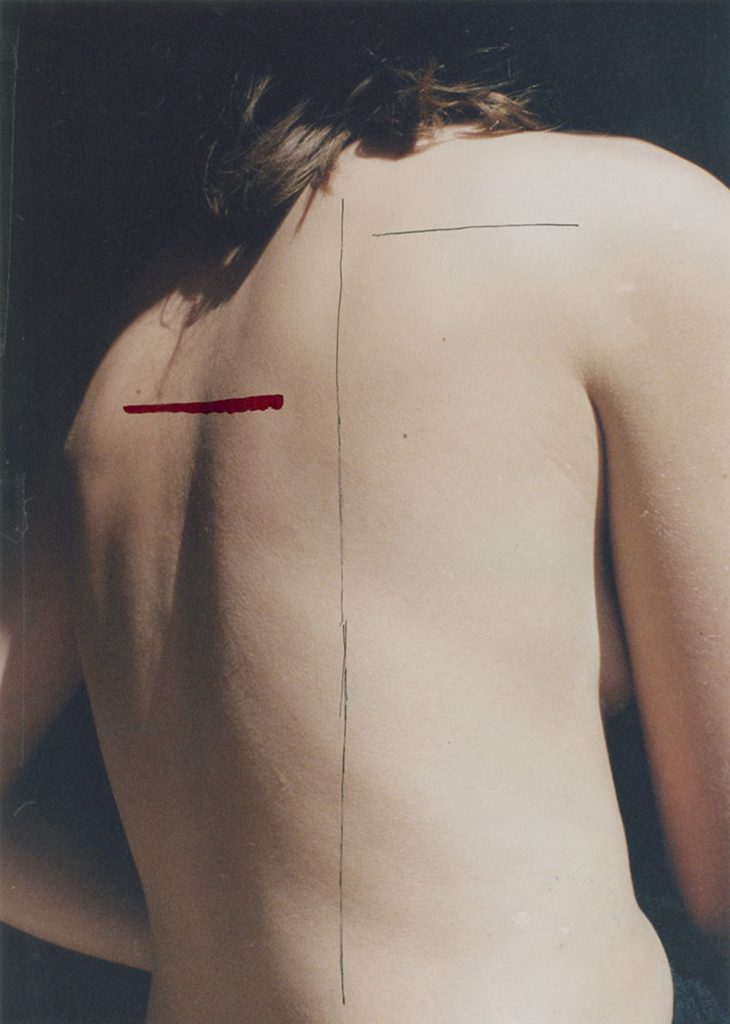

In this, we are connected, and each of us must choose the terms under which we are willing to exhibit great acts of faith at great personal risk. This is not a one-time negotiation, but one we must undertake again and again, with each round offering dear prizes, and hellish punishments, to our gentle, mortal hearts. Over time, the intensity of this exposure takes its toll on our flesh.

We will not survive our lives, though we can ensure that we choose our days and our heartbreaks well. As we open our hearts we must also open our eyes, so that when we encounter others, we can see better their faith.

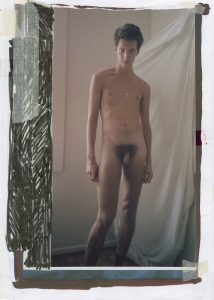

Love Kills My Words is a project by Norwegian photographer Øistein Sæthren Dahle (1988). He began photographing his series in 2009, during a period when he was beginning a relationship and also a close friend had died. Sæthren Dahle brings the images together into a sketchbook with drawings, contact prints, annotations and hand-drawn flourishes, fueling the feeling of phenomenological expression. It is planned for publication from Kodoji.