"There’s a lot of people who don’t understand that art is something that’s woven into the fabric of the community to strengthen it. What I’m doing is feeding, or nurturing the community’s souls. Helping spirits who need it."—Lake Montgomery, in our interview about singing-songwriting

Creativity on Demand: An Interview with Dina Litovsky

Dina Litovsky (b. 1979, Ukraine) is a New York-based freelance photographer, who has carved her career at the intersection of art and editorial. Her documentarian’s viewpoint is distinctively stylish, bringing a vibrantly colorful palette and vital playfulness to unexpected areas of society, like the Amish vacationing in Florida, Santa Clauses lounging by the pool en masse, and urban bachelorette parties, among others. Since 2021, she has been writing a newsletter about her “adventures in the unseen world of photography,” In the Flash, which peels back the curtain on matters both practical and personal about being a contemporary working photographer. She recently wrote about the difficulty of consistently creating on demand, and the looming burnout as an overextended freelancer. In this interview, we speak further on the risk and reward of the freelancer lifestyle, and how she’s built a career doing what she loves.

When I read your article Being Burned Out and the Tightrope of Creativity, it immediately spoke to me for multiple reasons. First, because also I’m a freelance creator, so I was able to recognize some of the demands of needing to take a job even when I don’t have the bandwidth for it, and second, because it was so refreshing to see someone writing so openly about their experience of it. To kick off, I want to ask you about the emotion that you describe feeling about photography when things are going well: the “giddy excitement.” Tell me more.

I guess everybody feels that way when they’re doing something they love—you know, the things that you don’t do for money, just for yourself. It feels like the most exciting thing ever. I don’t know how to describe it better than “giddy excitement,” as I can spend nights awake and happy and thinking about the project I am working on.

I only get into something when I feel this particular way. If I don’t, it’s a very easy telltale sign. With photography, especially in the beginning when things started working out, like the first time I did a project or the first time I won some major award, I remember those moments. I felt just like a conqueror. Victorious. It was just the best feeling in the world, like the folly of youth and optimism.

Have you always been a photographer, or did you start out with other careers that you can contrast this against?

It was my first real career, but I only picked up my first camera at 23 and I only went to school for photography at 30. Before that, I was going to be a doctor (my mom really wanted me to become one), and I did an NYU psychology degree and pre-med. I’ve had random jobs like working in a law and medical offices. I got fired from every job because I just stopped going. I was the most horrible worker; I’d just not show up one day and get the last paycheck in the mail. At 23, I could not hold a job and the idea of working in a corporate environment sounded horrendous.

Photography was my first real career and I picked it up mostly because I hated everything else. I had no particular “love” with photography when I started. My family wasn’t into photography—they didn’t know anything about it—but I used to paint and draw, and I also have a background in art history. So, I was into arts, but not photography. Then my parents gave me a camera (they regretted that for some time), and things suddenly and very quickly started working out. It’s an amazing feeling when you pick up something and discover you’re good at it. It was like that. I wasn’t great, but I was good. So, I went from not being interested in photography to realizing it could be my ideal profession. And very quickly, people started paying me for it. I remember my first photo shoot, for a girl who needed her picture for a dating website, and she paid me $40 for taking her photo. It was the best money I ever earned. I thought, “Oh my god, this is amazing. I can make money doing this!” That was how it started. It was almost a fluke, I would say.

You were describing how negatively you feel about “work.” Does photography feel like work?

Rarely. There are things in photography that I don’t want to do, and there are assignments that I don’t love, or times when I have to stay up all night working, but it never feels like “work” in terms of being bored. I’m never bored—I’m challenged. And, yes, sometimes I’m frustrated, and sometimes I feel like I hate everything, but it never felt like that other work, where I didn’t feel like myself.

So, photography feels like work, but it never felt like work that’s bad. It’s the same as what I hear from other people who enjoy what they do.

At this point, you’ve published and exhibited widely, you’ve won various prizes that acknowledge your work, and yet you still talk about the challenge of photography, as well as experience the struggles of freelance work. How would you describe where you are now, in terms of your career with photography?

I’m writing about photography. Facebook hired me to write for their new newsletter platform, Bulletin, and for the next couple of years I will be writing for my photography newsletter, In the Flash, as pretty much a full-time job. I realized recently it’s the first real job I’ve ever had: I have to write five articles a month, which is a lot for someone who is not a writer, so I have to wake up and write, no matter how I feel. And when I don’t write I read as much as I can to improve my writing. This now takes most of my bandwidth.

It started to go this direction, though, because I actually got to a point with photography where I’ve stopped learning, or at least, the progress has really slowed down. I found that I can do some assignments with my eyes closed and still make good work. It somehow plateaued, and usually when I plateau at something, I quit, or I restructure what I’m doing. So, then writing came along, and I had to start from scratch. I’m thinking about photography, though, and that’s actually added to my practice, because I’m thinking through things that used to be just vague concepts. Now, when I write it down, I’m finally able to see: “Oh, that’s what I meant by this picture!” This better informs what I can do in the future.

So, I’m writing right now, and it’s really exciting because I’m often failing. It can be excruciatingly hard, but that’s what I like. I’m learning how to be a better writer and that’s exciting. It’s also making me more excited about photography, because it reveals things that I couldn’t get with the camera alone. With photography I thought I reached something of a dead end, and now, I feel like I’m going through this to the other side.

What comes on the other side of this dead-end, do you think?

I’m not a planner, so I can’t think about it long-term. I don’t plan beyond my next dinner. I know what things give me joy at the moment.

I am looking forward to photographing for as long as it’s not boring, and a lot of learning and experimenting and play is involved. Right now, I’m concentrating on writing, but I don’t have a long-term plan. I don’t see myself doing something outside of photography though—I don’t know how to do anything else. So, it’s not like I have a choice.

Well, in your article, you did mention wondering if it was too late to be become a chef or a mixologist. It seems like you have some choices available…

Yes, I thought about it, but it’s too late for that now. That’s even harder than photography. It’s not realistic at this point. I just turned 42 in December. If I wanted to become a chef, I would have to restart from scratch. Let’s say I go to culinary school. That’s another five to ten years. I don’t have it in me, to do that.

Writing is nice because I’m writing about my photography, so it’s not completely starting over. I’m adding to the practice. I’m interested in doing more with photography than photography, I’m interested in being more reflective on the culture of the medium. Something that’s not just a visual output, but that’s more thoughtful and relevant to the culture at large. There’s a lot of room for that in photography.

Considering how much of your photographic practice revolved around observing people, how did the pandemic and lockdown affect you?

The beginning was really tough. I thought that I wasn’t going to work again until it’s over, because everything that I love to photograph was gone—just dead. My jobs dried up overnight. I went from flying everywhere, every two weeks, to just having no jobs. That was very stressful.

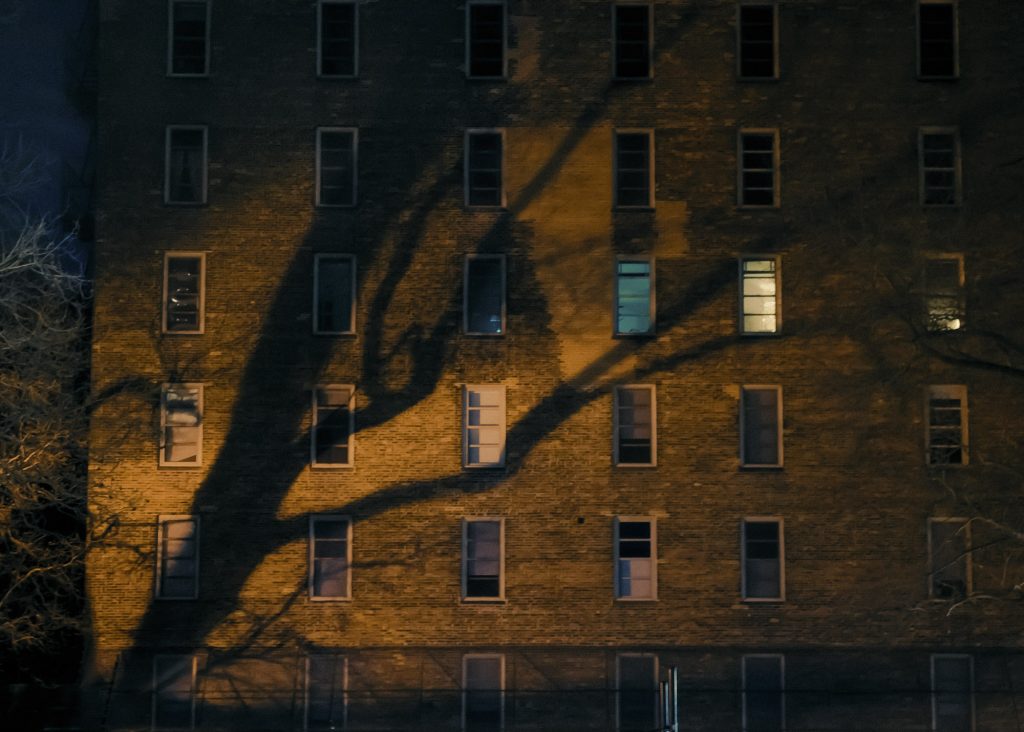

I had to reframe the way I’m photographing. The Dark City project that I did was a direct result of that type of burnout, where for the first month, I was just flailing around and complaining to my husband that I’m done as a photographer. Then, at some point, I got tired of whining and hearing myself whine, and I just looked at what can be done under this set of circumstances. I started photographing silence, for example. I mean, it completely changed the way I was working pre-pandemic. I only used to photograph group behavior and general chaos. But suddenly, what seemed at first to be a creative crisis turned into a creative opportunity to do new things and try new options.

Given that you had time to reflect in a way that you ordinarily didn’t, what emerged from that?

Mainly that there are a lot more options with photography other than editorial work. When it comes to editorial, no matter how successful you get, it’s not a guarantee that you’re going to be working in a year. It doesn’t matter who you are. Maybe an editor quits, or someone changes their mind, or you go out of fashion, and you lose all the jobs. Being a photographer is not like being a lawyer or doctor, where you work for something for years and then you’re set. The result is almost the opposite: You work, you work, you work, and then people get bored of you. And, you know, that was kind of always a fear.

With the pandemic, I opened up new possibilities that don’t rely on editorial assignments. That’s no longer my prime income, it’s more like I’m doing them for fun. Now, I have more freedom to write, or to teach, I can give back more to people and have a conversation versus just producing output. That’s refreshing.

We’ll see how long that lasts. I’m a pessimistic optimist. Like, I enjoy things, and I’m optimistic and hopeful… but how long is that going to last? I always anticipate how things will end.

I love that. (laughs) Let’s talk about being creative on demand. From a practical perspective, how do you handle that constraint?

I realized that being a good photographer is not just taking a good picture—that’s how it seemed in the beginning. It’s much more about being able to produce work on demand. Taking a good picture is easy when inspiration strikes you, when you’re in the mood. When I started working editorial, there were a lot of assignments that I failed because I didn’t give it 100% and I thought I could get away with it. But the pictures showed it, and it took me years to realize that this job isn’t like other jobs, where you can sometimes get away with excuses. Here you can’t. It doesn’t matter if I am sick, or if I had an argument or I’m depressed. It just doesn’t matter. People look at the final picture, and nobody cares about the backstory. It was a very hard lesson to learn, because I love excuses.

I have to be creative on demand, because, again, if I mess up an assignment then I’m probably not going to get a callback. That editor, or that publication, is not going to hire me again. And that is a very stark reality of photography, right? You have to be at your optimal all the time.

Being creative… It’s an exciting thing, right? It’s usually thought of as some kind of a sparkly gift. But when you have to do it on demand, it’s completely different. There have been times when I was doing back-to-back assignments for weeks. It took a lot of practice to be able to do that. That’s when I really considered myself a professional, that I learned how to do that well. I learned to completely refocus my mind, and to have everything else recede in the background and just focus on the images—that took years.

Before that point, what would you do when you felt like you couldn’t create on demand?

Mostly panic.

Did that help?

No… I messed up a few assignments, and then got to see what happened when I messed those up. I was disappointed in myself, and I never got the jobs back from the mags and publications. It was a very hard reality to see that. You do great at your first ten assignments, and you mess up just one—and the editors stop working with you.

So, yeah, at first, my reaction was just panic. I don’t have any specific tips how to get over it. I am very resilient in general, so I can panic, but then there’s always a point where I get tired of myself panicking, and I find a way out.

When you talk about focusing your mind for the job at hand, Is that a conscious act of focusing, or is it more like turning your brain off and letting it happen? What’s going on?

I think it’s a little bit of both. I feel like now I can do it automatically. There have been times when I’ve had a fever, or I’m in a bad mood, and all of it would go away because my body refocuses somehow and that happens automatically. Once I have a camera in my hand it’s like I’m a guided missile, everything just drains out, and I’m focused, and I feel better. My adrenaline kicks in. I don’t know how it happens, that’s subconscious. For that brief time that I’m photographing, I feel better and I am able to produce work, even in very, very stressful situations. It took at least a decade of practice to get there, though.

Do you feel that way about photography in general, or are there parts of your work that give you energy and other parts that take your energy?

Pretty much everything about it gives me energy in a way.

Wow… that’s love.

It’s exciting! I mean, I’m a very opinionated person, and this is one way to get my opinion out in a way that’s not didactic or overbearing. I just really enjoy being able to formulate all the thoughts in my head through my photographs. It gives me some kind of understanding of the world that is very satisfying. It indulges my curiosity. I find the whole process of photographing fulfilling: the research before is satisfying because I get to learn things, and I love editing – I love editing! – because it’s like discovering little presents.

The only thing that’s draining is the way the industry is organized. The fact that there’s no security. People can just decide not to work with you at any moment. It’s very trend-based, so once I become older, let’s say, and people want to work with new photographers, then what am I going to do? I feel less concerned about that now, I guess, because I see other outlets, but that has been a big concern when I had only editorial work. That was always draining, the lack of security. There’s no steady paycheck every month, it can be a lot of money one month, and then two months of nothing.

That’s worth digging into, because you’re not just creating on demand, you’re doing it as a freelancer. So on top of the industry insecurity, there’s also the personal insecurity. When it comes to the risk versus reward aspect of freelancing, where do you stand?

I mean, I would still choose to be a freelancer. I still get to choose the jobs to a point and make my own schedule. I’m just not good at constraints. I’m not good at waking up early, for example, so one of the reasons I chose photography is because I can sleep in most of the time! Of course, now that I’m older I wake up at, like, 8:30 by myself anyway, which is ridiculous. But the freedom to set my own schedule is important.

Obviously, the negative is the complete lack of security. Again, you never know when that next job is going to be. And there were times when I would have ten jobs in a row, being so busy that I actually had to say no to some, and then I had two months of nothing. And you feel kind of helpless, because you have no control over it.

It can also be a problem that you so easily get pigeonholed, so even when you’d like to do other assignments, you’re not able to control which assignments you get. That’s stressful. For years, I tried very hard to get out of being pigeonholed as a party photographer. It took five years to get out of that. At some point, I was doing only parties, and even though I used to love that, the time came when I never wanted to see another party again for the rest of my life. Of course, now that I’m not shooting them, I miss parties.

When you talk about the freedom that you want out of your work, what’s most important to you? I tend to think of two types of freedom: There’s freedom from certain things, like freedom from a fixed schedule or freedom from a boss, or freedom to, like freedom to choose or freedom to leave when you want. What do you need?

Freedom to sleep? I don’t know, you’re asking tough questions! I just like making my own schedule and deciding what I’m working on, versus being made to work on things. Right now, for example, for the first time in my life, I’m in a position where I can choose what not to photograph. I’ve actually been saying no to assignments that I didn’t want to do. That’s just been happening the last year, and I would not have been able to do that even two years ago. I said yes to everything—even some that I didn’t want to do at all. But, you know, you suck it up because it’s money and you never know when it’s coming. The first time I said no to an assignment, it was intoxicating. So, that feels like freedom to me.

Yes, I know what you’re talking about. I started freelancing with the idea that I wanted to be able to choose my jobs, but then, at the beginning, I was so busy trying to earn a living, I couldn’t say no to anything. So, it filled me with a lot of doubt that I was doing the right thing. What am I really getting here? It’s only after I was able to say no, that it started to feel something like that freedom.

How long did it take you?

Any day now… No, I’m kidding. But in all seriousness, at least several years.

Yeah, that seems to be a good amount of time. Some people never get there at all. You know, the freelance world is scary. I feel like it’s even scarier for writers. I know a lot of writers and they’re always talking about the lack of security and not knowing when the next story is going to come. And these are really successful writers—published writers who work at big magazines and write cover stories.

I think writing and photography have a lot in common in that sense. They both seem to be industries that require a certain amount of starting wealth to be able to get anywhere.

For a long time, I was doing weddings. There are a lot of lucrative things you can do with photography that the art world won’t even consider, but weddings pay a lot of money. So, you can make money in photography, as long as you don’t expect to be making whatever kind of photography that you want to do. Take the type of photography that we consider as “documentary,” or what’s suitable for magazines. The pay doesn’t even compare. What you earn for a one-day wedding compares to what you earn for a full week-long magazine assignment. When I found that out, I was shocked. I was doing weddings for ten years, and I put myself through school with it. I could support myself, yet people would look down at it because weddings are considered to be the ‘blue collar’ work of photography. The people at art school said that I shouldn’t do weddings or, at least, to not tell anybody. Then, at some point, they were asking if I need an assistant because that MFA was expensive!

So, you can make money with photography if you make it commercial. It’s just you can’t do everything, you can’t do it all. Eventually, I stopped doing wedding photography, and that was a victory for me, when I realized it was my last wedding. That only happened around five years ago. Before that, just financially, I couldn’t stop.

You’re still managing to combine your editorial work alongside your personal work. How does that work? How does your personal work fit into what you’re trying to do with photography overall?

My personal work is my main work. For editorial work, sometimes they coincide, which is great. I like editorial because it opens doors for me that I would never be able to open by myself. So, I take editorial work not just for money, but to learn and to get access to something new. After all, I never know where my next idea is going to come from. But it’s all leading toward my personal work. That’s really what gives me the most joy.

I’m continuously working on projects, though, so it becomes very interlinked. Like, my personal project Meatpacking, which I got published in Time and a lot of magazines. So, even though it’s personal work, it starts earning itself back later. Other times, the editorial assignment leads to the personal work. It’s a very, very close intersection of the two. It’s almost the same at some point, depending on the assignments, obviously.

You’ve been described as a “visual sociologist.” What does that mean to you? What drives you as a creator?

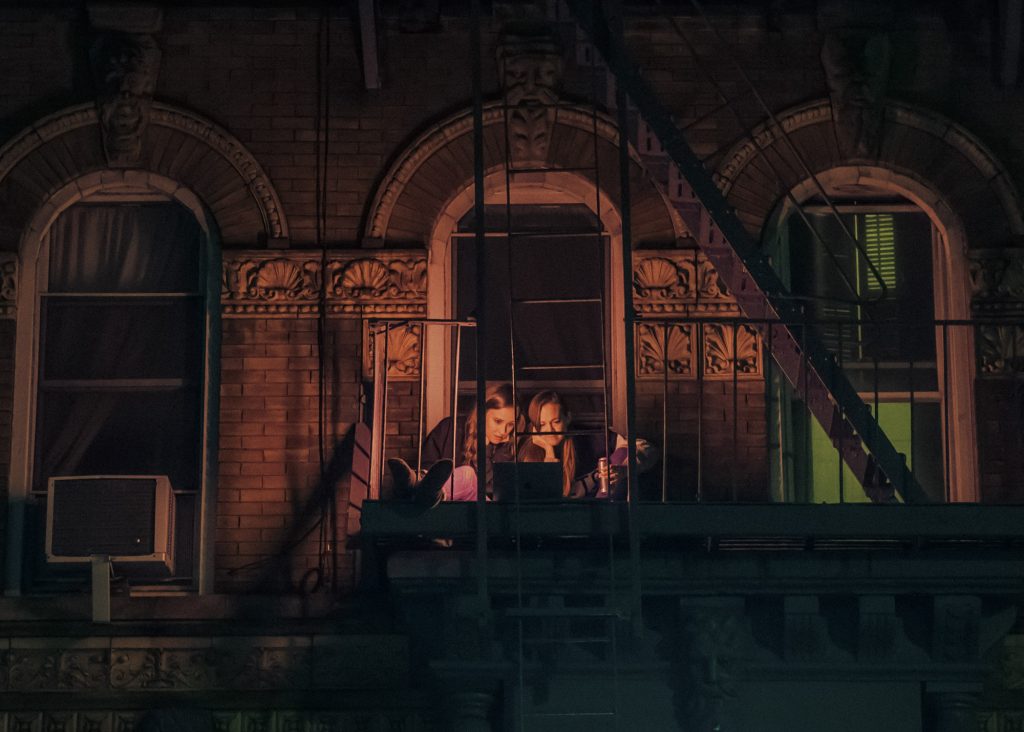

I’m observing human behavior, it’s as simple as that. What drives me is that I used to have fairly bad social phobia. I was not participating in any social activities—like, I never went to prom, I hardly went to parties and when I did I would sit in the corner and look at everybody having fun. Having a camera helped to make it go away, because with the camera I have a purpose to be there. I don’t have to interact with people. Not to mention, I feel unnoticed. When people see a camera, they see their own reflection.

I was always curious about human behavior, but unable to be as close as I wanted. So, I started going to parties with a camera, because it gave me a reason to be there. It’s like a passport to do what I always wanted.

So, that’s why I like to observe: I’m very curious about people but I’m afraid of them at the same time. I haven’t had social phobia for a while, and I feel that’s really because of the camera. I’m still unable to go to a party without a camera.

That’s especially interesting considering you studied psychology, but you don’t think of yourself as a psychologist with the camera, but a sociologist with the camera.

Psychology is more about inner worlds and yourself. I’m more interested in how people interact with the environment, how people interact with other people, and the broader culture. I’m less interested in individuals. That’s why I’m more interested in documentary than portraits. People interest me more as a broad spectrum, rather than as individuals.

What’s currently making you curious about people?

I’m just curious. I’m interested in how the culture is shifting. All of a sudden, I feel like I’m of a “different generation.” For example, I just wrote an article about consent for the newsletter, which went a bit viral. Basically, there’s a change in perception about documentary photography that I’ve been seeing over the last few years, which is that people now say that you need consent to photograph on the street. I’ve noticed that when I publish my images on NatGeo, for example, more and more people chime in with, “Did you have consent?” This wasn’t a conversation even three years ago.

I feel that it’s a little too easy for a non-photographer to say something like this about consent. Consent sounds like a good thing. I mean, what can be wrong with consent, you know? I didn’t see many people willing to argue that we shouldn’t ask consent because that sounds really bad. But, if you think it through, it doesn’t make sense in street photography.

So, I was looking at the shift in behavior, where people see someone with a camera all of a sudden as more of a creep. Like, a man with a camera is always seen as a predator. I’m seeing this shift in attitudes towards the camera, and that really got me thinking. Do I adjust? Do I want to adjust? What do I do, as a street photographer?

This really illustrates what you said earlier about having time to be reflective about your photography and what images mean. Bringing it back to the topic of being burned out, what place does burnout hold in your creative process? What do you think it’s doing for you?

It tells me when I need to take a second and stop. Usually, when that happens, I’m unable to become creative on demand. There’s a point where I just can’t. The brain shuts off and there’s nothing I can do about it. Usually, that’s kind of a sign for me to simply stop, whether it means to take a vacation or just to not take a job, even though I really want to, because I’m not going to do well on it. And that’s hard to do, but I’ve learned to listen to that.

It’s hard. It’s harder than it sounds. Because if I don’t do things—a lot of things at once—I feel like I am slowly dying. I always have to be doing something. But, again, it’s not a good thing. Sometimes I need to make myself just sit on a couch and sit with my cats and stare at a wall. That’s a really good practice, to just do nothing—not watch TV, not read, but just stop. That’s been the hardest thing to learn.

Are you still feeling burned out, or is that particular episode over?

It never lasts long. When I wrote that article, I was already getting over it. I was complaining about how I was feeling and my husband said, “Why don’t you write about it?” I wouldn’t have been able to write about it when I’m the middle of it, because I’m just not functioning. I spent a week already of being not functional. And then writing about it really helped, because I was able for the first time to enunciate it instead of just feeling a big black anxiety. Putting into words what I was going through made me feel much better.

What triggered the burnout for you?

I think it’s more that something is accumulating. It depends on the jobs, and if there are too many things that I’m doing just for the money, let’s say, versus out of love. I don’t mind working a lot if I do something that I love. I mean, I don’t get tired. It’s something different when there are things that I don’t want to do.

Are there other things you’ve seen over the years that affect your ability to create on demand?

There are a lot of dead ends, where I feel like I’m not doing as well as I want to. For example, I struggle with portraits. I never feel like I can take the portrait as I have it in my head. I’ve tried to educate myself on portraits, reading about them and looking at photography books, but I feel like there’s some kind of a natural dead end about being a portrait photographer. Sometimes I take a good one, but it’s always more of a fluke than a deliberate thing. And that’s been frustrating. It’s frustrating when I can’t do things that I want to do. So, recently I wrote a post about portrait photography and thinking that through helped me to understand it much better.

I also tried to do more conceptual work, let’s say, to move away from photojournalism and documentary, but that’s very hard to reframe. I find myself trying, but it’s like having a wall in front of me. So, I go back to my comfortable way of doing documentary. That’s a constant struggle, you know? It’s always two steps forward, three steps back. That’s a real ongoing internal struggle, that I want to get better at certain things, and I can’t. It’s frustrating.

What does it mean to you to be “successful”?

Oh, that’s a hard one. Everything that comes to mind is such a cliche.

Let’s say this: I feel very lucky with the job because I get to do what I love. It never feels like a job for me. I’m simply happy to be here. That makes me feel successful. Not because I’ve been published in magazines—of course that doesn’t hurt, it feels good. But it’s more that I am doing things that I enjoy, and I’m actually getting paid for them. Am I getting paid well? That’s another story, but I don’t have to scramble anymore, as I used to.

I never expected to be financially secure with photography, I just thought that somehow, I’d survive. Now, for the first time in my life, I am financially independent. And again, this literally happened two years ago. It took a while, but to be able to feel that way with photography is great thing. So, right now, this is good. This is a good place. That feels like success to me.

See more photographic work from Dina Litovsky on her website, and read more in her ongoing newsletter In The Flash.